Little Caesar

By Marv Goldberg

© 2019 by Marv Goldberg

There were several singers who called themselves "Little Caesar". The two most famous were Harry Caesar (the subject of this article) and Carl Burnett, lead singer with Little Caesar & the Romans. There were also Little Caesar & the Consuls, Little Caesar & the Gladiators, Little Caesar & the Empire, Little Caesar & the Euterpeans, and Little Caesar & the Conspirators. There's even a hard rock group, around since the late 1980s, called Little Caesar.

Since Edward G. Robinson's film "Little Caesar" had been released in 1931, I felt confident that it wouldn't get in the way of my research. Guess which film was constantly being re-released (or referred to) during Harry Caesar's heyday? Even worse, there was a small trailer called a "Little Caesar" which popped up, in ads, more than any mention of Robinson's film. I'm just lucky that he stopped calling himself "Little Caesar" before the Little Caesar's pizza chain came along

Since Edward G. Robinson's film "Little Caesar" had been released in 1931, I felt confident that it wouldn't get in the way of my research. Guess which film was constantly being re-released (or referred to) during Harry Caesar's heyday? Even worse, there was a small trailer called a "Little Caesar" which popped up, in ads, more than any mention of Robinson's film. I'm just lucky that he stopped calling himself "Little Caesar" before the Little Caesar's pizza chain came along

When I wrote about Big Boy Groves, I bemoaned the fact that I could only find 5 appearance ads for him in 17 years. Little Caesar beat that record: in his entire career, I couldn't find one single ad for an appearance! (There were a scant few mentioned in blurbs, but no ads. Period.) Because of this, you'll find the article liberally sprinkled with "presumably", "probably", "supposedly", "I have no idea", "beats me", etc.

Harry Caesar was born in Pittsburgh on February 18, 1928 to Alex Caesar, Jr (born in Tifton, Georgia in 1901) and Hattie Chambers (born in Dothan, Alabama in 1906). He had several older siblings: Viola (born in 1922; died 1977), Richard (born in 1924; died 2007), and George (born in 1927; died 1930). There'd also been an unnamed brother (born in 1921), who died at only two days old; and a sister, Ida (born in 1925), who died a little over a year later.

NOTE: I see Harry referred to, in many places, as Horace Caesar. If that was truly his real name, I can't find any evidence of it. He never used it on anything that I have access to: his Army and Social Security records, as well as his voter registration and tombstone, all refer to him as "Harry".

On May 11, 1929, when Harry was little more than a year old, his mother died from meningitis. By the time of the 1930 census, father Alex had moved to Youngstown, Ohio (some 65 miles from Pittsburgh). The big industries in Pittsburgh and Youngstown revolved around steel. The Great Depression was still on and Alex probably moved to Youngstown looking for work. In 1930, he was a laborer in a Youngstown steel mill. However, he didn't take Viola, Richard, George, or Harry with him, probably leaving them with some relatives; I can't find any of them in the 1930 census.

In December 1930, Harry's brother George died, just short of his fourth birthday. He was still living in Pittsburgh and died in a hospital there, although Alex gave a Youngstown address for himself.

In the 1940 census, Richard and Harry were now living with Alex in Youngstown, but there was no trace of Viola; she had either gotten married or was living with some relative (she lived until 1977). Alex was now a laborer in a W.P.A. airport project. [The W.P.A. was used to give public works jobs to those otherwise out of work.]

In the October 28, 1972 New York Amsterdam News, Harry talked about playing a railroad fireman named "Coaly" in the movie "Emperor Of The North Pole" (probably his most famous acting role). [A fireman shovels coal into the engine's boiler.] Because it was relevant to that role, Harry recounted his youth.

In the October 28, 1972 New York Amsterdam News, Harry talked about playing a railroad fireman named "Coaly" in the movie "Emperor Of The North Pole" (probably his most famous acting role). [A fireman shovels coal into the engine's boiler.] Because it was relevant to that role, Harry recounted his youth.

"I grew up on the railroad. In my teens, I was a gandy dancer [a track-layer] working on the Erie and the Pennsy and the B&O around Youngstown. I've talked to lots of railroad men. Seems like I've always been preparing to play Coaly."

"Most firemen in the South were Black in the early days. As everyone knows, Casey Jones' fireman, Sim Webb, was Black. There were Black brakemen too, and Black engineers, at least on the yard engines and on short lines of 200 or 300 miles. What actually happened was that fireman was considered a dirty job and given to Blacks. But when the pay rates began to go up, the railroads stopped using Blacks and used whites. So that by the time the Depression came along, a Black fireman was a rarity. But there were enough of us for my role to be valid."

Harry was born in Pittsburgh, the son of Alex and Hattie Caesar, moved at three to Youngstown with his family, attended Rayen High School and worked the long, hot summers as a gandy dancer (replacing rails on the section) and also as a blacksmith at Youngstown Sheet & Tube's open hearth mill.

In his senior year, Harry entered the Army, drove trucks to East German checkpoints during the 1949 Berlin airlift, then transferred to the 450th Artillery at Fort Ord [near Salinas, California]. There he had a brief, glorious boxing career before he was discharged.

What Harry left out was his gang activity in Youngstown. He belonged to the Wolf Gang and called himself "Kid Wolf" (probably as a tribute to a well-known Memphis boxer named Eddie "Kid" Wolfe). He ended up in jail for a few months, and was then drafted (May 1948), spending two years in the Army.

