The Orioles - Part 1

The Early Jubilee Years

1948-1951

By Marv Goldberg

based on interviews with Sonny Til, Johnny Reed,

Albert "Diz" Russell, Bobby Thomas, Gregory Carroll,

George Grant, and Deborah Chessler

© 1999, 2009 by Marv Goldberg

NOTE: Here are some personal reminiscences of having interviewed Sonny Til: Memories Of Sonny Til.

On January 12, 1995, in a ceremony in New York City's Waldorf-Astoria

Hotel, the Orioles were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

It's probable that most of the audience [record company executives for

the most part], never heard of the Orioles or knew of their contribution

to the music. And what was that contribution? The Orioles literally

inspired an entire generation of black singers. Their heirs then

went on to take Rhythm and Blues (a black music genre) and transform it

into Rock And Roll. In other words, this (nowadays) obscure group from

Baltimore is the reason that the Hall Of Fame exists

today. Period. Whether it's realized or accepted is unimportant. The

Orioles, while certainly not the first practitioners of their art, were

the first to make it big, very big.

Sonny Til, lead singer of the Orioles, was born Earlington Carl Tilghman

in Baltimore, in 1925. He picked up the nickname "Sonny" from his favorite record as a

child: Al Jolson's "Sonny Boy." From the start, Sonny knew he wanted to

be an entertainer. As he told me:

I had a group in high school. I don't even remember the name we had. There were just the three of us. I forget the name. In my class book, I said I want to be a singer; I want to make it in show business. And God let me make it, so I'm very happy it was fulfilled.

In the service, I did a lot of Special Services work: singing and entertaining. But also my duties in war, too, 'cause we were a combat unit overseas. I was a smoke layer in the Chemical Corps. In the states, I'd sing with a lot of army bands, did a lot of shows, USO shows. I was in for almost three years. I got out at the end of the war. I came right out of school right into the army. I wanted to go, though. I wanted to get away from home. (Not exactly "right out" of school, Sonny enlisted on October 29, 1943, two months after his eighteenth birthday; he was discharged on April 4, 1946.)

When I got out of the army, all I wanted to do was sit around the house and be with my girl. All I wanted to do was nothing. I had seen friends of mine blown apart and I was happy that I wasn't scratched; getting home from overseas and not being hurt. I just wanted to relax and be peaceful.

I did start working, at a place called Hold-Tite, which was a rubber heel factory. Then I took a job at Kernan Motors, as a driver/delivery boy on a truck. I was a little more free.

Sonny took the amateur show route and that's how the Orioles were born. Things began to come together at Elmer Youse's Avenue Cafe in 1946, where Sonny began singing in the amateur shows. Sonny told me:

I started going to this club that used to have amateur shows: the Avenue Cafe. I began to win some shows and I met the guys who became the Orioles. One was the M.C. there [George Nelson] that I knew 'cause he lived in my neighborhood. One was playing bass with the band [Johnny Reed]. Alex Sharp was a singer who was on some of the shows too. So we began to win. One week Allie would win; one week I'd win; one week George's girlfriend would win. Then we decided to get a group together. We used to go out on the corner of the club at night and sing out there and the guys would throw us fifty cents, a dollar. That's how we started, as a street singing group.

And later, Deborah Chessler, who was to become our manager, heard us and she wrote some songs for us. She said she'd like to help us and became our manager.

Tommy Gaither? Well, we needed a guitar player in the group. I don't remember how it came about with Tommy. Some way he got with us through friends. We rehearsed and he stuck with us.

Actually, Sonny's pre-Orioles appearances were more extensive than he remembered. Researcher Charlie Horner has found him billed at clubs with every possible variant of "Sonny," "Earl," "Til," and "Tilghman." Clearly, he was searching for his identity. For example, the August 17, 1946 edition of the Baltimore Afro-American lists the winners of the weekly Wednesday night talent contest: first prize, George Nelson; second prize, Sonny Tilghman; third prize, Harry Whitlock. The members of the (unnamed) house band were: Bus Jackson (piano), Robert "Tan Feet" Hines (drums), John Burke (trumpet), Henry Baker (tenor sax), and Johnny Reed (bass). (Another article names them as the Avenue Playboys, with whom saxophonist William Ross had been and would again be a member.)

Actually, Sonny's pre-Orioles appearances were more extensive than he remembered. Researcher Charlie Horner has found him billed at clubs with every possible variant of "Sonny," "Earl," "Til," and "Tilghman." Clearly, he was searching for his identity. For example, the August 17, 1946 edition of the Baltimore Afro-American lists the winners of the weekly Wednesday night talent contest: first prize, George Nelson; second prize, Sonny Tilghman; third prize, Harry Whitlock. The members of the (unnamed) house band were: Bus Jackson (piano), Robert "Tan Feet" Hines (drums), John Burke (trumpet), Henry Baker (tenor sax), and Johnny Reed (bass). (Another article names them as the Avenue Playboys, with whom saxophonist William Ross had been and would again be a member.)

In the spring of 1948, the 23-year-old Sonny Til put together a group, called the Vibra-Naires, consisting of his friends first tenor Alex Sharp, baritone George Nelson, and guitarist/second tenor Tommy Gaither. The bass/bassist was supposed to be Johnny Reed (who was no longer listed as a member of the Avenue Playboys at the time), but it was a bit more complicated than that, as we'll soon see. Strangely, according to Johnny, the group itself never appeared at the Avenue Cafe.

In 1948, the ages of the Orioles were approximately: Sonny Til (23), George Nelson (25), Johnny Reed (25), and Tommy Gaither (29). Alex Sharp, the youngest of the group, was about 20.

Johnny Reed would become the bass (and bassist) of the Orioles. Here's what he told me about his early days in the Baltimore music scene:

Music's been my life ever since I left the grocery store. I was 14 years old, and I was working in a meat market and I used to play that little ukulele on the steps in Baltimore. Sit on those marble steps (after you washed them); they'd take the chairs out every evening and I'd be out there with my uke. Until they ran me out: "Get out of here with that thing."

Ike Dixon at the Comedy Club let me play the bass that they had there.... So later on he said "I'll let you work with the band if you want to." He bought a second-hand fiddle [bass] for me. He said, "It's gonna stay here until it's paid for."

Up the street, on the next block was Gambit's. Mack Crockett and the Dukes of Rhythm were there. I played with them for a while. After Gambit's, I went up the street, across from the Regent Theater, to the Avenue Cafe [on Pitcher Street and Pennsylvania Avenue] and worked with William Ross and his Avenue Playboys.

Johnny Reed was a bit unclear about the earliest days, but apparently Sonny wanted him to join as bass, so that they could go to New York to appear on the Arthur Godfrey Talent Scouts radio show. However, Johnny was a professional musician—a union member—and felt he couldn't go on this amateur program. So from somewhere, Sonny got bass Richard Williams to round out the group, and off they went to New York.

Enter Faith Shirley "Deborah" Chessler ("Deborah" was her mother's middle name), a Baltimore salesgirl who was also a fledgling songwriter. In March of 1948, the first of her songs was recorded by Savannah Churchill on the Manor label: "Tell Me So." While the song didn't become a hit this time around, it would later on.

Enter Faith Shirley "Deborah" Chessler ("Deborah" was her mother's middle name), a Baltimore salesgirl who was also a fledgling songwriter. In March of 1948, the first of her songs was recorded by Savannah Churchill on the Manor label: "Tell Me So." While the song didn't become a hit this time around, it would later on.

One night, Deborah got a call from a man named Abe Shaffer, who'd been approached by the Vibra-Naires in the hopes that he'd manage them. He'd helped them make some demos, but now he was stuck. He was married with a young son and couldn't devote the time to being a manager. Not knowing what to do, he called Deborah (a friend of his sister-in-law), and asked her to listen to them. The group sang "Two Loves Have I," "I Cover The Waterfront," and "Exactly Like You" for her over the phone, and she was hooked.

Interestingly, I was contacted by Abe Shaffer's son, Howard M. Shaffer-Kramer, who related this story:

My father was a regional music talent scout in the late 1940s and very early 1950s for the long-gone Jubilee record label. We lived in Baltimore, Maryland and I was very young at the time. I do remember traveling with him by train to New York on "business." I assume that Jubilee was based in New York City and his work for them was the reason for the travel. In our living room at home, we had a huge Philco record player and record making machine. That is to say, you could play records on it, but also perform into a microphone and burn a record on a blank disk with a second heavy tone arm. I remember standing on a chair and watching the curly ribbons of wax or vinyl piling up as the record was being recorded. On Sunday afternoons, I recall a group of singers coming over to the house to record these one-of-a-kind records. The group was made up of men, but occasionally a woman would join them. As a little white boy, I was fascinated, as they were the first African-American people that I can ever recall seeing. I loved to listen to them as they sang the same song over and over before my father would finally make a record on the Philco. As it turned out, this vocal group was called the Orioles, who eventually went on to a fair degree of fame.

