The Royals

By Marv Goldberg

Based on interviews with Charles Sutton

© 2000, 2009 by Marv Goldberg

Much has been written about the Midnighters, first of the Detroit supergroups, but relatively little has been told about their origins. Starting out as the Royals, there were half a dozen records before they had a hit, and a few more before they rose to the top. This is the story of their beginnings.

Says Charles Sutton: "All of my life I liked to sing, from when I was 10. I listened to the Mills Brothers on radio and records. In 1947 or 48, I started going to amateur shows. When the Orioles came out, that was something different; I started to sing like that."

In 1950, while at one of those countless amateur shows, he ran across some other singers who were looking to start a group and the Falcons, all from the East Side of Detroit, were born. In the beginning, they were: Charles Sutton (baritone lead), Henry Booth (tenor; an original member of the Serenaders, when they were in junior high school in the mid-40s), Freddie Pride (baritone), and Sonny Woods (bass). Sonny (whose first name was actually Ardra, although Charles says he never heard him called anything but "Sonny") had once been a valet for the Orioles, and therefore was "by association" less of an amateur

than the others. To round out the group, Alonzo Tucker was added as an arranger and songwriter. (Alonzo, who was much older than the others, was also an occasional guitarist, appearing onstage with them a few times. He'd been the vocalist, and probably guitarist, for Jimmy Milner's Blue Ribbon Band, which had recorded for Fortune in 1949.)

Their idols were the Orioles, the 5 Keys, and the Dominoes. They sang mostly other groups' songs, especially at the many amateur contests they entered. Their forte, as was the Orioles', was love ballads. About six months after they formed, Freddie Pride was drafted; before he left, he recommend a friend, baritone/tenor Lawson Smith. (Freddie Pride would turn up again in 1960, along with Sonny Woods, Roquel "Billy" Davis (of the Thrillers/5 Jets), and Henry Howard, in "Billy Davis & Legends", recording "Goodbye Jesse" on Peacock.)

Detroit's Paradise Theater held amateur contests every Tuesday night, in addition to the regular show that was booked for the week. On Tuesday, October 16, 1951, the Falcons entered, singing the 5 Keys' latest hit, "The Glory Of Love". They won first prize (the munificent sum of $25), but more important, they also won the admiration of Johnny Otis, whose band was headlining the Paradise's week-long bill. He told them they had beautiful voices and had everything necessary to make a hit record. He also told them that he'd like to manage them; if they'd sign a 1-year contract, he'd get them a recording deal with Federal Records. Federal was run by Ralph Bass, whom he'd worked with at Savoy. (This was an amazing break for the Falcons. While at the Paradise, Otis was actually hoping to see the Serenaders perform. However, he was too late; the Serenaders had appeared on the amateur show the week before. They were backstage, but the group Otis got to hear was the Falcons.)

The Falcons signed on the dotted line, and Otis was as good as his word. About a week later, Syd Nathan, president of King and Federal, called them and made the deal. He sent them a contract (which guaranteed them a "generous" one-half cent per record sold).

The Falcons signed on the dotted line, and Otis was as good as his word. About a week later, Syd Nathan, president of King and Federal, called them and made the deal. He sent them a contract (which guaranteed them a "generous" one-half cent per record sold).

A strange blurb in the November 17, 1951 Detroit Tribune: "The Falcons, local quartet, was slated to leave for NFC for recording date Wednesday. They are to cut their initial disc for the Mercury Waxery. Henry Booth, Lawson Smith, Charles Sutton and Sonny Woods - all local guys - compose the quartet." Mercury??? Where did that come from? And what's "NFC" mean?

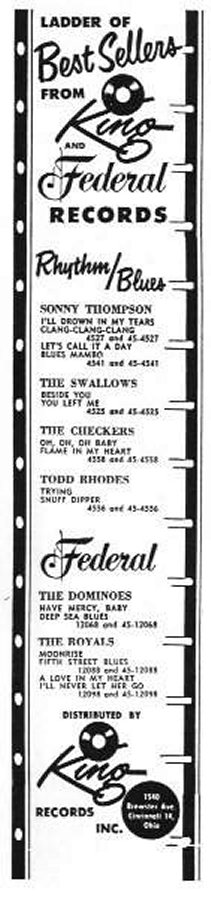

The only problem was that there was already a Falcons group around (Goldie Boots and the Falcons on Regent). A quick name change, and the Falcons became the Royals. On November 24, 1951, Federal records announced that it had signed the Royals, as well as several other acts, including saxman Gene Redd and Pete "Guitar" Lewis. (The same blurb said that Ralph Bass, Federal's a&r man, was finished with his work in New York, and was on his way to the West Coast to take charge of Federal's operations there.) The Royals were on their way.

A short while later, Nathan scheduled a recording session at Federal's headquarters in Cincinnati, for February 1952. However, once again Uncle Sam stepped in, drafting Lawson Smith. They called up Nathan, frantically asking him to move up the session so that Lawson could be on it. (This was not only doing a favor for a friend, it was a practical step; he knew all the arrangements they'd been practicing.) Nathan came through, rebooking the session for early January. He sent them $200 so they could catch a train down to Cincinnati, and put them up in a hotel. At this point Lawson had already been inducted, but he had about a week to go before leaving.