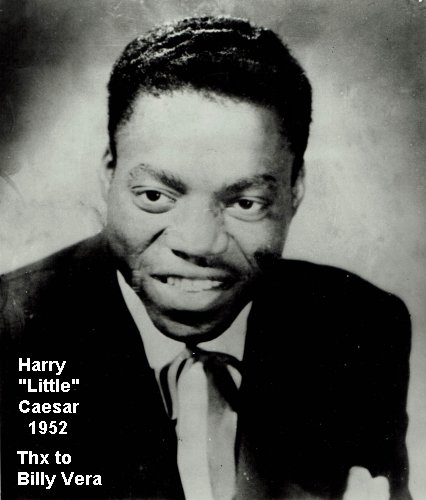

By December 1949, he represented Fort Ord as a heavyweight boxer. He'd already begun to call himself Harry "Little" Caesar.

Once discharged from the Army (in May 1950), Harry intended to become a boxer. In an article in the August 1, 1973 Desert Sun (Palm Springs, California), Harry talked about his short professional boxing career: a single fight: "It was a hometown draw. I knocked the dude out of the ring and they only gave me a draw. I quit." He then disappeared until mid-1952.

Supposedly he stayed in the San Francisco area and appeared with the Peter Rabbit Trio and then the band of Qudellis "Que" Martyn (who'd played tenor sax with Les Hite in the early 1940s). However, there are no ads or references to that in any contemporary papers.

Supposedly he stayed in the San Francisco area and appeared with the Peter Rabbit Trio and then the band of Qudellis "Que" Martyn (who'd played tenor sax with Les Hite in the early 1940s). However, there are no ads or references to that in any contemporary papers.

But in 1952, Little Caesar, generally backed up by Que Martyn's band, began recording for John Dolphin's Recorded In Hollywood label (whose president and sales manager was Franklin Kort). Presumably they traveled down to Los Angeles for the sessions.

But in 1952, Little Caesar, generally backed up by Que Martyn's band, began recording for John Dolphin's Recorded In Hollywood label (whose president and sales manager was Franklin Kort). Presumably they traveled down to Los Angeles for the sessions.

The first Recorded In Hollywood release was "Don't Mention The Blues", backed with "Talkin' To Myself" in the spring of 1952. However, it wasn't sent out for review and sank without a trace. That's a shame, since "Don't Mention The Blues" is a really nice recording.

On July 27, 1952, Little Caesar ("Recorded In Hollywood's sensational new blues-singing find" said the August 9 Cash Box) had been part of the Third Annual Blues Jubilee held at L.A.'s Shrine Auditorium and presented by KLAC DJ Gene Norman. Others on the bill were Big Jay McNeely, T-Bone Walker, Helen Humes, Peppermint Harris, Al Hibbler, Floyd Dixon, Jimmy Witherspoon, Joe Houston, Charlie Norris, and Big Jim Wynn.

Also in July, Recorded In Hollywood released "Going Down To The River", coupled with "Long Time Baby". (Note that, on the label, the title was printed as "Going Down To THE RIVER", so most accounts simply call it "The River".) The August 2 Cash Box made it the "Sleeper Of The Week".

Also in July, Recorded In Hollywood released "Going Down To The River", coupled with "Long Time Baby". (Note that, on the label, the title was printed as "Going Down To THE RIVER", so most accounts simply call it "The River".) The August 2 Cash Box made it the "Sleeper Of The Week".

"The River" was the first of Caesar's despondent songs. In this one, he ends up drowning himself. The August 2 Billboard listed it as a record to watch. Billboard reviewed it in their August 30 edition.

"The River" was the first of Caesar's despondent songs. In this one, he ends up drowning himself. The August 2 Billboard listed it as a record to watch. Billboard reviewed it in their August 30 edition.

The River (80) - This is certainly an item different from the general run of tunes. It drips with mood and melancholy as Little Caesar plaintively philosophizes about his girl. A small ork sets highly effective doleful backdrop with a piano and flute featured. The piano plays simple chords thruout. Disk gets emotional at end with sobs and gurgling water [done with the help of a toilet] as he goes under. Powerful wax, in the vein of "Gloomy Sunday."

Long Time Baby (76) - Pleasant jump tune is sung brightly by Little Caesar. The ork gives it a strong ride all the way with some nice sax work featured between vocals. Could catch some coin. [What they didn't mention was that this is an incredibly raunchy song: "takes a long time baby to break in a brand-new broom. Along with the nice sax work, there's a call and response with the band.]

Walter Winchell, in his syndicated September 6 column mentioned the song: "The hottest 'race' record is 'Going Down To The River,' in which the singer, Little Caesar, goes thru the agony of drowning, gurgles & all. (Another 'Gloomy Sunday'.)"

["Gloomy Sunday" was an incredibly depressing 1941 recording by Billie Holiday, based on a Hungarian song from 1935. It reportedly caused some suicides (although that probably wasn't true), and was actually billed as the "Hungarian Suicide Song".]

The September 6 Billboard reported that New York radio station WINS was going to stop playing "The River".

Mostly it's only when a record is too suggestive or literal in matters romantic that radio stations exercise censorship. But now, some are worried about a tune called "The River," in which sex plays only a minor role.

First waxing of the ditty was by r.&b. chanter Little Caesar. In it he bemoans a romantic disappointment, and ends it all by a leap into the river. The platter closes with a realistic gurgling sound.