Using their demos of "Two Loves Have I," "Exactly Like You," "I Cover The Waterfront," and "Donkey Serenade," Deborah had her uncle drive her and her mother around to black clubs in the Baltimore area. She would introduce herself to the owners, tell them she had a group, and play the demos. Once she did, they invariably hired the group.

Sonny said:

I am proud and happy to say that Deborah Chessler was our manager. She made it possible for the Orioles to become whatever we became because she managed us and she wrote a lot of the tunes which became big hits for us. When we met her, she was a saleslady.

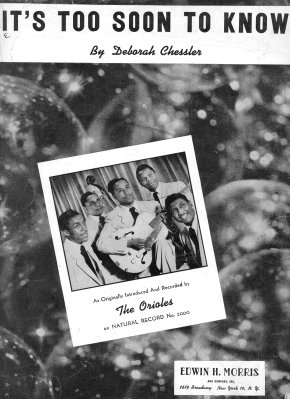

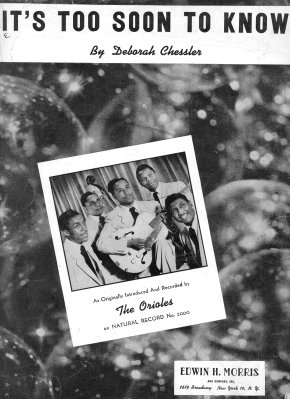

Strangely, Deborah wrote relatively few songs that the group recorded: "It's

Too Soon To Know," "Barbra Lee," "Tell Me So," "Forgive And Forget,"

"I'm Just A Fool In Love," "A Scandal," "Two Party Line," and "I Need You Baby" were all her

compositions. She was also co-writer of "Waiting" and "Teardrops On My

Pillow." In addition, there were a few songs that others (but not the Orioles) recorded, such as "Before

It's Too Late" (Sunny Gale, Bobby Colt), "Once In Every Lifetime" (Sunny Gale),

and "Always A Bridesmaid" (Jo Anne Tolley).

Deborah's biggest coup was getting the Vibra-Naires an appearance on the prestigious Arthur Godfrey Talent Scouts radio show in New York. On Monday, May 3, 1948, they all got on a train to New York. "All" included Sonny Til, Alex Sharp, George Nelson, Tommy Gaither, temporary bass Richard Williams, Deborah Chessler, her mother, Irene "Mom" Chessler, and Shirley Greenberg. Shirley, the cousin of Deborah's ex-husband, was the "talent scout" who actually presented the group on the show. In those days, said Deborah, the show's policy was not to have an act's manager do the presenting. (Note that Deborah wrote "Barbara Lee" for Shirley's daughter.)

Strangely, in those days, the names of the acts were given to newspapers ahead of time. Thus, the May 2 Kansas City Star reported "the competition tomorrow night consisting of Kjerstin Dellert, Swedish mezzo-soprano; Chicago tenor Larry White; English pianist George Sheering [sic]; and the Vibra-naires [sic], a quartet from Baltimore."

Strangely, in those days, the names of the acts were given to newspapers ahead of time. Thus, the May 2 Kansas City Star reported "the competition tomorrow night consisting of Kjerstin Dellert, Swedish mezzo-soprano; Chicago tenor Larry White; English pianist George Sheering [sic]; and the Vibra-naires [sic], a quartet from Baltimore."

The Vibra-Naires sang "Exactly Like You," a song that Ruth Etting had made a hit in 1930. The winner of the contest (who got to appear on Godfrey's weekday morning radio show) was indicated by a sound meter reacting to audience applause. While they had high hopes, the Vibra-Naires came in third, losing to blind pianist George Shearing (selected as the winner by Godfrey) and Kjerstin Dellert (who seemed to be the one that the studio audience preferred). Since they didn't win, they simply packed up and went home; Deborah was back at her salesgirl's job the next day.

What the Vibra-Naires didn't realize was that they'd made a much bigger hit with the listening audience than with the studio audience. This caused the show to receive several thousand phone calls, letters, and telegrams and Godfrey wanted them to appear on his daytime radio show (Arthur Godfrey Time) in spite of their loss. On Thursday (May 6), when Deborah got home from work, she found a telegram (mistakenly addressed to "G. Chessler") from the show's producer: "Please phone me immediately regarding the appearance of the Vibronaires [sic] on the Arthur Godfrey show tomorrow Friday May 7."

What the Vibra-Naires didn't realize was that they'd made a much bigger hit with the listening audience than with the studio audience. This caused the show to receive several thousand phone calls, letters, and telegrams and Godfrey wanted them to appear on his daytime radio show (Arthur Godfrey Time) in spite of their loss. On Thursday (May 6), when Deborah got home from work, she found a telegram (mistakenly addressed to "G. Chessler") from the show's producer: "Please phone me immediately regarding the appearance of the Vibronaires [sic] on the Arthur Godfrey show tomorrow Friday May 7."

The next day, everyone took off from work again and they all caught an early train for New York. On Arthur Godfrey Time (which began at 11:00 AM), they reprised their version of "Exactly Like You." Then it was back on the train to Baltimore. As Deborah said: "We had no money; we couldn't afford to stay in a hotel."

Once they triumphantly returned to Baltimore, Johnny Reed was in and Richard Williams was out. Says Johnny, "I didn't know Richard Williams. I didn't see him when he went up there and I didn't see him when he came back... Richard disappeared just as fast as he'd come in." (Williams would surface again in the early 60s as part of Sonny and the Dukes, who also backed up George Jackson as the Unisons.)

Deborah Chessler remembers Richard Williams as "A tiny little guy. He didn't look like any of the others; he didn't fit in. And then they found Johnny. After the Godfrey show, Richard didn't show up to a rehearsal, and at the next one they had Johnny."

Deborah Chessler remembers Richard Williams as "A tiny little guy. He didn't look like any of the others; he didn't fit in. And then they found Johnny. After the Godfrey show, Richard didn't show up to a rehearsal, and at the next one they had Johnny."

Interestingly, the Baltimore Afro-American reported, on May 15, that the Vibra-Naires had recorded a song called "Too Soon To Know," which they'd sung over station WBAL. I asked Deborah about this and she had no explanation for it. She said that they'd never recorded the song as a demo and probably wouldn't have sung it on the radio prior to it being formally recorded.

But that's not true; the Vibra-Naires did sing "It's Too Soon To Know" before it was waxed. Jay Bruder found the following blurb in the April 3, 1948 Baltimore Afro-American: "The Vibra-Naires quartet was heard on WCBM [680 AM] Tuesday [March 30], singing 'Too Soon To Know'. The group includes George Nelson, baritone; Richard Williams, bass; Sonny Tilghman, second tenor; Alex Sharpe [sic], 1st tenor; Spoons [???], guitar." So not only didn't they wait to sing the song, but Richard Williams was their bass over a month before they journeyed up to the Godfrey show.

Being a go-getter, Deborah took the Vibra-Naires' demos back to New York, to try to get some more opportunities for her group. Then fate stepped in; a chance meeting set the wheels turning. She and her mother went to Lindy's (a New York restaurant frequented by show business types and famous for its cheesecake); at the next table were Sid DeMay and Lee Tully. DeMay had once worked for National Records and had formerly been a partner with Jerry Blaine in Cosnat Record Distributors (about which more later). Lee Tully was a Jewish comedian who'd had a record called "Essen" (Eat!) on the Jubilee label (about which much more later). Deborah would one day write "Once In Every Lifetime" with Tully (it was recorded by Sunny Gale).

Being a go-getter, Deborah took the Vibra-Naires' demos back to New York, to try to get some more opportunities for her group. Then fate stepped in; a chance meeting set the wheels turning. She and her mother went to Lindy's (a New York restaurant frequented by show business types and famous for its cheesecake); at the next table were Sid DeMay and Lee Tully. DeMay had once worked for National Records and had formerly been a partner with Jerry Blaine in Cosnat Record Distributors (about which more later). Lee Tully was a Jewish comedian who'd had a record called "Essen" (Eat!) on the Jubilee label (about which much more later). Deborah would one day write "Once In Every Lifetime" with Tully (it was recorded by Sunny Gale).

They began talking and DeMay told her that her best bet would be to take her demos to either Jubilee or National. Deborah, realizing that National had the Ravens, decided to make her first stop Jubilee.