A short while later, Nathan scheduled a recording session at Federal's headquarters in Cincinnati, for February 1952. However, once again Uncle Sam stepped in, drafting Lawson Smith. They called up Nathan, frantically asking him to move up the session so that Lawson could be on it. (This was not only doing a favor for a friend, it was a practical step; he knew all the arrangements they'd been practicing.) Nathan came through, rebooking the session for early January. He sent them $200 so they could catch a train down to Cincinnati, and put them up in a hotel. At this point Lawson had already been inducted, but he had about a week to go before leaving.

While New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles labels, being in big cities, could have either a house band or at least a large pool of musicians that played on most of their sessions, Cincinnati wasn't like that. There weren't that many places for bands to perform, so they didn't hang around town much. Therefore, King/Federal sessions were scheduled for times when a King/Federal band was in town for a couple of days to record and/or appear. The Royals were therefore backed up by whoever was around, such as Todd Rhodes or Bill Doggett.

On January 8, 1952 the Royals stepped into the studio and recorded four sides: "I Know I Love You So" (led by Charles, with Henry on the second bridge), "Starting From Tonight" (led by Charles), "Every Beat Of My Heart" (led by Charles), and "All Night Long" (with the group singing as an ensemble).

Alonzo had written all the songs except "Every Beat Of My Heart", which was penned by Johnny Otis. The session was supervised by a&r man Henry Glover, who would be at all their sessions until "Work With Me Annie".

On January 8, 1952 the Royals stepped into the studio and recorded four sides: "I Know I Love You So" (led by Charles, with Henry on the second bridge), "Starting From Tonight" (led by Charles), "Every Beat Of My Heart" (led by Charles), and "All Night Long" (with the group singing as an ensemble).

Alonzo had written all the songs except "Every Beat Of My Heart", which was penned by Johnny Otis. The session was supervised by a&r man Henry Glover, who would be at all their sessions until "Work With Me Annie".

(Note that the lead singer with the beautiful smooth sound isn't Henry Booth, but Charles Sutton. Because of the success of Gladys Knight and the Pips' remake of "Every Beat Of My Heart" in 1961, King's DeLuxe subsidiary reissued it, with the label crediting "Henry Booth and the Midnighters". Possibly they just got it mixed up or possibly Henry was still with the Midnighters at that point. Whatever the reason, R&B fans have believed over the years that Henry was doing lead; he isn't.)

Although I said above that "All Night Long" was an ensemble effort, there are two discernable voices on it. The first belongs to Sonny Woods, doing some bass lines. The other belongs to another King artist: Wynonie Harris. He was at the King studio that day to record "Keep On Churning". Listening to the Royals session, and not

liking how the bridge to "All Night Long" was going, he jumped in to do it himself. (He threw in some overworked blues phrases, which lent an air of excitement to an otherwise dull song.) Charles admits that his timing wasn't right and he couldn't handle the bridge (remember, he liked to sing love ballads). While Alonzo Tucker normally didn't sing with the group (or even appear with them), he could do a pretty good Wynonie Harris imitation, and the few times that the Royals performed "All Night Long", he sang the bridge onstage.

A week after the session, Lawson Smith was gone. His replacement was John Kendricks, whom Sonny Woods knew (they both worked on the Ford assembly line). In fact all of the Royals worked for Ford, except Charles, who worked for Chrysler (you know what the big industry in Detroit was!). So whatever happened to John Kendricks? Well, he changed his name: you probably know him better as Hank Ballard.

A week after the session, Lawson Smith was gone. His replacement was John Kendricks, whom Sonny Woods knew (they both worked on the Ford assembly line). In fact all of the Royals worked for Ford, except Charles, who worked for Chrysler (you know what the big industry in Detroit was!). So whatever happened to John Kendricks? Well, he changed his name: you probably know him better as Hank Ballard.

On the way to hiring Hank, the February 2, 1952 Detroit Tribune had this in their music column: "If you are a first tenor and over 21 and an aspirant for the job, contact Sonny Woods at WO-5-5946."

While records could be released within days of a session, Federal didn't seem to be in a hurry to debut the Royals. "Every Beat Of My Heart" and "All Night Long" weren't released until March 1952. The record was reviewed the week of April 5, the same week as Ruth Brown's "5-10-15 Hours" was breaking big in New York, the Clovers' Middle Of The Night" and the Dominoes' "That's What You're Doing To Me" were pick hits in New Orleans, and Wini Brown's "Be Anything But Be Mine" was knocking them dead in Los Angeles.

Johnny Otis, their manager, got together with his sax player, Earl Warren, and lawyer Lou Lebish to come up with an offer for the Royals. They'd form a corporation (called L.O.W. -- as in Lebish, Otis, Warren) and pay the Royals a salary. The guys would be guaranteed $100 a week and all expenses would be taken care of. However, there were so many "small print" clauses (like the one that said they wouldn't be paid if they didn't work for 18 days) that the Royals turned it down. After all, it was dangerous for them; they were just starting, and not working much (besides, they all had "real" jobs at this point).