Here, local indie WINS has found the disk "too depressing" for exposure to its listeners. It's too much like "Gloomy Sunday," they feel, which about a decade ago was reported to have influenced a minor suicide wave. Other radio stations, like WWRL, have played the record without noticing any appreciable diminution of their listening audience. [a nicely sarcastic turn of phrase]

Meanwhile, a pop version of the ditty has just been released by chanter Art Lund for Coral. Diskery execs feel the new pressing should be acceptable to even the most finicky broadcaster.

You'd think that, with all the hoopla, the record would have become a hit; but it didn't. Sensing this, Dolphin released Caesar's next record, "Goodbye Baby", backed with "If I Could See My Baby" later in September.

You'd think that, with all the hoopla, the record would have become a hit; but it didn't. Sensing this, Dolphin released Caesar's next record, "Goodbye Baby", backed with "If I Could See My Baby" later in September.

"Goodbye Baby" is the first of Little Caesar's records to feature a female voice. Although there would be four others, only one would identify her (but only as "Rusty"). "Goodbye Baby" was the only one in which she's heard throughout the record and not just at the beginning.

"Goodbye Baby" is the first of Little Caesar's records to feature a female voice. Although there would be four others, only one would identify her (but only as "Rusty"). "Goodbye Baby" was the only one in which she's heard throughout the record and not just at the beginning.

Who was Rusty? I dug and dug and came up with this in-depth biography: her name was Margaret Russell. That's it. She was never mentioned anywhere else. I can't even tell you how anyone knows that Rusty's name was Margaret Russell. Supposedly, the two of them had a comedy stage act, but, as I stated before, there are no appearance ads for him.

The September 27, 1952 Cash Box had this:

There's solid satisfaction in reporting that John Dolphin and Franklin Kort have come up with a solid smash on the Recorded In Hollywood label via Little Caesar's second release "Goodbye Baby." [Since it hadn't been sent out for review, it's possible that they didn't even know about "Don't Mention The Blues".] . . . John, whom we've found to be one of the most delightful and cooperative people to do business with in this business, had predicted just this sort of reception for Little Caesar's first disc, "The River", and he had lots of company in this opinion among the top labels' R&B A&R men . . . While "The River" is rolling along nicely and the label will come out way ahead on the publishing deal, which already has a Coral record out by Art Lund, it's "Goodbye Baby" that hit in a hurry where it counts most, over the sales counters and in the jukeboxes of America . . . Already zoomed up to the top of the hot charts in L.A., it's bound to wind up thereabouts cross-country in a few weeks, the way those huge orders have been pouring into the Recorded In Hollywood office by phone, wire and letter. . . . And if we take just a little of the "I knew it was going to happen" position on this one, forgive us, but we did join John Dolphin in his enthusiasm when he rushed up to our office with the studio acetate [sure he did] and gave us a first hearing. . . . Even more dramatic than "The River," "Goodbye Baby has a double homicide for good measure.

At least they remembered to mention Little Caesar's name in this cloying homage to John Dolphin.

In their October 4, 1952 issue, Cash Box gave "Goodbye Baby" its Award O' The Week. This time, they were right: "Goodbye Baby" was a national hit, entering the charts on October 11, 1952 and rising as high as #5 in its 8-week run. Reported in the Cash Box October 4 edition (and therefore from late September), "Goodbye Baby" had already sold 25,000 copies, with another 25,000 back-ordered. That was a pretty substantial R&B hit then and the company was crossing its fingers for 250,000. (Forget anyone who tells you that his R&B record sold a million copies in the early 1950s; it never happened. The Clovers, the most successful group of the early 50s, could get sales as high as 300,000.) Franklin Kort was quoted as saying "We have allocated additional pressing equipment to this one disk, and now have six presses working night and day".

In their October 4, 1952 issue, Cash Box gave "Goodbye Baby" its Award O' The Week. This time, they were right: "Goodbye Baby" was a national hit, entering the charts on October 11, 1952 and rising as high as #5 in its 8-week run. Reported in the Cash Box October 4 edition (and therefore from late September), "Goodbye Baby" had already sold 25,000 copies, with another 25,000 back-ordered. That was a pretty substantial R&B hit then and the company was crossing its fingers for 250,000. (Forget anyone who tells you that his R&B record sold a million copies in the early 1950s; it never happened. The Clovers, the most successful group of the early 50s, could get sales as high as 300,000.) Franklin Kort was quoted as saying "We have allocated additional pressing equipment to this one disk, and now have six presses working night and day".

"If I Could See My Baby", which barely gets any mention, is as down and depressing as "Goodbye Baby", although with no suicidal resolution.

In spite of the activity of "Goodbye Baby" (and all the hype in that September 27 article), Dolphin put out another record in early October (before "Goodbye Baby" had even entered the national charts). This one was "Lying Woman" by "Little Caesar and Rusty", the only time that Rusty was acknowledged on a label. (It's often seen as "Lyin' Woman", even in Recorded In Hollywood ads.) The flip was "Move Me". The October 18 Cash Box said: "Little Caesar, who went kerplunk in 'The River,' has been revived long enough to bring out some new mortgage lifters for Recorded In Hollywood. The two sides to be released are 'Move Me,' a fasty with lots of feeling, b/w 'Lying Woman,' a novelty (this is a novelty?)" [Ladies, don't write me about that last crack; Cash Box is no longer in business.]