Jerry Blaine, of Jubilee Records, listened to the demos and saw the potential. He called in Sid DeMay and together they set up the It's A Natural label (at 220 West 42 Street [dial WI-7-6092]), just to handle the group. It's A Natural was distributed by Cosnat (no surprise there). I don't know why they didn't just put the group on Jubilee to begin with. It had been in existence for a while (as we'll see later), but was probably dormant at this time. Still, why go to the trouble of setting up a new label when you already have one? In spite of the new label, they used "JR" (Jubilee Records) prefixes on the masters.

Jerry Blaine, of Jubilee Records, listened to the demos and saw the potential. He called in Sid DeMay and together they set up the It's A Natural label (at 220 West 42 Street [dial WI-7-6092]), just to handle the group. It's A Natural was distributed by Cosnat (no surprise there). I don't know why they didn't just put the group on Jubilee to begin with. It had been in existence for a while (as we'll see later), but was probably dormant at this time. Still, why go to the trouble of setting up a new label when you already have one? In spite of the new label, they used "JR" (Jubilee Records) prefixes on the masters.

Now, with a recording contract, Deborah pulled out all the stops. The Vibra-Naires started intense practice on three tunes that she'd written ("there was a need to practice new stuff," said Deborah): "It's Too Soon To Know," "Barbra Lee," and "Tell Me So," as well as "At Night" (written by Clifton Morris, a friend of theirs), and two old standards: "I Cover The Waterfront" and their good-luck charm, "Exactly Like You." Rehearsals took place either in Deborah's apartment or at Johnny Reed's house.

Now, with a recording contract, Deborah pulled out all the stops. The Vibra-Naires started intense practice on three tunes that she'd written ("there was a need to practice new stuff," said Deborah): "It's Too Soon To Know," "Barbra Lee," and "Tell Me So," as well as "At Night" (written by Clifton Morris, a friend of theirs), and two old standards: "I Cover The Waterfront" and their good-luck charm, "Exactly Like You." Rehearsals took place either in Deborah's apartment or at Johnny Reed's house.

However, before the Vibra-Naires recorded, their name disappeared into history, to be replaced by the easier-to-spell "Orioles" (to honor the state bird of Maryland). They would soon be known as "The High-Flying Orioles."

However, before the Vibra-Naires recorded, their name disappeared into history, to be replaced by the easier-to-spell "Orioles" (to honor the state bird of Maryland). They would soon be known as "The High-Flying Orioles."

Sometime in July 1948, the Orioles had their first session, at which they recorded all six tunes that they'd been practicing: "At Night," "Barbra Lee,"

"It's Too Soon To Know," "Exactly Like You," "Tell Me So" (the version

with the humming bridge), and "I Cover The Waterfront." From the

beginning, the style of the Orioles was generally to have Sonny take the

lead, with George Nelson doing the second bridge. These were Sonny's

recollections of that first session:

This was a thrill for me. This was a brand new thrill—that I was going to New York to record, man! Wow! It was the greatest thing in my life 'cause in my school yearbook I said my aim was to become one of the greatest singers in show business.

We were scared, yeah we were scared. We were afraid we were going to do something wrong and it wouldn't come out right. But it all came out. We just all got together and Deborah said: "Look fellas, do it just like you did it at the house. Relax. And as soon as we get out, we're going to dinner."

Everything was done on one track. At that particular time, there were no musicians playing. [The musicians' union had gone out on strike on January 1, 1948 and technically wouldn't be back until the strike was settled on December 14. But as time went on, smaller labels ignored the strike more and more.] So we did our track without any music and later they put the music on.... There wasn't much music, just Tommy [Gaither, on guitar], Johnny [Reed, on bass], and a piano played by Sid Bass.

The first time I recorded I was anxious to hear the playbacks. I was very anxious to hear how I'd sound 'cause I'd always heard other people on records, but never myself. But this was exactly what I really wanted 'cause I like to hear what I'm doing when I sing. If I do any little vocal tricks, I can hear them and know they're getting over. I want to know the feeling is there when I'm singing. We did about four or five takes on "It's Too Soon To Know."

The Ink Spots had popularized the pattern of a "talking bass" on the

bridge of a song. So why did the Orioles use George's baritone

instead of Johnny's bass on the bridge? "George was a showman," said

Johnny. "Leave me back there hummin', that's my thing." Also, Sonny and

George worked out a little dance step which would bring George up to the

lead mike (the five of them only used two mikes), and Johnny was

prevented from doing this because of his full-size stand-up bass.

What was it like lugging that bass around? "You don't want to know," said Johnny.

"We did pretty good with it because they would help me with it... The

only way you can get a good sound is from a wooden bass, not a Fender. A

Fender's too mechanical. You'll always find a good bassist with an

upright bass.... [In the car] it takes up the room of a whole

person."

In July 1948, It's A Natural issued the first Orioles record: "It's Too Soon To Know"/"Barbra Lee." It was introduced on New York's WHOM by black DJ Willie Bryant and his white co-host Ray Carroll. When Jerry Blaine sent them the demo, he indicated that "Barbra Lee" was the A side. The next day, he asked Bryant how the reaction was to the tune. The answer was: "It was OK, but I'm going to flip it over tonight and see what happens." What happened is that listeners went crazy for "It's Too Soon To Know"; it started taking off almost immediately, selling 30,000 copies in its first week. By the time it had finished its

17-week run on the national R&B charts, it had risen to #1 (although

only for a single week). More surprising is that it peaked at #13 on the

Pop charts, something not many R&B songs did in those days. It was

such a big hit, in fact, that it was covered by the Ravens, the

Charioteers, the Deep River Boys, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Lee

Richardson, Savannah Churchill, Marion Robinson, Ronnie Deauville, and

the Jimmy Valentine Quintet. The Orioles' version was both a Cash

Box "Race Disk of the Week" and a Billboard Pick of the

Week.

In July 1948, It's A Natural issued the first Orioles record: "It's Too Soon To Know"/"Barbra Lee." It was introduced on New York's WHOM by black DJ Willie Bryant and his white co-host Ray Carroll. When Jerry Blaine sent them the demo, he indicated that "Barbra Lee" was the A side. The next day, he asked Bryant how the reaction was to the tune. The answer was: "It was OK, but I'm going to flip it over tonight and see what happens." What happened is that listeners went crazy for "It's Too Soon To Know"; it started taking off almost immediately, selling 30,000 copies in its first week. By the time it had finished its

17-week run on the national R&B charts, it had risen to #1 (although

only for a single week). More surprising is that it peaked at #13 on the

Pop charts, something not many R&B songs did in those days. It was

such a big hit, in fact, that it was covered by the Ravens, the

Charioteers, the Deep River Boys, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Lee

Richardson, Savannah Churchill, Marion Robinson, Ronnie Deauville, and

the Jimmy Valentine Quintet. The Orioles' version was both a Cash

Box "Race Disk of the Week" and a Billboard Pick of the

Week.

The record was reviewed in the August 21, 1948 issue of The Cash

Box, as follows:

A new vocal quintet on a new disk that speeds right into the top spot of the race disks this week and is really something to listen to. The 5 boys harmonizing on this tune, featuring a new, young tenor, Sonny Til, who spoons the lyrics of "Barbra Lee" to a fare-thee-well. It's great wax and it's got every possibility of hitting the top everywhere in the nation. What's more, as far as juke boxes are concerned, it's terrific from the standpoint it spins in only 2 minutes and 8 seconds. This means faster takes for juke box ops and, combined with a great tune, it should prove a winner from any angle. On the flip, "It's Too Soon To Know," the Orioles, once again featuring Sonny Til, produce another side of wax that's sure to set 'em battlin' as to which the best of the 2 sides on this platter. Both sides are set to spin themselves into ribbons on any location where they like their music soft, sweet and mellow. Grab a boxful and spread 'em around. [This was advice to the "ops," the people who owned the jukeboxes.] This disk's got "it."

[Keep in mind that reviews in Billboard and Cash Box weren't meant for the general public. They were for the owners of jukeboxes, record distributors, and anyone else who purchased directly from the manufacturers. The overriding consideration was "is this good enough to make money from." If an act had a big hit, that would influence a better review on the next record, because it was more likely to sell.]

And here's what Billboard said about "It's Too Soon To Know"

on September 4:

New label kicks off with fine quintet effort on a slow race ballad. Lead tenor shows fine lyric quality (85).

However "Barbra Lee" didn't fare so well:

Mediocre rhythm number doesn't show quartet to special advantage (70).

That same week, Billboard listed it as a Pick (along with Kay

Kyser's "Slow Boat To China").

The song catapulted the Orioles to the top in a "hot minute." Did

Johnny think the Orioles were something special? "It was just something

we all did and we liked doing it. We were just some guys out there

singing and hoping that it would fan into something, which it did." Did

it ever! Johnny found the success of "It's Too Soon to Know" shocking.

"It skyrocketed and scared me half to death. I didn't know what to do.