The Royals' next session took place on May 10, 1952, once again in Cincinnati. They recorded another four sides: "I'll Never Let Her Go" (led by an intense, raspy-voiced Hank), "Moonrise" (led by Charles), "A Love In My Heart" (led by Charles, with help from Henry Booth), and "Fifth Street Blues" (a song about Cincinnati, fronted by Henry Booth). "Moonrise", most people's favorite, was written by Alonzo (with the express purpose of making people "feel" a moonrise), and turned over to Federal's session arranger, who decided on the celesta and the echo effect. (A celesta is played like a piano, but instead of striking strings, the hammers strike metal plates suspended over wooden resonators.)

That same month Federal issued the second Royals' record: "Starting From Tonight" (my personal favorite), backed with "I Know I Love You So". It was reviewed the week of June 7, along with Tampa Red's "But I Forgive You", the 4 Blazes "Mary Jo", Shirley Haven & 4 Jacks' "Sure Cure For

The Blues", and the Charioteers' "I'm The World's Biggest Fool".

With some releases under their collective belt, the Royals started touring. They mostly played small-time gigs in Detroit, Toledo, and Columbus. While most of their material did well in Detroit, it would be a year before they had a national chart hit. The June 14 Detroit Tribune told of their wanderings: They'd played the Club DeLisa in Chicago (certainly not a small-time gig), Teen Town (Indianapolis), the Tropicana (Toledo), and the Unique (Flint).

In July, the third record: "Moonrise," backed with "Fifth Street Blues." It was reviewed the week of August 2 (with "Fifth Street Blues" getting the higher rating), along with Wynonie Harris' "Night Train," Charles Brown's "Without Your Love," the Griffin Brothers' "The Clock Song," and the intriguing Peppermint Harris ditty: "There's A Dead Cat On The Line."

In July, the third record: "Moonrise," backed with "Fifth Street Blues." It was reviewed the week of August 2 (with "Fifth Street Blues" getting the higher rating), along with Wynonie Harris' "Night Train," Charles Brown's "Without Your Love," the Griffin Brothers' "The Clock Song," and the intriguing Peppermint Harris ditty: "There's A Dead Cat On The Line."

Another two months went past, and when there was no real action, their fourth record was released in September. This time it was "A Love In My Heart" and "I'll Never Let Her Go." They were reviewed the week of September 27, when the tunes to watch were Amos Milburn's "Greyhound" (in Atlanta), the 5 Royales' "You Know I Know" and Lloyd Price's "Oooh-Oooh-Oooh" (in Richmond), and Todd Rhodes' "Trying" (in San Francisco).

Finally, the week of October 10, 1952, it was reported that "Moonrise", already three months old, was a territorial breakout in Philadelphia (along with the Du Droppers' "Cant Do Sixty No More").

On November 1, the Royals once again hit the ralis down to Cincinnati, where they recorded another four tunes: "The Shrine Of St. Cecilia" (led by Charles), "I Feel So Blue" and "Are You Forgetting" (both were led and written by Hank), and "What Did I Do" (another Alonzo Tucker tune, led by Charles).

"The Shrine Of St. Cecilia" was originally a Swedish hit in 1940. Brought to the U.S. and given new lyrics by Carroll Loveday, it had been a #3 hit for the Andrews Sisters in 1942. This would be the group's last session for six months.

Later that month, their fifth record: "Are You Forgetting" and "What Did I Do". It was reviewed the week of December 13, along with Little Walter's "Sad Hours", B.B. King's "Story From My Heart And Soul", Earl Bostic's "You Go To My Head", the Nic Nacs' (Robins) "Found Me A Sugar

Daddy", and Fat Man Matthews & the 4 Kittens' "When Boy Meets Girl".

On January 10, 1953, the Detroit Tribune reported:

Those four fabulous Royals will start on another one of their fame-seeking treks. The popular local quartet of Sonny Woods, Hank Ballard, Charles Sutton and Henry Booth will tramp through New York, Virginia and Kentucky on this jaunt.

Competition for the Royals with the waxing of "Don't Close Your Eyes" by a group who calls themselves the "Five Royales" [???] The local singing stars had to change their name from the Falcons in the Spring of '52 because of a similar incident.

The 5 Royales will now play a major role in the Royals' history.

Nothing much was happening with the Royals. They were turning out great records, they were getting good reviews, but people outside Detroit weren't buying. Therefore, in January 1953, when a promoter called, they got sucked into a situation they would have done better to avoid. James "Spizzy" Canfield (formerly part of a 40s comedy act called "Canfield & Lewis") had signed the 5 Royales, an up-and-coming Apollo group who hadn't yet had a national hit, to a 60-day package tour of the South. Then their first big hit ("Baby Don't Do It") broke, and the 5 Royales refused to go (finding more lucrative bookings elsewhere). Canfield had already done the advertising and bookings, and was now out his headlining group.

Nothing much was happening with the Royals. They were turning out great records, they were getting good reviews, but people outside Detroit weren't buying. Therefore, in January 1953, when a promoter called, they got sucked into a situation they would have done better to avoid. James "Spizzy" Canfield (formerly part of a 40s comedy act called "Canfield & Lewis") had signed the 5 Royales, an up-and-coming Apollo group who hadn't yet had a national hit, to a 60-day package tour of the South. Then their first big hit ("Baby Don't Do It") broke, and the 5 Royales refused to go (finding more lucrative bookings elsewhere). Canfield had already done the advertising and bookings, and was now out his headlining group.