In spite of the activity of "Goodbye Baby" (and all the hype in that September 27 article), Dolphin put out another record in early October (before "Goodbye Baby" had even entered the national charts). This one was "Lying Woman" by "Little Caesar and Rusty", the only time that Rusty was acknowledged on a label. (It's often seen as "Lyin' Woman", even in Recorded In Hollywood ads.) The flip was "Move Me". The October 18 Cash Box said: "Little Caesar, who went kerplunk in 'The River,' has been revived long enough to bring out some new mortgage lifters for Recorded In Hollywood. The two sides to be released are 'Move Me,' a fasty with lots of feeling, b/w 'Lying Woman,' a novelty (this is a novelty?)" [Ladies, don't write me about that last crack; Cash Box is no longer in business.]

"Lying Woman" pushed some boundaries. It begins with about 30 seconds of kissing and moaning sounds, before Rusty hears her husband coming and tells her lover to "jump out the window, quick". This is followed by sounds of glass breaking. (Idiot! You're supposed to open the window before jumping out.) Well, the "back-door man" theme was old-hat by this time, but the love-making sounds weren't. As a result, there were stations that refused to play the record at all.

"Lying Woman" pushed some boundaries. It begins with about 30 seconds of kissing and moaning sounds, before Rusty hears her husband coming and tells her lover to "jump out the window, quick". This is followed by sounds of glass breaking. (Idiot! You're supposed to open the window before jumping out.) Well, the "back-door man" theme was old-hat by this time, but the love-making sounds weren't. As a result, there were stations that refused to play the record at all.

The November 22, 1952 Cash Box had an article titled "Lyin' Woman" Banned By Several Stations:

Recorded In Hollywood's latest Little Caesar etching "Lyin' Woman," was the subject of a censorship ban imposed by many local radio stations here [Los Angeles] this past week. Stations refused to play the platter in its entirety on the grounds that it was suggestive.

DJ's instead are playing the record but doing so by skipping the introduction which is deemed controversial.

As a result of their ban, the firm received an added hypo to their already soaring sales of the platter.

Little Caesar last clicked with his current "Goodbye Baby."

In spite of the "added hypo" claim, the song was never a hit (although it was #9 in Philadelphia as reported in the November 29 Cash Box). The Billboard of that date said it was doing well in Buffalo, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and New York. However, it never even made their local charts.

In spite of the "added hypo" claim, the song was never a hit (although it was #9 in Philadelphia as reported in the November 29 Cash Box). The Billboard of that date said it was doing well in Buffalo, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and New York. However, it never even made their local charts.

In January 1953, Recorded In Hollywood released "Here Is A Letter", backed with "You're Part Of Me" by the Red Callender Sextet. Considering that there were plenty of songs in the can, it's a mystery why they didn't put another Little Caesar tune on the back. Regardless, the record wasn't reviewed. "Here Is A Letter" is another depressing song ("read through these teardrops if you can"). He's leaving her for another, although he doesn't say why. However, at the end he changes his mind and won't leave her after all ("we'll get along somehow"). Through it all, go or stay, there's no hint of happiness.

In January 1953, Recorded In Hollywood released "Here Is A Letter", backed with "You're Part Of Me" by the Red Callender Sextet. Considering that there were plenty of songs in the can, it's a mystery why they didn't put another Little Caesar tune on the back. Regardless, the record wasn't reviewed. "Here Is A Letter" is another depressing song ("read through these teardrops if you can"). He's leaving her for another, although he doesn't say why. However, at the end he changes his mind and won't leave her after all ("we'll get along somehow"). Through it all, go or stay, there's no hint of happiness.

February saw two more RIH releases. First was "Do Right Blues", coupled with "Your Money Ain't Long Enough" (another song with Rusty Russell). Next came "Atomic Love", paired with "You Can't Bring Me Down" (on those two, the label misspelled his name "Ceasar".)

February saw two more RIH releases. First was "Do Right Blues", coupled with "Your Money Ain't Long Enough" (another song with Rusty Russell). Next came "Atomic Love", paired with "You Can't Bring Me Down" (on those two, the label misspelled his name "Ceasar".)

Strangely, when Recorded In Hollywood put out an ad later that month, Linda Hayes' "Atomic Baby" was mentioned, but it didn't say what the flip of "You Can't Bring Me Down" was. Possibly they were afraid of too much radiation in the ad.

Strangely, when Recorded In Hollywood put out an ad later that month, Linda Hayes' "Atomic Baby" was mentioned, but it didn't say what the flip of "You Can't Bring Me Down" was. Possibly they were afraid of too much radiation in the ad.

Cash Box reviewed "Your Money Ain't Long Enough" in their March 7 edition, giving it a "B+" ("Little Caesar sings a quick beat novelty item in his accomplished manner. Opens with a telephone call from fem who wants to know "how come?', and Caesar explains 'he wants her, but her money ain't long enough.' Bright, belted, and bouncy.") "Do Right Blues" got a "B" ("Caesar sings a slow blues on the lower lid and gives an emotional reading. Orking is softish but torrid.") "Do Right Blues" is another somewhat depressing song. He made her leave and now regrets it ("If she don't come back, I'll go through life just feeling sad"). At least he's not talking about suicide this time.