So I went and got a six-pack right away. No chaser."

How did Sonny see the market that the Orioles sold in?

I think we were aimed at the Negro market. I think that's the way it was because at the time you had the colored records, race records, and you know, it was a different thing. Like you have Soul music now. Soul music can be white or black. Then, the race music was black music by black artists. Although we were on the Negro market, we had quite a few white fans. I was surprised when we played mixed places. Then down south we played places with the white people upstairs and the colored people downstairs, or vice-versa. In the fifties, it was very nice to know we had mixed fans.

In late October 1948, Sid DeMay and Jerry Blaine (head of Cosnat Distributors) set up the Jubilee Music Company to publish songs from the It's A Natural catalog. Deborah Chessler immediately signed a 5-year contract with the Jubilee Music Company and the Orioles signed a 5-year contract with It's A Natural. The Jubilee Music Company didn't get the rights to "It's Too Soon To Know," however, since Deborah had already sold them to the Edwin H. Morris publishing house (six publishers had been bidding for it, said the trade papers). Also in October, the Orioles signed with the prestigious Gale Agency to do to their bookings. On October 22, they began a week at the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C.

And then, almost as soon as the It's A Natural label came into existence, it vanished. Both Sid DeMay and Jerry Blaine had worked for National Records and now their prior associates informed them that the name "Natural" was too close to "National" for comfort (the trades usually referred to it as "Natural," rather than "It's A Natural"). Thus, on October 23, DeMay announced that "all future releases of the Orioles ... will be on the Jubilee label" (located at 764 10th Avenue; just pick up your phone and dial PL-7-8140). The November 6 issue of Billboard reported that "Natural Records has changed its name to Jubilee Records to avoid confusion with the National label." In late October or early November, "It's Too Soon To Know" was re-released on the new Jubilee label, and it was listed in Billboard the following week. Just to provide some continuity, Jubilee's November ad for the Orioles' follow-up record had the dice at the top and the tag line "Follow up with another NATURAL." (Note that there was another Natural label in 1955, a short-lived subsidiary of Herald Records.)

And then, almost as soon as the It's A Natural label came into existence, it vanished. Both Sid DeMay and Jerry Blaine had worked for National Records and now their prior associates informed them that the name "Natural" was too close to "National" for comfort (the trades usually referred to it as "Natural," rather than "It's A Natural"). Thus, on October 23, DeMay announced that "all future releases of the Orioles ... will be on the Jubilee label" (located at 764 10th Avenue; just pick up your phone and dial PL-7-8140). The November 6 issue of Billboard reported that "Natural Records has changed its name to Jubilee Records to avoid confusion with the National label." In late October or early November, "It's Too Soon To Know" was re-released on the new Jubilee label, and it was listed in Billboard the following week. Just to provide some continuity, Jubilee's November ad for the Orioles' follow-up record had the dice at the top and the tag line "Follow up with another NATURAL." (Note that there was another Natural label in 1955, a short-lived subsidiary of Herald Records.)

Actually, the Jubilee label had been in existence since May of 1946. Herb Abramson, an A&R man for National Records, left them to continue his studies in dental school. As a sideline, he set up Jubilee Records, along with a couple of guys from Washington, D.C.: Ahmet Ertegun and Waxie Maxie Silverman (owner of the Quality Music record store). They immediately issued some gospel releases (on a 2500 series) by Bunk Johnson and his New Orleans Band, backing up Sister Ernestine Washington (how's that for an unusual combination?) and the Two Gospel Keys. When nothing much happened with those records, Ahmet and Waxie Maxie pulled out, but Herb hung on. He was soon joined by his old pal, Jerry Blaine, who had been the sales manager for National.

In the fall of 1947, after they'd issued some ethnic Jewish comedy discs by Lee Tully (on a 3500 series), Herb Abramson sold his share in Jubilee to partner Jerry Blaine (and rejoined Ahmet and Maxie to start Atlantic Records). It's unclear whether Blaine issued any sides during the next year.

In the fall of 1947, after they'd issued some ethnic Jewish comedy discs by Lee Tully (on a 3500 series), Herb Abramson sold his share in Jubilee to partner Jerry Blaine (and rejoined Ahmet and Maxie to start Atlantic Records). It's unclear whether Blaine issued any sides during the next year.

Jerry Blaine had been a bandleader in the late 30s, recording for Bluebird as "Jerry Blaine and His Streamline Rhythm." In the early days of World War 2, he seems to have been a test pilot, but by around 1945 he was working for National Records as their sales manager. At some point, he also became sales manager for Cosmo records and, out of the names of the two companies, he created Cosnat Distributors, sometime in 1946. [Although collectors revel in the output of Jubilee (and later Josie), Jerry Blaine's first love (and biggest source of income) was Cosnat. It would become the largest distributor in the United States (and, because he knew the right people, it would be the first distributor of Atlantic Records). His brothers, Ben and Elliot, ended up working at Cosnat, as well as his son, Steve.]

In the late 50s, Blaine would create Jay-Gee Records as an umbrella for all his record companies, including Jubilee and Josie. As profitable as Jubilee must have been, it seemed like Blaine was always trying to sell it. There were many blurbs in the trades over the years about the imminent sale of Jubilee. In July 1966, Cosnat was re-named "Jubilee Industries," and was finally sold, to the Viewlex Corporation, in June 1970 (prior to that, Jay-Gee Records had been spun off). Jerry Blaine officially retired as president and chairman of the board. Note that by this time, Jubilee had branched out. For example, part of the deal was for Jubilee Medical Supplies, which made disposable thermometers.

In the late 50s, Blaine would create Jay-Gee Records as an umbrella for all his record companies, including Jubilee and Josie. As profitable as Jubilee must have been, it seemed like Blaine was always trying to sell it. There were many blurbs in the trades over the years about the imminent sale of Jubilee. In July 1966, Cosnat was re-named "Jubilee Industries," and was finally sold, to the Viewlex Corporation, in June 1970 (prior to that, Jay-Gee Records had been spun off). Jerry Blaine officially retired as president and chairman of the board. Note that by this time, Jubilee had branched out. For example, part of the deal was for Jubilee Medical Supplies, which made disposable thermometers.

Although we tend to think of the Orioles as innovators, it's

important to remember that art doesn't exist in a vacuum. They, in turn,

had other artists influencing them. If you listen to Charles Brown (with

Johnny Moore's Three Blazers) singing "You Are My First Love," you can

hear how heavily Sonny was influenced by him. And Sonny said there were

others:

My favorite artist then was Nat "King" Cole, the King Cole Trio, when he was playing piano. There was a group called the Cats and the Fiddle who did "I Miss You So," which influenced us to record it. Then there were the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers. All those groups influenced us a lot. And Johnny Moore's Three Blazers too.

I've always been a believer in doing a song my way. I would love to do an album called "Sonny Til Sings Nat Cole." I wouldn't want anybody else to do all his tunes and make new hits and then the people would forget him. That's the only reason I'd like to do it close to Cole, 'cause that's the way I felt about him as a friend and an artist: a great man. Otherwise, I don't like to sing like nobody else. I appeared with Nat Cole on a couple of occasions, and it was always very nice. He was always a gentleman, a beautiful man.

As soon as the records began selling, the group started moving. They

played theaters up and down the East Coast and toured with some of the

leading names in Rhythm and Blues. Much has been written about the

rigors of travelling, and the constant one-nighters were grueling. But

manager Deborah Chessler was with them at all times, and

strangely, so was her mother. Said Johnny: "Mom Chessler was a heavy

lady, but she was right there with us. She'd go on one-nighters with us.

She didn't have nothing else to do, so she traveled with us."

As soon as the records began selling, the group started moving. They

played theaters up and down the East Coast and toured with some of the

leading names in Rhythm and Blues. Much has been written about the

rigors of travelling, and the constant one-nighters were grueling. But

manager Deborah Chessler was with them at all times, and

strangely, so was her mother. Said Johnny: "Mom Chessler was a heavy

lady, but she was right there with us. She'd go on one-nighters with us.

She didn't have nothing else to do, so she traveled with us."

On October 2, 1948, the Orioles were booked into the Howard Theatre in Washington, DC, along with Hal Singer. Right after this, they proudly began a week at Baltimore's Royal Theater, due to a sudden cancellation by an ailing Louis Jordan. They sang "It's Too Soon To Know," "Deacon Jones," "To Be To You," "Ain't She Pretty," and the old Cats and the Fiddle tune, "Stomp Stomp."

On October 2, 1948, the Orioles were booked into the Howard Theatre in Washington, DC, along with Hal Singer. Right after this, they proudly began a week at Baltimore's Royal Theater, due to a sudden cancellation by an ailing Louis Jordan. They sang "It's Too Soon To Know," "Deacon Jones," "To Be To You," "Ain't She Pretty," and the old Cats and the Fiddle tune, "Stomp Stomp."