Somehow he found out about the similar-sounding Royals, and decided to try his luck. He offered to pay them to take the 5 Royales' place for 60 days. When they finally met him, he confessed that "take the place of" meant "impersonate". The Royals reluctantly agreed, and were given one day to learn 5 Royales' songs and arrangements. Federal was never informed that they were going to do this. (Interestingly, the first record by the 5 Royales, "Too Much Of A Little Bit", had been released on Apollo as by the "Royals", back in October 1951.)

The tour started, featuring Anna Mae Winburn (and her all-girl orchestra), the Fou Chez dancers, and comedian Bobby Wallace. The 5 Royales' photo had been displayed in the theater lobbies for almost a month; Canfield simply removed them and stuck in the Royals' photo. This may have fooled some, but not many. The Royals simply didn't sound

anything like the 5 Royales, nor did they look like them. The entire charade lasted for about five nights. Finally, Carl Lebow (Apollo a&r man and 5 Royales' manager) and Ben Bart (head of the Universal Attractions booking agency) learned about it and got an injunction in Muscogee County, Georgia; it was served to the Royals while they were

onstage. (Anna Mae Winburn and her husband, who was the show's road manager, were jailed for a night for attempting to prevent the injunction from being served.) The Royals were enjoined from using the name "5 Royales" or "5 Royals," from using the other group's photo, or from inferring that they'd recorded "Baby Don't Do It."

More serious was that there was a hearing scheduled for June because of a $10,000 damage action against the Royals. Fortunately, Spizzy Canfield was the one who ended up paying; the Royals never had to go to court.

By now, their contract with Johnny Otis had expired, and they switched over to being managed by Al Green, who also handled many other Detroit acts over the years: Johnny Ray, Lavern Baker, the Royal Jokers, and Jackie Wilson were just a few. They weren't with him too long, however, before Syd Nathan talked them into being managed by a New York

lawyer. They ended up, even at the height of their career in 1954, earning $20 a night. Says Charles, "Al Green was a nice guy; we should have stayed with him."

In March 1953, Federal released the Royals' sixth record, coupling "The Shrine Of St. Cecilia" with "I Feel So Blue". It was reviewed the week of March 21, along with Shirley & Lee's "Shirley Come Back To Me", and the Jets' (Hollywood Flames) "Volcano". The pick of the week was Dean Barlow & the

Crickets' "You're Mine", reported to be strong in New York, Philadelphia, D.C., Baltimore, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The Royals hadn't scored big until now, but they were ready to roll!

On May 2, it was back to Cincinnati, for their fourth session. This time they only cut three sides: "Get It" (Hank and Sonny), "No It Ain't" (Hank), and "That's It", a fitting tune marking the last time Charles Sutton fronted a Royals' tune. By this time, Hank was turning the Royals into a blues vocal group. (Hank had always loved the blues, but he came from a very religious family; he'd be beaten just for humming a blues tune around the house. When he was 14, he ran away from home to live with relatives. It's a reasonably good bet that his family didn't appreciate the songs he sang with the Royals.)

"Get It" and "No It Ain't" were released in June, as the Royals' seventh record. They were reviewed the week of June 20, along with Sugar Ray Robinson's "Knock Him Down Whiskey", Wynonie Harris' "The Deacon Don't Like It", and the Jumping Jacks' "Do Let That Dream Come True". That same week, the Crickets "I'll Cry No More" was breaking in Philadelphia, Chicago, Cincinnati, and Buffalo, while the Flamingos' "If I Can't Have You" was

climbing in Philadelphia, Detroit, Cincinnati, Buffalo, and St. Louis.

Suddenly, "Get It" began to take off. The week of July 18, it was reported breaking out in Detroit. At the same time, the Clovers' "Good Lovin'" was moving in Cincinnati, and the Kings' "Why Oh Why" in Philadelphia. New releases that week were the Dominoes' "You Can't Keep A Good Man Down" (featuring the

first appearance of another Detroit singer, Jackie Wilson), and the Shadows' "No Use".

On July 25, 1953, it was reported that "Get It" was Federal's biggest seller for the week. This marked the first time that the Royals outsold Federal's monster attraction, the Dominoes. "Get It" had its biggest sales (to date) in Chicago, Detroit, and New Orleans. August 1 saw "Get It" listed as a pick of the week. It would eventually climb to #6 on the R&B charts, remaining for 9 weeks. It was the first time that the Royals had scored nationally. It wouldn't be the last.

With "Get It" doing just fine, Federal brought the Royals back into the studio on August 14 and 15 to record 4 more tunes. All led by Hank, they were: "Hello Miss Fine", "Someone Like You", "I Feel That-A-Way", and "That Woman". That same month, the group appeared at the Graystone in Detroit and the Trocavera Club in Columbus, Ohio.

September saw the release of the eighth Royals' disk: "I Feel That-A-Way" and "Hello Miss Fine". It was reviewed the week of October 24, along with the 5 Royales' "I Want To Thank You", the Wanderers' "Hey, Mae Ethel", the Blue Jays' "White Cliffs Of Dover", Otis Blackwell's "Daddy Rollin'

Stone", and Savannah Churchill's "Peace Of Mind". While it did well in Detroit, it failed to ride the wave of "Get It".