In that same Cash Box issue, there was a little blurb talking about how "You Can't Bring Me Down" was the third generation of songs spawned by Willie Mabon's "I Don't Know", a song I've always found annoying, for some reason. ("Yes, I Know", in versions by Annisteen Allen and Linda Hayes was the second generation.) A competing version of "You Can't Bring Me Down" was by Oscar McLollie (vocal by Paul Clifton).

Caesar's (or Ceasar's, if you want to go by the label) "You Can't Bring Me Down" was reviewed in the March 14 Cash Box. It got a "B+" ("Number 3 in the 'I Don't Know' series is waxed in a style that is calculated to keep the battle going for at least one more spin around the wax. Apparently the public is interested in what comes next in this story and diskeries are out to oblige. Ceasar chants with appeal.") "Atomic Love" (which is actually a love song, although with an odd melody) only got a "C+" ("Flip is a melodic slow beat in the pop style. The chanter does ok but the engineering seems off.")

Caesar's (or Ceasar's, if you want to go by the label) "You Can't Bring Me Down" was reviewed in the March 14 Cash Box. It got a "B+" ("Number 3 in the 'I Don't Know' series is waxed in a style that is calculated to keep the battle going for at least one more spin around the wax. Apparently the public is interested in what comes next in this story and diskeries are out to oblige. Ceasar chants with appeal.") "Atomic Love" (which is actually a love song, although with an odd melody) only got a "C+" ("Flip is a melodic slow beat in the pop style. The chanter does ok but the engineering seems off.")

In "You Can't Bring Me Down", she's going to see a lawyer to get what she can from the relationship. But he's not worried because "everything you bought is in my name".

Here's one of the very few times Little Caesar was mentioned in the press (the June 4, 1953 Los Angeles Times). He was part of the "Sweet And Hot Revue" at the Orpheum Theater. It also had the Robins, Murt Lynn, Slappy White, and Harry Edison's orchestra. Starting on June 3, it probably only ran for a week.

The June 13, 1953 Cash Box informed us that Little Caesar had been signed by Bob Geddins' Big Town Records. His first release, in July, was "Big Eyes" (another one with Rusty Russell), coupled with "Can't Stand It All Alone".

The June 13, 1953 Cash Box informed us that Little Caesar had been signed by Bob Geddins' Big Town Records. His first release, in July, was "Big Eyes" (another one with Rusty Russell), coupled with "Can't Stand It All Alone".

These were reviewed in the July 18 Cash Box. "Big Eyes" got a "B+" ("A slow beat novelty. Caesar tells his girl she has big eyes, but they won't pay his rent. Get a bankroll and then call on the telephone. ["If you don't think you can do it," he says, "please give me whole lots of leave me alone".] Cute and could go big in the boxes. Theme reminiscent of one Caesar did on his former label.") "Can't Stand It All Alone" only rated a "C+" ("Little Caesar sings a quick beat pleading with his gal to come back to him. A routine effort.") This one's a familiar theme, but it's not done depressingly.

These were reviewed in the July 18 Cash Box. "Big Eyes" got a "B+" ("A slow beat novelty. Caesar tells his girl she has big eyes, but they won't pay his rent. Get a bankroll and then call on the telephone. ["If you don't think you can do it," he says, "please give me whole lots of leave me alone".] Cute and could go big in the boxes. Theme reminiscent of one Caesar did on his former label.") "Can't Stand It All Alone" only rated a "C+" ("Little Caesar sings a quick beat pleading with his gal to come back to him. A routine effort.") This one's a familiar theme, but it's not done depressingly.

For a change, Billboard agreed with Cash Box, giving "Big Eyes" a 75 and the flip a 65.

John Burton sent me a scan of "Big Eyes" on the "Little Caesar Records" label (with the same number as Big Town). Presumably it was a vanity pressing that he could sell at appearances.

John Burton sent me a scan of "Big Eyes" on the "Little Caesar Records" label (with the same number as Big Town). Presumably it was a vanity pressing that he could sell at appearances.

However, Caesar quit Big Town almost immediately; leaving them for the Bihari Brothers' RPM Records. In October, RPM released "Chains Of Love Have Disappeared", backed with "Tried To Reason With You Baby". The RPM label also misspelled his name "Ceasar". It would be his only RPM disk.

However, Caesar quit Big Town almost immediately; leaving them for the Bihari Brothers' RPM Records. In October, RPM released "Chains Of Love Have Disappeared", backed with "Tried To Reason With You Baby". The RPM label also misspelled his name "Ceasar". It would be his only RPM disk.

Billboard reviewed them in its October 31, 1953 edition. "Chains Of Love Have Disappeared" got a 78 ("Little Ceasar has himself a good disk in this blues effort. It has a provocative beat, and the singer kicks in with a fine performance. Could stir some action.") "Tried To Reason With You Baby" got a 72 ("Routine blues is given a lot of sparkle via singer's shouting.")

A second Big Town record came out in November: "(The Rat Song) Wonder Why I'm Leaving", paired with "What Kind Of Fool Is He" (the last song with Rusty Russell). Billboard reviewed them in its November 14 issue. "What Kind Of Fool Is He" received a 73 ("Caesar sings this sad blues with a lot of heart and feeling. Tune isn't too bright, but his vocal could help it get some spins, in spite of a too talky opening.") "Wonder Why I'm Leaving" got a 70 ("Little Caesar, on his first cutting for the label [How soon they forgot "Big Eyes"!], lets the world know that he can't stand a woman who gets into as much trouble as his does, and that is why he is leaving. Unimpressive disking.")