The Orioles next session was held sometime in the fall of 1948. Considering that they cut eleven titles, it's reasonable to assume that there was more than one day involved. This time they laid down: "Two Party Line," "Lazy River Rolls By," a song with an unknown title (whose master has been lost), "I'm Losing Something I Never Had," "To Be To You," "It Seems So Long Ago," "(It's Gonna Be A) Lonely Christmas," "Deacon Jones," "Please Give My Heart A Break," "Tell Me So" (the version that ended up on the single, with George Nelson on the bridge), and "Dare To Dream."

In October, 1948, "It's Too Soon To Know" was named Record Of The Month by the Michigan Coin Machine Operators Association. This honor meant that the disc would have the number 1 spot on every jukebox in the state for the entire month of November.

Also in October, the Orioles were part of a benefit for the Damon Runyon Cancer Fund. With Ralph Cooper as emsee, it starred Joe Louis. Other acts were Bea Booze, the Betti Mays Swingtet, and the Avenue Playboys.

The Orioles second record was issued in November 1948: "To Be To

You," backed with the seasonal "(It's Gonna Be A) Lonely Christmas."

Here's how Cash Box reviewed the record on November 13, 1948:

The Orioles second record was issued in November 1948: "To Be To

You," backed with the seasonal "(It's Gonna Be A) Lonely Christmas."

Here's how Cash Box reviewed the record on November 13, 1948:

Make no mistake about this outfit—they're going right up the golden ladder of success, and fast! It's the Orioles, right on the heels of their smash success of "It's Too Soon To Know" coming back with another pair that should have phonos whirling like mad. The group has that extra something that puts them over the top. Wax, titled "To Be To You" and "Lonely Christmas" is loaded with stuff that makes for coin winners. Topside is the one that will draw immediate raves. The slow tender tones of beautiful harmony make for wonderful listening pleasure throughout. Ditty is enchanting and should captivate the fancy and attention of music fans from Maine to California. On the backside with another sweet hunk of wax, the group render some music aimed at the coming Xmas season. It's more slow, alluring vocalizing—of the sort you want to listen to time and again.

Billboard, on the other hand, didn't like "To Be To You" in

their December 4 review (although it received a rating only 3 points

lower than its predecessor):

Tune of Deborah Chessler of "Too Soon" fame doesn't measure up to its predecessor. Lyric is complex and Orioles are unable to project it clearly (82).

But the reviewer was happy with the flip (which makes no sense, since they both received the same rating):

Fine holiday fare, with the group doing a shining job with a pleasant sentimental ballad (82).

Like it or not, it became the Orioles second hit, climbing to #8 on

the R&B charts.

While their appearances had been booked by the Gale Agency for only a couple of months, that was about to change. Billy Shaw, who'd been a partner along with Moe and Tim Gale, decided to strike out on his own to set up Shaw Artists Corporation in January 1949. He took several of Gale's acts with him, including the Orioles, Hal Singer, and Wynonie Harris.

By January 28, 1949, "It's Too Soon To Know" was still the eighth

most played juke box race record, after seventeen weeks on the national

charts. The February 2 issue of Billboard had an ad for "It's Too

Soon To Know," which still touted it as a Natural record (complete with

the old address for It's A Natural). Also in January, since

"Lonely Christmas" sales had tapered off, Jubilee re-issued "To Be To

You," with "Dare To Dream" on the flip.

In February, Jubilee released "Please Give My Heart A Break"/"It Seems So Long Ago." Billboard reviewed them this way on February 12:

In February, Jubilee released "Please Give My Heart A Break"/"It Seems So Long Ago." Billboard reviewed them this way on February 12:

("Long"): The hot group turns out a good etching of a fair tune (75).

("Break"): Here is the formula—simple tune, note-bending delivery—that could give the group the follow-up to IT'S TOO SOON TO KNOW (85).

In early 1949, the Orioles appeared on at least two TV shows:

Eddie Condon's Floor Show on WNBC and Club Caravan on

WATV, hosted by Bill Cook, a New Jersey DJ, who would soon become Roy

Hamilton's manager.

The Orioles were a genuine phenomenon. The girls in the audiences

reacted to Sonny in the same way they'd reacted to Frank Sinatra in the

late 30's and the way they would later react to Elvis. There was

screaming, crying, fainting. And above all, an attempt to get a

"souvenir," like rings, cufflinks, any kind of jewelry, ripped right off

the performers. When they played the Apollo, Porto Rico (the backstage

manager), would say as they were leaving the theater: "You better bundle

up because they're out there." This was a signal to make sure your

wallet was protected. "They never got me," says Johnny Reed. "When they

took off after Sonny, I went the other way."

Unlike some other groups, the Orioles didn't try out their songs on

audiences before recording them. Johnny remembers: "Everything that we

sang professionally, Jerry Blaine had recorded back and on the shelf...

There's records coming out now that I forgot we even made 'cause in

those sessions he'd put down a couple of bottles of whiskey and some

hors d'oeuvres; it was really like a party. Little dumb us, we

just cut everything we could cut and he put it on the shelf. He sold

them or somebody sold them after he died."

April saw the release of the next Orioles record. It

was their version of Deborah Chessler's first commercially-recorded

song, "Tell Me So," backed with the Bullmoose Jackson tune from the

prior year, "Deacon Jones." They were reviewed by Billboard on

April 30:

April saw the release of the next Orioles record. It

was their version of Deborah Chessler's first commercially-recorded

song, "Tell Me So," backed with the Bullmoose Jackson tune from the

prior year, "Deacon Jones." They were reviewed by Billboard on

April 30:

("Deacon"): Zestful chanting of a revival take-off rhythm tune by the popular quintet (72).

("Tell"): One of those slow, easy torch ballads that lend themselves to the group's glissing, note-bending style. Could be an important platter in the race mart (83).

Could be. By the time "Tell Me So" had finished its 26-week run on

the R&B charts, it had reached #1 (although, like "It's Too Soon To

Know," for only a single week).

The Orioles' next sessions took place in the spring of 1949. Since

there are breaks in the master numbers, it's reasonable to assume that

these nine songs were done on three different days. (In the days when most

artists recorded four songs at a session, it's interesting that there

seemed to be no standard number for the Orioles.) The first five were:

"Moonlight," "Every Dog-Gone Time," "You're Gone," Rudolf Friml's

"Donkey Serenade" (led by George Nelson), and "It's A Cold Summer." Then

there were three others: "Is My Heart Wasting Time," "I Challenge Your

Kiss," and an unknown title whose master has been lost. The ninth song,

"A Kiss And A Rose," seems to have been recorded on its own.

The Orioles' next sessions took place in the spring of 1949. Since

there are breaks in the master numbers, it's reasonable to assume that

these nine songs were done on three different days. (In the days when most

artists recorded four songs at a session, it's interesting that there

seemed to be no standard number for the Orioles.) The first five were:

"Moonlight," "Every Dog-Gone Time," "You're Gone," Rudolf Friml's

"Donkey Serenade" (led by George Nelson), and "It's A Cold Summer." Then

there were three others: "Is My Heart Wasting Time," "I Challenge Your

Kiss," and an unknown title whose master has been lost. The ninth song,

"A Kiss And A Rose," seems to have been recorded on its own.

In June 1949, Jubilee issued "I Challenge Your Kiss," coupled with the old

Allan Jones hit from 1938, "Donkey Serenade." This was a song that

George Nelson particularly liked, and he got to lead it. It would be

the only Jubilee Orioles tune that wasn't led by Sonny. "I Challenge Your Kiss" was also released by the 4 Jacks on Allen in the same month; I'm not sure which was the original.

In June 1949, Jubilee issued "I Challenge Your Kiss," coupled with the old

Allan Jones hit from 1938, "Donkey Serenade." This was a song that

George Nelson particularly liked, and he got to lead it. It would be

the only Jubilee Orioles tune that wasn't led by Sonny. "I Challenge Your Kiss" was also released by the 4 Jacks on Allen in the same month; I'm not sure which was the original.

Cash Box really liked the Orioles. Here are the reviews of "I Challenge Your Kiss" and "Donkey Serenade":

("Challenge") Offering one of their most outstanding sides ever yet cut, the Orioles come up with a great winner in this recording. The ditty, a sweet, soft ballad, is offered in the Orioles' own inimitable vocal style, that has won them such wide acclaim throughout the nation. This disking is certain to find a top spot in any juke box. The vocal refrain of this side makes for easy listening and is most relaxing. Tempo of the tune is slow, with the group displaying their excellent vocal harmony in tones that add up to juke box coin. It's a platter that will find a tremendously favorable reception in most any location.