In December, the ninth record was issued: "That's It" and "Someone Like You". It was reviewed the week of December 19, along with Johnny Ace's "Saving My Love For You", Joe Turner's "TV Mama", the Hornets' "I Can't Believe", and the Diamonds' "Cherry". The pick of the week was Amos Milburn's "Good Good Whiskey". The record failed to chart. But it really didn't matter; the Royals were poised on the brink of R&B history (to coin a trite phrase).

One change had been made in the group: Alonzo Tucker was no longer their occasional guitarist. He now functioned solely as arranger, writer, and harmony coach. The new guitarist was Arthur Porter. (He would stay for about a year and then be replaced by Cal Green, who played with a Houston band that often backed up the group at shows. Arthur Porter was the "Eggie Porter" who played guitar behind Cliff Butler on his Favorite recording of "No Faith In You".)

A new year, 1954, and a new opportunity for the Royals. On January 14, they trudged back to Cincinnati for their sixth Federal recording session. This time was different. This time Federal a&r man Ralph Bass got involved. Strangely, up to now, the Royals had never met him; Syd Nathan, president of King/Federal, and a&r man Henry Glover were

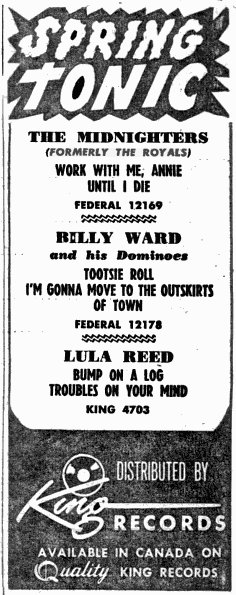

the ones who had supervised their sessions. (Remember, Bass had been busy with Federal's West Coast operations.) Bass had had an idea for a song lyric: "work with me". It had been going around and around in his mind, and now he brought it to the session. He and Hank sat down and worked on it until "Work With Me Annie" was born. Why "Annie"? Hank has said "It was just a good commercial name. You know, 'Annie Get Your Gun,' 'Little Orphan Annie'... It's just a catchy name. It could have been 'Work With Me Mary' or 'Work With Me Sue'." (This quote was from an interview done with Hank Ballard by Andrew Edelstein.) Note that with the tremendous results of this session, Ralph Bass took over and they would never again work with Henry Glover. Also done at that session were "Until I Die" and "Give It Up". All leads were by Hank.

February came and saw the release of the Royals tenth and last record: "Work With Me Annie" backed with "Until I Die". It was reviewed the week of February 27, along with the Moonglows' "Secret Love", the Hawks' "Joe The Grinder", the Robins' "I Made A Vow", the 5 C's' "Tell Me", and the Crystals' "My Love".

February came and saw the release of the Royals tenth and last record: "Work With Me Annie" backed with "Until I Die". It was reviewed the week of February 27, along with the Moonglows' "Secret Love", the Hawks' "Joe The Grinder", the Robins' "I Made A Vow", the 5 C's' "Tell Me", and the Crystals' "My Love".

"Work With Me Annie" started to take off almost immediately, and by the week of April 4, 1954, was a breakout record in Detroit, and a pick of the week in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Detroit, New York, Atlanta, Nashville, and St. Louis. Finally, "Work With Me Annie" made it to the top: #1 on the R&B charts (and stayed on those charts for 26 weeks!). In June, it even crossed over onto the pop charts for 3 weeks, climbing to #22. The amazing thing about all this, is that it was banned from most radio stations almost immediately! It was a solid juke box and record store hit.

What was the appeal of "Annie"? It had a simple, primitive, driving gospel-blues beat. It was "dirty". It was fun. It was raw, earthy R&B. You didn't hear Eddie Fisher or Dean Martin or Frank Sinatra singing to a girl "work with me" (whose meaning is best left to the imagination) or even "let's get it while the gettin' is good". Would Bing Crosby sing "Annie please don't cheat/ Give me all my meat"? Probably not. (Of course, pop lyrics aren't always as bland as they're made out to be. Cole Porter's "Let's Do It, Let's Fall In Love" begins: "Birds do it/ Bees do it/ Even educated fleas do it". What do they do? Well, they certainly don't fall in love as the lyrics would suggest.)

Actually, "Work With Me Annie" probably had more to do with introducing white teenagers to R&B than any other song. It wasn't the first crossover R&B hit: the Dominoes' "Sixty Minute Man" had crossed over in 1951 (reaching #17 on the pop charts, higher than "Annie" would reach) and the Crows' "Gee" crossed over in early 1954. Those were the cracks in the dike; "Annie" was the floodwaters let loose!

Lost in the uproar was the flip, "Until I Die", a pretty ballad featuring Hank. Listening to it, you can tell that Hank's idol was Clyde McPhatter. There's also the possibility that someone who bought the record and then flipped it over was James Brown; "Until I Die" sounds like it might have been part of the inspiration for "Please Please Please".

The song started two other trends: a series of "Annie" records (some by the Royals themselves) and a backlash in the DJ community against records with "questionable" lyrics. We'll examine those in a minute; now it's time to tell the story of the demise of the Royals.