A second Big Town record came out in November: "(The Rat Song) Wonder Why I'm Leaving", paired with "What Kind Of Fool Is He" (the last song with Rusty Russell). Billboard reviewed them in its November 14 issue. "What Kind Of Fool Is He" received a 73 ("Caesar sings this sad blues with a lot of heart and feeling. Tune isn't too bright, but his vocal could help it get some spins, in spite of a too talky opening.") "Wonder Why I'm Leaving" got a 70 ("Little Caesar, on his first cutting for the label [How soon they forgot "Big Eyes"!], lets the world know that he can't stand a woman who gets into as much trouble as his does, and that is why he is leaving. Unimpressive disking.")

Little Caesar then disappeared for a year. Late in 1954, he somehow hooked up with a group called the Turbans, from Oakland, California: Al Williams (first tenor), Burl Carpenter (second tenor), Charles Fitzpatrick (tenor), Willie Roland (baritone), and Andre Goodwin (bass). Caesar took them to John Dolphin, where they had a four-song session on December 30 of that year: "Tick Tock-A-Woo", "No No Cherry", "The Nest Is Warm (But The Goose Is Gone)", and "When I Return". The only one Caesar sang lead on was "The Nest Is Warm (But The Goose Is Gone)". Was he actually on the others? I have no idea, although he was one of the writers of "Tick Tock A-Woo" and "No No Cherry.

Dolphin released them on his new Money label, starting with "Tick Tock-A-Woo", coupled with "No No Cherry" in January 1955.

Dolphin released them on his new Money label, starting with "Tick Tock-A-Woo", coupled with "No No Cherry" in January 1955.

Billboard reviewed them in its March 19, 1955 edition. "Tick Tock A-Woo" got a mediocre 68 ("Okay group rocker novelty.") "No No Cherry" didn't fare as well, only garnering a 60 ("A slender, dubious, desperate slice.") Even if you don't agree with that review, you have to appreciate the language.

Billboard reviewed them in its March 19, 1955 edition. "Tick Tock A-Woo" got a mediocre 68 ("Okay group rocker novelty.") "No No Cherry" didn't fare as well, only garnering a 60 ("A slender, dubious, desperate slice.") Even if you don't agree with that review, you have to appreciate the language.

In spite of Billboard, "Tick Tock A-Woo" was a local hit in Los Angeles, reaching #5 on February 19.

At some point, Dolphin re-released "Tick Tock-A-Woo", this time with "The Nest Is Warm (But The Goose Is Gone)" on the flip, but used the same record number.

Around August, Dolphin issued "When I Return". However, he now had no fourth Turbans song for the flip, so he stuck on "Emily" by the "Turks" (which was actually by the Hollywood Flames).

Around August, Dolphin issued "When I Return". However, he now had no fourth Turbans song for the flip, so he stuck on "Emily" by the "Turks" (which was actually by the Hollywood Flames).

"When I Return" was reviewed in the October 29 Billboard, receiving a 74 ("The boys wail with telling effect on a moving ballad with a great beat.")

After that, the Turbans left Dolphin and wandered off to Imperial Records, where they recorded "Since I Fell For You" and "Made To Love". But there was a problem. A Philadelphia group of Turbans came along and had a big smash with "When You Dance", which entered the national charts in November. Therefore, when Imperial issued the tunes (on its Post subsidiary), the Turbans had been transformed into the "Sharptones".

After that, the Turbans left Dolphin and wandered off to Imperial Records, where they recorded "Since I Fell For You" and "Made To Love". But there was a problem. A Philadelphia group of Turbans came along and had a big smash with "When You Dance", which entered the national charts in November. Therefore, when Imperial issued the tunes (on its Post subsidiary), the Turbans had been transformed into the "Sharptones".

The Sharptones record wasn't reviewed and the group fell apart. (However, while Caesar was one of the writers of "Made To Love", it's unclear whether he was actually on the Sharptones recordings.)

Little Caesar wasn't heard from again for another two and a half years, when he turned up on RCA for a single release in June 1958: "Who Slammed The Door", backed with "I'm Reachin'". Both have the Dread Chorus.

Little Caesar wasn't heard from again for another two and a half years, when he turned up on RCA for a single release in June 1958: "Who Slammed The Door", backed with "I'm Reachin'". Both have the Dread Chorus.

The disc was reviewed in the June 21 Cash Box. "Who Slammed The Door" got a "B" ("The artist, whose name belies a basso-like delivery, gets off a rocker built humorously around the title. Happy-go-lucky jumper.") "I'm Reachin'" pulled down a "C+" ("Caesar kicks up a storm in reachin' for his gal's love. Side also moves at a merry r&r pace.")

Once, "Who Slammed The Door" would have been a reference to someone who'd been with his woman and was sneaking out the back (as in "Lying Woman"). Now, in the age of rock & roll, it's just a brainless, meaningless, annoying repetition of "who slammed the door". Neither side was worthy of Caesar.

When that record sank without a trace, so did Caesar for another year and a half. The next time we hear from him is in mid-1960, when he turned up on the Jack Bee label, owned by Bill Wenzel of Wenzel’s Music Town in Downey, California. The label was named for Bill's son, Jack, with Bill being the "Bee". (There were some half dozen Jack Bee releases before the name was changed to Downey Records.)