("Donkey") On the other end, the group comes up with one of the most unusual and novel arrangements of this famed tune ever yet heard.

And here's what Billboard had to say:

("Challenge"): The Orioles should have another winner in this hit ballad (82).

("Donkey"): The group's show-stopper makes for satisfactory wax (71).

"I Challenge Your Kiss" made the national charts for only a single week, where it stalled at #11.

In August, Jubilee released "A Kiss And A Rose"/"It's A Cold Summer." The former was a cover of a tune by Billy Williams and the Charioteers that had been released in March of that year (it had also been covered by the Ink Spots in April). Cash Box once again gave them great reviews. Note that the reviewer sometimes employs the British usage of a plural verb with a group noun ("the vocal group display"), instead of the more usual American usage of a singular verb ("the vocal group displays").

In August, Jubilee released "A Kiss And A Rose"/"It's A Cold Summer." The former was a cover of a tune by Billy Williams and the Charioteers that had been released in March of that year (it had also been covered by the Ink Spots in April). Cash Box once again gave them great reviews. Note that the reviewer sometimes employs the British usage of a plural verb with a group noun ("the vocal group display"), instead of the more usual American usage of a singular verb ("the vocal group displays").

("Kiss"): There's no stopping this group. Right on the heels of their smash disking of "I Challenge Your Kiss," the Orioles come up with another winner in this latest recording that should be one of their best and most popular. Titled "A Kiss And A Rose," the vocal group display an avalanche of grand vocal harmony on the side to set the stage for some torrid coin play. The ditty is a smart ballad that makes you wanna listen. It's great stuff the group offer and easy on the ears from the very first note. Slow infectious tempo added to the plush air surrounding the disk adds to the winning incentive found here.

("Summer"): The Orioles turn in another excellent performance to keep the platter sizzling hot. Ditty is a clever romantic ballad that should catch on and go. Music ops won't have to hesitate with this one—it's a winner—and a big one at that.

"A Kiss And A Rose" would go on to reach #12 (R&B), only

remaining on the charts for a scant two weeks.

Also in August (the week beginning the 12th), the Orioles appeared at

the Apollo Theater, along with Noro Morales and his Orchestra, Peg Leg

Bates, and Clarence Muse. They were back the week of August 26 (along with Wynonie Harris, the Dud Bascomb Orchestra, and Spider Bruce). This marked the first time in the Apollo's history that an act appeared again after only a one-week "layoff." On September 15, they kicked off a Southern tour with Hal Singer's Orchestra.

On September 25, 1949, the Orioles were back in the studio to record

"So Much" (Sonny's favorite of all the Orioles' songs), "Forgive And

Forget," and Frank Loesser's "What Are You Doing New Year's Eve."

In October, Jubilee released "So Much"/"Forgive And Forget."

"Forgive" was reviewed thusly by Cash Box:

By far one of the greatest platters this group have offered to date [that British construction again] is headed music ops' way in a blaze of glory. It's one of the nation's hottest vocal combos on tap to render a song that will sure catch on and go like wildfire in juke boxes thruout the land. The Orioles rendition of "Forgive And Forget" is a side that even looms to surpass the wide success this combo scored with "Am I Asking Too Much." [sic—This had been a #1 smash for Dinah Washington around the same time as "It's Too Soon To Know," although it's hard to see how the reviewer could have confused them.] This disk with the vocal group purring the lyrics of this wonderful melody is first rate harmony. It is a cinch to clinch with music ops and phono fans. The vocal beauty displayed on the side is hard to match—it's that good. Tempo is slow and infectious thruout with light dainty melody seeping thru the background.

The fans seemed to agree; "Forgive And Forget" rose to #5, and

remained on the R&B charts for nine weeks.

November 1949 saw the release of Frank Loesser's 1947 classic, "What

Are You Doing New Year's Eve." It was backed with a re-issue of "(It's

Gonna Be A) Lonely Christmas." The top side was on the national charts

for two weeks, peaking at #9; the flip (which had reached #8 the prior

year) made it to #5 this time, although it only charted for a single

week.

On December 23, the Orioles began a week at the Apollo Theater, along with

Dizzy Gillespie, Moke & Poke, and Pigmeat Markham. While they were

in town, they held another session on December 26, at which they only

recorded a single tune: "Would I Still Be The One In Your Heart"

(mislabeled, when released, as "Would You Still Be The One In My Heart").

It was issued in January, 1950, coupled with "Is My Heart Wasting Time."

The sides were reviewed by Billboard on February 11:

On December 23, the Orioles began a week at the Apollo Theater, along with

Dizzy Gillespie, Moke & Poke, and Pigmeat Markham. While they were

in town, they held another session on December 26, at which they only

recorded a single tune: "Would I Still Be The One In Your Heart"

(mislabeled, when released, as "Would You Still Be The One In My Heart").

It was issued in January, 1950, coupled with "Is My Heart Wasting Time."

The sides were reviewed by Billboard on February 11:

("Would"): A strong blues ballad gets an arresting sinuously-slow treatment from the group. Should be a hot side for The Orioles and tune should get attention from other R&B performers (85).

("Wasting"): Only passable in comparison with strong reverse side in this slow ballad (73).

Also in January, the Orioles appeared with Hal "Corn Bread" Singer,

the 3 Flames, and the Rimmer Sisters at Baltimore's Royal Theater. On

February 5, they were with Duke Ellington, Al Hibbler, Lu Elliott, and

Kay Davis at the Civic Opera House in Chicago.

It was back to the studios on February 17, 1950, when they cut some

sides using violins, an innovation in R&B music: "You Are My First

Love," "If It's To Be," "I Wonder When," and "Everything They Said Came

True." Why didn't it start a trend then (as the Platters would several

years later)? Sonny said: "We were the first group that recorded with

strings. That meant more musicians would have to be on the stage when we

appeared, and it got too expensive."

While they were in for that session, the Orioles reported to the Apollo

Theater, where they received a trophy from New York's disc jockeys

(presented to them by Willie Bryant, Ray Carroll, Phil Gordon, Ralph

Cooper, Bill Cook, and Harold Jackson). Dizzy Gillespie, Deborah

Chessler, and Jerry Blaine were in attendance. Later that month, they

headed down to Virginia to play the Town Club in Virginia Beach and the

USO Auditorium in Norfolk.

While they were in for that session, the Orioles reported to the Apollo

Theater, where they received a trophy from New York's disc jockeys

(presented to them by Willie Bryant, Ray Carroll, Phil Gordon, Ralph

Cooper, Bill Cook, and Harold Jackson). Dizzy Gillespie, Deborah

Chessler, and Jerry Blaine were in attendance. Later that month, they

headed down to Virginia to play the Town Club in Virginia Beach and the

USO Auditorium in Norfolk.

In March 1950, Jubilee issued "At Night" and "Every Dog-Gone Time."

They were reviewed by Billboard on April 8:

("Night"): Chalk up another hit for the high flying group. Tune is standout; group delivers one of their best jobs yet (85).

("Every"): Ordinary ballad is paled by flip. Lacks tension and mood created on overside (70).

On April 19, the Orioles and Amos Milburn began a series of

one-nighters in the south, kicking off at the City Auditorium in

Savannah, Georgia. They'd go on to appear at Durham (North Carolina),

Charleston (South Carolina), Pensacola (Florida), Jacksonville

(Florida), Atlanta (Georgia), and Monroe (Louisiana).

On May 7, 1950, they appeared at a dance at the Starlite Arena in

Baltimore. Later that month, on the 26th, they began a week's stay at

the Apollo, along with bandleader Buddy Rich. Whereas they once sang for

$15 apiece, they'd now be paid $5000 for the week (up from $500 the year

before). They'd soon be paid the same in the other big venues: the

Howard, the Royal, and the Earle.

On May 7, 1950, they appeared at a dance at the Starlite Arena in

Baltimore. Later that month, on the 26th, they began a week's stay at

the Apollo, along with bandleader Buddy Rich. Whereas they once sang for

$15 apiece, they'd now be paid $5000 for the week (up from $500 the year

before). They'd soon be paid the same in the other big venues: the

Howard, the Royal, and the Earle.

Before coming to the Apollo, they'd appeared on the Larry Shields

radio show in Savannah, Georgia (over WFRP). Shields had invited his

listeners up to the studio, and the kids ended up ripping the Orioles'

uniforms to shreds in order get souvenirs. The article went on to say

that, since their bags had already gone on to their next venue, the guys

had to borrow suits from a local tailor. However, this smacks of a press

agent with an over-active imagination: it's unlikely that anything was

"sent on ahead." Most probably, they had all the rest of their outfits

downstairs in their cars.