An upheaval had been going on in the music industry. In April 1954, Federal Records announced that to avoid further confusion between their group and Apollo's 5 Royales, they were voluntarily changing the name of the Royals to the "Midnighters". This is probably hooey. The Royals were just beginning to emerge as hitmakers, but it's doubtful

that King would do this "voluntarily". What was really going on is that King was negotiating, behind the scenes, to steal the 5 Royales away from Apollo. If this could be made to happen (and it possibly had already happened by April, although they had done a session for Apollo on April 1), then King wouldn't want two of its groups to have similar names. Since the 5 Royales were hitmakers, guess who would have to change. On June 10, the 5 Royales had their first King session and in July, Apollo and King were locked in a screaming match over who actually had the group under contract. King won. By the way, remember Carl Lebow, a&r man for Apollo and manager of the 5

Royales? Well, by an amazing coincidence, Carl ended up as an a&r man at King. In April, Federal started pressing copies of "Work With Me Annie" as by the "Midnighters", and the Royals were history.

An upheaval had been going on in the music industry. In April 1954, Federal Records announced that to avoid further confusion between their group and Apollo's 5 Royales, they were voluntarily changing the name of the Royals to the "Midnighters". This is probably hooey. The Royals were just beginning to emerge as hitmakers, but it's doubtful

that King would do this "voluntarily". What was really going on is that King was negotiating, behind the scenes, to steal the 5 Royales away from Apollo. If this could be made to happen (and it possibly had already happened by April, although they had done a session for Apollo on April 1), then King wouldn't want two of its groups to have similar names. Since the 5 Royales were hitmakers, guess who would have to change. On June 10, the 5 Royales had their first King session and in July, Apollo and King were locked in a screaming match over who actually had the group under contract. King won. By the way, remember Carl Lebow, a&r man for Apollo and manager of the 5

Royales? Well, by an amazing coincidence, Carl ended up as an a&r man at King. In April, Federal started pressing copies of "Work With Me Annie" as by the "Midnighters", and the Royals were history.

Charles says that the name "Midnighters" was given to them, out of the blue, by Syd Nathan, who said "It would be a nice name for you guys." They always felt that he chose the name as being "black" (the same as "Ink Spots"). On the station wagon that they toured in, they had a clock painted on the sides with

the hands pointing to midnight. Did they care? Charles summed it up: "As long as we made money."

In February, prior to "Annie" becoming a hit, it was reported that a group of New York area DJs was organizing to stop playing "dirty" records. They planned to band together and not only not play the offending disks, but write the manufacturers involved to get them to stop. The organization finally got off the ground in late April, and was called "Metropolitan Disk Jockey Club and Association of Broadcasters". The charter members were Hal Jackson (WLIB), Bill Jenkins (WLIB), Jack Walker (WOV), Leigh Kamman (WOV), Bill Cook (WAAT), Tommy Smalls (WWRL), Phil Landwehr (WWRL), and Hal "Doc" Wade (WNJR). In August, Los Angeles parents started complaining about risqué lyrics. Local DJs were being cautious in playing disks from "certain" manufacturers. They didn't want parents to get the idea that all R&B music is dirty, because they'd stop their kids from buying it. In September, Peter Potter of KLAC (and host of CBS's "Juke Box Jury") said that the manufacturers and their a&r men were responsible, not the songwriters. He called much of R&B "not fit for radio broadcast". In October, WDIA in Memphis (with 50,000 watts) moved to ban all suggestive records, and so informed manufacturers. This included the whole of the "Annie" series.

Then the real obscenity began. The record companies started hypocritically stating how squeaky clean they were. Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler of Atlantic said "We are proud to stand on our reputation for having produced unobjectionable records." How soon they forgot the Drifters' "Honey Love" or the Clovers' "One Mint Julep", in which bass Harold Winley admits that he's "got six extra children from getting frisky") or Joe Turner's "Shake Rattle And Roll" with its "over the hill and way down underneath". Savoy's Herman Lubinsky (completely forgetting "Double Crossing Blues" by Little Esther & the Robins) said "We will not knowingly manufacture any double-entendre or suggestive records, even though we may lose sales." (So what did he think Bobby Nunn was talking about when he implied that Little Esther was a "lady bear"?) Then there was Bess Berman of Apollo, who stated: "I have never put out an off-color record, and I don't intend to start." It's amazing how the 5 Royales' "Laundromat Blues" and the Larks' "Little Side Car" were issued behind her back. How does she explain the 5 Royales' "Baby Don't Do It", which contains the plaintive cry "If you leave me pretty baby/ I'll have bread without no meat"? Guess she never listened.

At least Syd Nathan, whose King, Federal, and DeLuxe sides were, in total, raunchier than all the rest combined, had the decency not to bother to deny it. It was their policy to make money. If they felt that the record-buying public wanted these songs and would pay for them, they'd be issued. Let's face it, if a song is banned from the radio, doesn't it make you want to go out and buy it?

[AUTHOR'S NOTE: Originally, I had planned to end the article here, since the Royals no longer existed as such; the "Annie" session was the last that they did under that name. However, for reasons of spewing forth as much info as I can cram into this (which I hope is interesting to you), and because Charles Sutton was with them till

around the end of 1954, I decided to continue until the time he left.]