By this time, Caesar had his own band, called the Ark Angels, about which nothing is known. They recorded at least eight sides for Jack Bee: "What Are They Laughing About", "I Hope That It's Me", "The Ghost Of Mary Meade" (vocal and instrumental versions), "Baby What’s That You Got", "Personal Question", "Show Me The Time", and "In Lonelyville" (aka "Lonely Town"). On these, Caesar sounds a bit like Brook Benton.

Jack Bee released "What Are They Laughing About" and "I Hope That It's Me" around February 1960. They were reviewed in the March 21 Billboard: "I Hope That It's Me" got three stars ("Little Caesar sings soulfully here. It's a ballad with a modified triplet figure.") "What Are They Laughing About" got two stars ("Melody is a bouncy one. Vocal gimmick is a spate of wild laughter. Chanter, when the laughter ends, gets some soul in the vocal.")

Jack Bee released "What Are They Laughing About" and "I Hope That It's Me" around February 1960. They were reviewed in the March 21 Billboard: "I Hope That It's Me" got three stars ("Little Caesar sings soulfully here. It's a ballad with a modified triplet figure.") "What Are They Laughing About" got two stars ("Melody is a bouncy one. Vocal gimmick is a spate of wild laughter. Chanter, when the laughter ends, gets some soul in the vocal.")

"The Ghost Of Mary Meade" (parts 1 and 2) was issued in late March and reviewed in the April 11 Billboard. They gave it two stars: "Folkish ballad is nicely handled by the lead singer. Backing includes lush strings. It can move for pop and c.&w. coin. Side two is an instrumental version." I can't really figure out who they thought the audience for this strange side would have been.

"The Ghost Of Mary Meade" (parts 1 and 2) was issued in late March and reviewed in the April 11 Billboard. They gave it two stars: "Folkish ballad is nicely handled by the lead singer. Backing includes lush strings. It can move for pop and c.&w. coin. Side two is an instrumental version." I can't really figure out who they thought the audience for this strange side would have been.

And, once again, Caesar disappears for a stretch. This time, he resurfaces on the Ride label in 1964 (as "Sir Ceaser"). The titles are two that he'd previously recorded for Jack Bee ("What Are They Laughing About" and "Show Me The Time"). "Show Me The Time" is a vastly different arrangement from the one on Jack Bee; I've never heard "What Are They Laughing About", but that was probably re-arranged also. The record (his last) was never reviewed.

And, once again, Caesar disappears for a stretch. This time, he resurfaces on the Ride label in 1964 (as "Sir Ceaser"). The titles are two that he'd previously recorded for Jack Bee ("What Are They Laughing About" and "Show Me The Time"). "Show Me The Time" is a vastly different arrangement from the one on Jack Bee; I've never heard "What Are They Laughing About", but that was probably re-arranged also. The record (his last) was never reviewed.

There's a 1970 record of Harry Caesar marrying Marion K. Bernot, in Los Angeles on November 21, 1970. However, in the 1960 and 1962 California Voter Registration records, she already appears as "Marion K. Caesar" at the same address as Harry. Beats me. They would have three daughters: Jacqueline, Valerie, and Kimberly.

There's a 1970 record of Harry Caesar marrying Marion K. Bernot, in Los Angeles on November 21, 1970. However, in the 1960 and 1962 California Voter Registration records, she already appears as "Marion K. Caesar" at the same address as Harry. Beats me. They would have three daughters: Jacqueline, Valerie, and Kimberly.

After the Ride record, Caesar turned to acting. I believe his first job was in "The Graduate" (1967). He talked about it in the August 1, 1973 Desert Sun article previously referenced.

He was an extra on "The Graduate," standing in the back in a crowd scene. Director Mike Nichols asked, "Who's got that loud voice?" It was Caesar, so Nichols moved him up and gave him some lines. That's how he became an actor.

While beyond the scope of this article, you'll find a list of his known acting credits after the discography.

Caesar continued singing in between acting jobs, although his recording days were over. In the Eighties, he appeared with Joe Liggins' Honeydrippers on many occasions. For example, the February 18, 1986 San Francisco Examiner had this (talking about Liggins appearing at Don Barksdale's Showcase in Oakland): "Vocalist Harry Caesar, still in good voice and looks, is mesmerizing...." Singer Billy Vera told me: "I did see him perform, with Joe Liggins, circa 1980. But he just sang some tired old warhorses, so it wasn't very interesting. He knew that nobody by that time knew anything about his records."

In April 1992, he was one of the performers at the Desert Dixieland Jazz 7 at the Riviera Resort Hotel in Palm Springs, California. The April 26 Desert Sun said (talking about Louis Thomas & His Pieces Of Eight; remnants of the Joe Liggins Honeydrippers): "Particularly noteworthy was the band's vocalist, Harry Caesar, known as Little Caesar in blues circles. Caesar, who also had acting roles in such films as 'The Longest Yard' and 'Lady Sings The Blues,' stood with the help of a cane, but impressed with a soulful, mellifluous baritone."

In April 1992, he was one of the performers at the Desert Dixieland Jazz 7 at the Riviera Resort Hotel in Palm Springs, California. The April 26 Desert Sun said (talking about Louis Thomas & His Pieces Of Eight; remnants of the Joe Liggins Honeydrippers): "Particularly noteworthy was the band's vocalist, Harry Caesar, known as Little Caesar in blues circles. Caesar, who also had acting roles in such films as 'The Longest Yard' and 'Lady Sings The Blues,' stood with the help of a cane, but impressed with a soulful, mellifluous baritone."