By May, the Jubilee offices had moved from 10th Avenue to their new home at 315 West 47th Street. This probably coincided with Sid DeMay leaving the firm to start up Uke Records (located down the block at 224 West 47th). Why he'd start an entire label to handle ukulele music in the 1950s is a question better left unanswered. In August, Sid would sell the master of Harry Martin playing "Basin Street Blues" on the ukulele to Jerry Blaine. In 1956, having seen the error of his ways, DeMay would become a partner in Flair-X Records.

Also in May, Jubilee released the beautiful "Moonlight," backed with "I Wonder When." Here's what Cash Box had to say about them on May 13:

Also in May, Jubilee released the beautiful "Moonlight," backed with "I Wonder When." Here's what Cash Box had to say about them on May 13:

Upper circle is a hot comer that looks as tho it may be one of the top ballads of the Summer season. "Moonlight" features the competent quintet turning in a sock arrangement with tremendous scope for a group harmony effort. Number itself is an artful engraving of a tender opus. Flip is a ballad featuring a deceptive male lead; "Moonlight" is our bet to happen very big.

But Billboard, on June 3, decided they liked it the other way around:

("Moonlight"): Ordinary ballad side in comparison with the standout flip job (71).

("Wonder"): Group does one of their top performances here on a promising torcher. Orking is rich, with full fiddle effects (85).

The Orioles didn't use much choreography in their act. As was pointed out

before, Sonny and George had a dip step that would bring George to the

lead mike (where Tommy Gaither and Sonny Til normally were), and take

Sonny to the group mike (with Alex Sharp and Johnny Reed). Sometimes

Alex would do some steps during a sax break.

The Orioles didn't use much choreography in their act. As was pointed out

before, Sonny and George had a dip step that would bring George to the

lead mike (where Tommy Gaither and Sonny Til normally were), and take

Sonny to the group mike (with Alex Sharp and Johnny Reed). Sometimes

Alex would do some steps during a sax break.

What Sonny did do was croon love ballads, making love to the

microphone. His crooning drove the girls wild. Bob Schiffman, son of the

owner of the Apollo Theater, recalled that when Sonny appeared, he would

be greeted by such expressions of undying love as "ride my alley,

Sonny." In fact, in an age when there was usually a fast "A" side and a

slow "B" side, of the Orioles' first twenty records, only four sides

were uptempo. This was one of the vital ingredients in the formula of

their success.

The Orioles went back to the studios on June 3, 1950 to record "I'd Rather Have You Under The Moon" and "We're Supposed To Be Through." Jubilee issued "Everything They Said Came True"/"You're Gone" in time to be reviewed by Cash Box on June 10:

The Orioles went back to the studios on June 3, 1950 to record "I'd Rather Have You Under The Moon" and "We're Supposed To Be Through." Jubilee issued "Everything They Said Came True"/"You're Gone" in time to be reviewed by Cash Box on June 10:

You can wrap up a great big bouquet for The Orioles right quick, for this latest etching by the group is by far and large the best thing they've done since "It's Too Soon To Know." Consistent winners that they are, the vocal combo step out in a new role on this pair that should cause a ton of tongue wagging in no time at all. Both ends of the platter are blue-ribbon winners. Top deck is a slow, tender ballad that has been around some.

On June 12, in Suffolk, Virginia, they kicked off a 30-day tour of

Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and

Alabama. In July, the Orioles appeared with the Paul Williams Band, at

the Maple Grove Inn in Devon, Pennsylvania. They were doing so well (and

making Jerry Blaine so much money), that Blaine presented them with a

new Cadillac when they played Asbury Park that month. It was reported

that he'd recently given the group a $50,000 royalty check on top of

that.

On June 12, in Suffolk, Virginia, they kicked off a 30-day tour of

Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and

Alabama. In July, the Orioles appeared with the Paul Williams Band, at

the Maple Grove Inn in Devon, Pennsylvania. They were doing so well (and

making Jerry Blaine so much money), that Blaine presented them with a

new Cadillac when they played Asbury Park that month. It was reported

that he'd recently given the group a $50,000 royalty check on top of

that.

The next session was held on August 18, 1950. The four tunes were: "I

Need You So," "Goodnight Irene," "I Cross My Fingers," and "Can't Seem

To Laugh Anymore." The next day, they returned to record Una Mae

Carlisle's "Walking By The River" and the Cats and the Fiddle's 1940

classic, "I Miss You So."

Four days later, they were at the Star Theater (in Akron, Ohio), as

the kick-off of a three-week swing through the south and midwest. Other

places they'd play on the tour included the Lyric (Lexington, Kentucky),

the National (Louisville, Kentucky), the Lincoln (Columbus, Ohio), the

Roosevelt (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), the State (Cincinnati, Ohio), the

Bijou (Nashville, Tennessee), and the Liberty (Chattanooga, Tennessee).

When they played the Lyric, some of the girls in the audience charged

the stage to get near their idols; the Orioles fled to their dressing

room, and this caused the postponement of the show for a half hour while

the stage was cleared.

Four days later, they were at the Star Theater (in Akron, Ohio), as

the kick-off of a three-week swing through the south and midwest. Other

places they'd play on the tour included the Lyric (Lexington, Kentucky),

the National (Louisville, Kentucky), the Lincoln (Columbus, Ohio), the

Roosevelt (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), the State (Cincinnati, Ohio), the

Bijou (Nashville, Tennessee), and the Liberty (Chattanooga, Tennessee).

When they played the Lyric, some of the girls in the audience charged

the stage to get near their idols; the Orioles fled to their dressing

room, and this caused the postponement of the show for a half hour while

the stage was cleared.

That same month, Jubilee released "I'd Rather Have You Under The

Moon," coupled with "We're Supposed To Be Through." They were reviewed

by Billboard on September 23:

("Moon"): Warblers do a Mills Brothers here as they double the tempo for second chorus. Ditty is attractive (81).

("Through"): The popular group gets off one of its usual slow note-benders on an okay torcher (78).

The September 1950 release was Leadbelly's "Goodnight Irene," backed

with Ivory Joe Hunter's "I Need You So." They both got good ratings the

week of October 4. On October 5, they began another week at the Apollo, along with the Treniers and the Sy Oliver Orchestra.

Then, on October 10, 1950, the Orioles returned to the

studio to record a couple of religious songs that could be released for

the Christmas season: "The Lord's Prayer" and "Oh Holy Night." Also in

October, Jubilee issued "I Cross My Fingers"/"Can't Seem To Laugh Any

More." The record was reviewed by Billboard on November 11:

Then, on October 10, 1950, the Orioles returned to the

studio to record a couple of religious songs that could be released for

the Christmas season: "The Lord's Prayer" and "Oh Holy Night." Also in

October, Jubilee issued "I Cross My Fingers"/"Can't Seem To Laugh Any

More." The record was reviewed by Billboard on November 11:

("Laugh"): Sock reading of the Johnny Parker ballad should score another winner for The Orioles (83).

("Cross"): Neat R&B treatment of this pop hit [a minor hit for both Bing Crosby and Perry Como in mid-1950] rounds out one of the best couplings the group has turned out (79).

Johnny Reed was one of the Orioles' designated drivers. He loved to drive in the 50s; still did in the 90s. But even the driver has to rest, and Tommy Gaither was at the wheel on November 5, 1950, when their car crashed into a drive-in restaurant, killing Tommy and injuring Johnny and George Nelson, who were removed unconscious from the wreckage. (Sonny and Alex, along with Deborah Chessler, were in another car.)

Tommy had taken a curve too fast and lost control of the car, which had

careened across the highway, rolling over three times before crashing

into the restaurant in the Essex section of Baltimore. They were on their

way home from a gig in Hempstead, New York and were going to spend

some time in Baltimore doing a little Christmas shopping before their next

appearance, at Turner's Arena in Washington, D.C. The two cars had been

traveling together, but Alex (who was driving Sonny's car at the time) lost

track of Tommy. Not knowing about the accident, Sonny, Alex and Deborah

went to their homes. When they learned about it, they all went to City

Hospital to identify Tommy and see George and Johnny.

Strangely, even with all the Orioles' success since their early days, the

newspaper accounts continued to state that they were formerly known as the

Vibranaires [sic].

Sonny recalled the loss that he felt at Tommy's death:

The most interesting thing in the life of the Orioles was a disheartening thing: when we had the accident and Tommy got killed. I've never been through anything like that. It was weird, because you were standing on a stage singing with a guy for years and all of a sudden he's dead in an automobile accident. And then you go back on the stage and start singing and look for this guy. He always stayed right next to me and I sorta depended on him. "Pal Of Mine" we cut right after that, and it was in honor of Tommy Gaither.

However, unbeknownst to the Orioles, their troubles were just beginning. Only a week after the crash, the Dominoes would record their first sides and the public would be introduced to Clyde McPhatter with "Do Something For Me," released in December. His was the voice that would dethrone Sonny Til's.