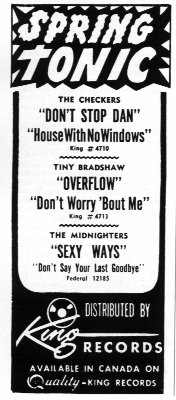

And now back to the Midnighters. In April, just when Federal knew they had something big on their hands, they got the group back into the studio (on the 26th) to cut the follow-up. They only did two songs: "Sexy Ways" and "Don't Say Your Last Goodbye". Also in April, Federal released another Midnighters' record: "Give It Up" and "That Woman". The record went nowhere, getting drowned in the wake of the "Annie" success.

"Sexy Ways" and "Don't Say Your Last Goodbye" were released in May, and were reviewed the week of June 5, 1954, along with the Drifters' "Honey Love", the Orioles' "Drowning Every Hope I Ever Had", the Moonglows "I Was Wrong", the Eagles' "Tryin' To Get To You", and the Deep River Boys' "Truthfully". That was some week! By the week of June 26, "Sexy Ways" was a pick of the week in Philadelphia, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Atlanta, St. Louis, Detroit, and Nashville. It would ride the R&B charts for 17 weeks, peaking at #2.

"Sexy Ways" and "Don't Say Your Last Goodbye" were released in May, and were reviewed the week of June 5, 1954, along with the Drifters' "Honey Love", the Orioles' "Drowning Every Hope I Ever Had", the Moonglows "I Was Wrong", the Eagles' "Tryin' To Get To You", and the Deep River Boys' "Truthfully". That was some week! By the week of June 26, "Sexy Ways" was a pick of the week in Philadelphia, Buffalo, Cincinnati, Atlanta, St. Louis, Detroit, and Nashville. It would ride the R&B charts for 17 weeks, peaking at #2.

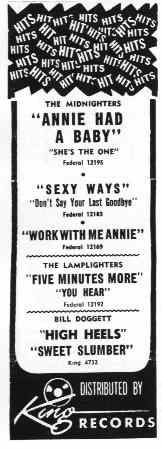

Of course, with all the furor over "Annie" and "Sexy Ways", the Midnighters were off touring extensively. While they were playing the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C., Federal decided to have them cut their own answer to "Work With Me Annie". Ralph Bass came to D.C. to work on the song with Hank (Syd Nathan and Henry Glover had written it). They rented a studio there, on July 30, and recorded "Annie Had A Baby". Why have them do it away from the Federal studios? Well, the story is cute (if nothing else). It seems that a couple of months before, a West Coast DJ (not named) had played "Work With Me Annie" and commented "If you think this one is great, you should hear their version of "Annie Had A Baby." Of course, orders started pouring in for the non-existent song. Therefore Nathan and Glover had to sit down and write it; therefore it was important that the Midnighters record it as quickly as possible. (This sounds very much like some public relations hack's idea of a great story. Charles can neither confirm nor deny it; they were just given the song to record.) The other song recorded that day (which would become the flip) was "She's The One".

Of course, with all the furor over "Annie" and "Sexy Ways", the Midnighters were off touring extensively. While they were playing the Howard Theater in Washington, D.C., Federal decided to have them cut their own answer to "Work With Me Annie". Ralph Bass came to D.C. to work on the song with Hank (Syd Nathan and Henry Glover had written it). They rented a studio there, on July 30, and recorded "Annie Had A Baby". Why have them do it away from the Federal studios? Well, the story is cute (if nothing else). It seems that a couple of months before, a West Coast DJ (not named) had played "Work With Me Annie" and commented "If you think this one is great, you should hear their version of "Annie Had A Baby." Of course, orders started pouring in for the non-existent song. Therefore Nathan and Glover had to sit down and write it; therefore it was important that the Midnighters record it as quickly as possible. (This sounds very much like some public relations hack's idea of a great story. Charles can neither confirm nor deny it; they were just given the song to record.) The other song recorded that day (which would become the flip) was "She's The One".

The record was issued in August, and reviewed the week of August 28, along with the Lamplighters' "Five Minutes Longer", the Strangers' "Hoping You'll Understand", the Penguins' "No There Ain't No News Today", the Cherokees' "Please Tell Me So", and Dorothy Logan & the Gems' "Since I Fell For You". The day after that, it was reported that the Midnighters got an injunction against WAAT's Bill Cook to stop him from promoting a group called the Midnighters Quartet, which was appearing at shows singing "Work With Me Annie".

The record was issued in August, and reviewed the week of August 28, along with the Lamplighters' "Five Minutes Longer", the Strangers' "Hoping You'll Understand", the Penguins' "No There Ain't No News Today", the Cherokees' "Please Tell Me So", and Dorothy Logan & the Gems' "Since I Fell For You". The day after that, it was reported that the Midnighters got an injunction against WAAT's Bill Cook to stop him from promoting a group called the Midnighters Quartet, which was appearing at shows singing "Work With Me Annie".

According to Syd Nathan, "Annie Had A Baby" was doing so well (by the end of August), that he was putting 16 presses to work 12 hours a day to turn out enough platters to meet the demand. Orders were pouring in in spite of the fact that most distributors had never even heard the song. The tune itself was almost a morality piece after

"Work With Me Annie". It tells the sad story of the aftermath: "Annie had a baby, she can't work no more." Our hero seems a bit deprived because "Every time we get to working/ She's got to stop and walk the baby 'cross the floor". He found out the hard way "That's what happens when the gettin' gets good".