Harry "Little" Caesar died on June 12, 1994 in Los Angeles, supposedly due to complications from diabetes. As is all too common, I can't find an obituary.

I really like Little Caesar, at least in his early days. While several of his records can be looked on as depressing, he found a niche for himself. There was precious little written about him, but nothing ever said, or hinted, that the man himself was depressing.

Special thanks to Matt The Cat, Victor Pearlin, and Billy Vera.

LITTLE CAESAR (RR = with Margaret "Rusty" Russell, usually uncredited)

RECORDED IN HOLLYWOOD

233 Don't Mention The Blues / Talkin' To Myself - 52

234 Going Down To The River / Long Time Baby - 7/52

235 Goodbye Baby (RR) / If I Could See My Baby - 9/52

236 Lying Woman (RR) / Move Me - 10/52

237 Here Is A Letter / [You're Part Of Me - Red Callender Sextet] - 53

238 Do Right Blues / Your Money Ain't Long Enough (RR) - 2/53

239 Atomic Love / You Can't Bring Me Down - 2/53

BIG TOWN

106 Big Eyes (RR) / Can't Stand It All Alone - 7/53

110 (The Rat Song) Wonder Why I'm Leaving / What Kind Of Fool Is He (RR) - 11/53

RPM

393 Chains Of Love Have Disappeared / Tried To Reason With You Baby - 10/53

UNRELEASED RPM

Cadillac Baby

MONEY (as part of the Turbans)

209 Tick Tock-A-Woo / No No Cherry – 1/55

209 Tick Tock-A-Woo / The Nest Is Warm (But The Goose Is Gone) - 55

211 When I Return / [Emily - Turks] - ca 8/55

POST (Imperial subsidiary; Turbans have been renamed the "Sharptones")

2009 Since I Fell For You / Made To Love - 11/55

RCA

47-7270 Who Slammed The Door / I'm Reachin' - 6/58

JACK BEE (Little Caesar & Ark Angels)

1005 What Are They Laughing About / I Hope That It's Me - ca 2/60

1008 The Ghost Of Mary Meade / [instrumental version] - ca 3/60

JACK BEE UNRELEASED (recorded 1960)

Baby What’s That You Got

Personal Question

Show Me The Time

In Lonelyville (aka Lonely Town)

RIDE (Sir Caesar with C. Tillman Band; on label as "Sir Ceaser")

140 What Are They Laughing About / Show Me The Time - 64

HARRY CAESAR'S ACTING CREDITS

1967 The Graduate (uncredited)

1969 Julia (TV Series; one episode)

1970 Barefoot in the Park (TV Series; one episode)

1970 Mannix (TV Series; one episode)

1970 There Was a Crooked Man

1972 Lady Sings the Blues

1972 (TV Series; one episode)

1972 Trouble Man Walter

1973 Emperor of the North Pole (aka "Emperor Of The North")

1973 Roll Out (TV Series; one episode)

1973 Sanford and Son (TV Series; two episodes)

1974 The Longest Yard

1975 Baretta (TV Series; two episodes)

1975 Farewell, My Lovely

1975 The Blue Knight (TV Series; one episode)

1977 Police Story (TV Series; one episode)

1977 The Amazing Spider-Man (TV Series; one episode)

1977 The Greatest Thing That Almost Happened (TV Movie)

1978 Casey's Shadow

1978 Good Times (TV Series; one episode)

1978 The Big Fix

1978 The End

1979 Boulevard Nights

1979 Disaster on the Coastliner (TV Movie)

1979 Hart to Hart (TV Series; one episode)

1980 A Small Circle of Friends

1980 Angel on My Shoulder (TV Movie)

1980 B.J. and the Bear (TV Series; one episode)

1980 CBS Afternoon Playhouse (TV Series; five episodes)

1981 The Dukes of Hazzard (TV Series; one episode)

1982 Barbarosa

1982 The Ambush Murders (TV Movie)

1982 The Escape Artist

1982 Thou Shalt Not Kill (TV Movie)

1983 Cagney & Lacey (TV Series; one episode)

1983 (TV Series; one episode)

1983 Hill Street Blues (TV Series; one episode)

1983 Murder 1, Dancer 0 (TV Movie)

1984 Breakin' 2: Electric Boogaloo

1984 City Heat

1984 Hill Street Blues (TV Series; one episode)

1984 The New Mike Hammer (TV Series; one episode)

1984 The Paper Chase (TV Series; one episode)

1985 MacGyver (TV Series; one episode)

1986 L.A. Law (TV Series; two episodes)

1986 North and South, Book II (TV Mini-Series)

1987 From a Whisper to a Scream

1987 Retribution

1987 Stranded

1987 The Ladies (TV Movie)

1987 What's Happening Now! (TV Series; one episode)

1988 Hot to Trot

1989 Alien Nation (TV Series; one episode)

1989 Ghetto Blaster

1989 Homer and Eddie

1989 L.A. Law (TV Series; one episode)

1990 Bird on a Wire

1990 Murder in Mississippi (TV Movie)

1992 A Few Good Men

1992 Roadside Prophets

1993 Evening Shade (TV Series; one episode)

1993 Josh and S.A.M.