On their next engagement (at Turner's Arena), only Sonny and Alex were able to

perform as the Orioles. Sonny began singing "My Buddy," but couldn't finish it (Alex

did). Then they picked up two new members. Sonny remembered:

On their next engagement (at Turner's Arena), only Sonny and Alex were able to

perform as the Orioles. Sonny began singing "My Buddy," but couldn't finish it (Alex

did). Then they picked up two new members. Sonny remembered:

We were working in Philadelphia, the Earle Theater, with Duke Ellington, right after the accident in which Tommy was killed, and we auditioned [guitarist] Ralph Williams to do the show. We liked what he did. [Williams was added during the last week of November.] George and Johnny and Tommy were missing, so we had to add as many people as we could. Charlie Harris knew all the Orioles' songs on piano, so we hired him too. He was out of Philadelphia, and Ralph Williams was from St. Louis, by way of New York. Someone told him to get down there, 'cause the Orioles had had an accident and needed a guitar player. He fit in very well.

Ralph Williams was nicknamed "Oopie," probably from a habit of saying

"oopie doopie doo." He'd been part of a trio backing Martha Davis (on the

Jewel label) in 1948. The papers said that the new members of the Orioles were "D. Williams, a guitarist hailing from St. Louis, Mo. [another paper said

Chicago], formerly with the 4 Esquires in Hollywood [or maybe the '4

Black Cats and a Kitten'] and more recently head of his own trio in New

York City" and "Charles Harris, pianist of Philadelphia and Chester,

Pa., recently featured [with his 6-piece combo] over WCAU-TV,

Philadelphia [on the "Take Ten" show], is a temporary replacement for

Johnny Reed, bass player, who is recovering in Baltimore's City

Hospital." Actually, Harris became a permanent member of the group.

Ralph Williams usually only played guitar, but he would sing second

tenor (as had Tommy Gaither) when they needed an extra voice (he's heard

saying his trademark "oopie, doopie, doo" on the interchange in "How

Blind Can You Be"). Charlie Harris wasn't a singer, just an accompanist.

While Johnny Reed played on sessions (as had Tommy Gaither), Ralph

Williams and Charlie Harris usually didn't.

It didn't take George Nelson long to return, but Johnny Reed was out

for about three weeks. The Orioles were at the Earle Theater when Johnny

hobbled in, and was standing in the wings watching the show. Duke

Ellington spotted him and pulled him onstage, while Sonny announced his

return. The crowd went wild. Wendell Marshall, Duke's bass player gave Johnny his

bass. "I was on a cane at the time; I gave Wendell the cane and I went

on to play."

"The Lord's Prayer" and "Oh Holy Night" were released in November.

They were reviewed by Billboard on December 2:

("Night"): Group does a straight forward reverent job on the Christmas hymn (73).

("Prayer"): As with flip, a good Yule coupling for Orioles (75).

On November 26, they took time out from an engagement in Detroit (with Duke Ellington) to do a benefit show at the Starlight Ballroom in Baltimore for Tommy Gaither's widow and four children. It was arranged by Baltimore DJ (WBAL) Chuck Richards. That's when they introduced "Pal Of Mine," as a tribute to Tommy. They announced that it would be recorded at their next session (which wasn't true; two more sessions would go by first), along with "Tennessee Waltz" (which they never recorded at all).

Their next session was held on December 20, 1950, but they only

recorded a single side: "I Had To Leave Town." It was supposed to have

been issued as Jubilee 5061 (along with "If It's To Be," recorded back

in February), but two other songs were substituted at the last

minute.

In spite of the tragedy they'd just suffered, the Orioles were up to speed to play New York's prestigious Carnegie Hall on Friday, December 22. They were part of a lineup that starred bandleader John Kirby, who had the entire show broadcast over the Armed Forces Radio Service, as a holiday treat for servicemen, especially those in Korea. Others on the bill were Wilbur de Paris and His New Orleans All Stars and Juanita Hall. The MC for the evening was DJ Art Ford, of station WNEW. The playbill for the show has the Orioles singing a medley of their hit recordings: "It's Too Soon To Know," "Tell Me So," "Forgive And Forget," "What Are You Doing New Year's Eve," and "Can't Seem To Laugh Anymore." In addition, there was a tune that they seemed to have forgotten to record along the way: "I Gotta Gal 65, And I'm Just 23." This was a Timmie Rogers tune (recorded for Excelsior in 1945 as "I Got A Gal 65, And I'm Just 23") that Ralph "Oopie" Williams led. In truth, this was an oddball place for the Orioles to have played in 1950, and, according to Deborah Chessler, it was "not a packed house."

In spite of the tragedy they'd just suffered, the Orioles were up to speed to play New York's prestigious Carnegie Hall on Friday, December 22. They were part of a lineup that starred bandleader John Kirby, who had the entire show broadcast over the Armed Forces Radio Service, as a holiday treat for servicemen, especially those in Korea. Others on the bill were Wilbur de Paris and His New Orleans All Stars and Juanita Hall. The MC for the evening was DJ Art Ford, of station WNEW. The playbill for the show has the Orioles singing a medley of their hit recordings: "It's Too Soon To Know," "Tell Me So," "Forgive And Forget," "What Are You Doing New Year's Eve," and "Can't Seem To Laugh Anymore." In addition, there was a tune that they seemed to have forgotten to record along the way: "I Gotta Gal 65, And I'm Just 23." This was a Timmie Rogers tune (recorded for Excelsior in 1945 as "I Got A Gal 65, And I'm Just 23") that Ralph "Oopie" Williams led. In truth, this was an oddball place for the Orioles to have played in 1950, and, according to Deborah Chessler, it was "not a packed house."

On December 25, the Orioles played Convention Hall in Atlanta. Ten

percent of the group's earnings (matched by the promoter) was turned

over to Tommy Gaither's widow.

The touring continued to take a toll, as the April 7, 1951 edition of the Chicago Defender reported:

ORIOLES AGAIN AVOID TRAGEDY OF AUTO SMASH

Akron, Ohio - The singing Orioles narrowly averted a second tragic accident when the car in which three members of the popular singing group were traveling was sideswiped by a truck on a highway on the outskirts of this city.

Although the car was forced off the road, skilful handling of the wheel by Sonny Til, who was driving, saved the three boys from possible serious injury. Sonny's companions in the car were George Nelson and Alex Sharp.

It was just last November that the group's guitarist, Tommy Gaither, was killed and Nelson and Johnny Reed sustained injuries in an auto accident near Baltimore.

The local accident took place as the Orioles were en route to a one-night stand at East Market Gardens in Akron.

[Another crash occurred in May 1952, when their 1947 Cadillac had

a blowout while they were en route to a gig in Shreveport, Louisiana. The

car was totaled, but no one was hurt.]

While the car crashes were the worst thing that happened to the

Orioles on tour, an article by Sonny in a 1952 issue of Tan

Confessions (entitled "Why Women Go For Me") reveals other sources

of trouble. Several quotes will serve to illustrate:

One night at a dance in an eastern city. I stepped out to the microphone with my fellow Orioles. I opened my mouth to take the lead in Baby Please Don't Go. A pretty, teenaged girl pushed through the crowd about the stage, looked into my startled eyes, and fainted dead away. Ten minutes later, when she gained consciousness in a dressing room, she tried to commit suicide by slashing her wrists.... That almost turned out to be a fatal thing for me. Even though I had nothing to do with influencing her to leave home and follow the Orioles, I got blamed for it. The girl's mother threatened to report me to the FBI.... We finally managed to persuade her to get on the train and go back home. I sent our valet along to buy her a ticket and take her home. He had so much trouble with her that afterwards he told me: "I'm going to quit the Orioles if I have to put up with this." Afterwards, she said her mother had put her up to telling lies on me so they could sue me and get some money.

And:

Once in New York, one of my enthusiastic fans slipped off my finger one of the initialed diamond rings which the Jubilee Record Company gave each one of us when Oriole record sales first reached the million mark.

And:

We had a big function once for about 2000 members of our fan clubs in New York. We gave away ice cream, cake and Cokes. We had to go to the party in dungarees because we knew it would be real foolish to wear good clothes. As it was, the kids got so excited and wanted to thank us so violently that we had to sneak out to save our necks.

The same article reported on the togetherness of the Orioles:

We all sat down together and mapped out a plan which we hoped would help keep us going to the top.

"You're the leader, Sonny," the boys told me. What you say goes. Every group has to have a leader.

"Okay with me, fellows," I told them. "Only there's one condition. I'd like to be the leader of the Orioles. But I don't want to be the boss. I don't want to be a dictator. I want to see decisions made by all of us.