"Annie Had A Baby" was the third monster hit for the Midnighters. It spent 14 weeks on the R&B charts, rising to #1 (it also made it to #23 on the pop charts). But more than that, this was the song that kicked off what's known as the "Annie" series. There are probably others, but a representative list looks like this:

Work With Me Annie - Midnighters - 2/54

Annie Had A Baby - Midnighters - 8/54

Annie Pulled A Hum-Bug - Midnights - 8/54

Annie's Answer - Hazel McCollum & El Dorados - 10/54

Mama Took The Baby - Lena Gordon & Sax Kari - 10/54

Annie's Aunt Fannie - Midnighters - 10/54

I'm The Father Of Annie's Baby - Danny Taylor - 11/54

My Name Ain't Annie - Linda Hayes & Platters - 11/54

Annie Kicked The Bucket - Nu-Tones - 12/54

The Wallflower (Roll With Me Henry) - Etta James - 12/54

Dance With Me Henry - Georgia Gibbs - 2/55 (#1 pop hit)

Hey, Henry! - Etta James - 4/55

Henry's Got Flat Feet - Midnighters - 5/55

Annie Met Henry - Champions - 8/55

Annie Met Henry - Cadets - 9/55

Let's Get Married - Shirley Gunter & Flairs - unreleased RPM - 55 (bass is Randy Jones)

Little Annie - Anna Belle Caesar - 1960

Work With Me Annie/Annie Had A Baby - Little Caesar & Romans - 1961

Annie Is Back - Little Richard - 4/64

Annie Don't Love Me No More - Hollywood Flames - 1965

There are loads of others without "Annie" or "Henry" in the title that might marginally qualify. Take "Framed" by the Robins. The policemen stop our poor hero and "They said 'Is your name Henry'/ I said 'Why sure'." Were Leiber and Stoller adding to the series, or was it just coincidence? Note that it has been rumored for at least 20 years that there was another Midnighters' "Annie" song, "Annie Had A Miscarriage", which was too raunchy for even Federal to release. Charles says it's just a myth; they never recorded anything by that name.

On September 23, the Midnighters were back in the studio. Another 4 songs; another "Annie". This time it was "Annie's Aunt Fannie", followed by "Stingy Little Thing", "Crazy Loving", and "Tell Them". This was their last session in 1954.

Later that month, they joined Todd Rhodes and his orchestra on a 90-day tour. (For some reason, Henry Booth didn't go on the tour with them; Lawson Smith returned to take his place.) They played the Oakland Auditorium, traveled around the Northwest, then hit Los Angeles on October 8-10 (playing Billy Berg's 5-4 Ballroom). From there they played

Tucson, Phoenix, and Albuquerque. Then it was Oklahoma City on October 16, where they appeared with the 5 Royales and the Tab Smith Orchestra. Then it was Dallas and Houston, and back to Los Angeles (and the 5-4 Ballroom again) on the 22-24. From there, they wound their way up the coast, reaching San Francisco by October 30.

Later that month, they joined Todd Rhodes and his orchestra on a 90-day tour. (For some reason, Henry Booth didn't go on the tour with them; Lawson Smith returned to take his place.) They played the Oakland Auditorium, traveled around the Northwest, then hit Los Angeles on October 8-10 (playing Billy Berg's 5-4 Ballroom). From there they played

Tucson, Phoenix, and Albuquerque. Then it was Oklahoma City on October 16, where they appeared with the 5 Royales and the Tab Smith Orchestra. Then it was Dallas and Houston, and back to Los Angeles (and the 5-4 Ballroom again) on the 22-24. From there, they wound their way up the coast, reaching San Francisco by October 30.

While they were in San Francisco, they got a call that a woman wanted to bring her 16-year-old daughter backstage to meet them. The daughter, Jamesetta Hawkins (soon to call herself "Etta James"), had written a song, based on "Work With Me Annie," called "Roll With Me Henry" (aka "The Wallflower"). She wanted the Midnighters to hear it and give it their blessing, which they did. Who knows, "Work With Me Annie" was off the charts by this time, maybe a similar record could help place it back there.

In October 1954, "Annie's Aunt Fannie" and "Crazy Loving" were released. They were reviewed the week of October 30, at the same time as the Lamplighters' "Yum Yum", the Rivileers' "Eternal Love", the Strangers' "Drop Down To My Place", the 5 Jets' "Crazy Chicken", the Ramblers'

"Vadunt-Un-Va-Da Song", and the 5 Dukes Of Rhythm's "Soft Sweet And Really Fine".

In October 1954, "Annie's Aunt Fannie" and "Crazy Loving" were released. They were reviewed the week of October 30, at the same time as the Lamplighters' "Yum Yum", the Rivileers' "Eternal Love", the Strangers' "Drop Down To My Place", the 5 Jets' "Crazy Chicken", the Ramblers'

"Vadunt-Un-Va-Da Song", and the 5 Dukes Of Rhythm's "Soft Sweet And Really Fine".

"Annie's Aunt Fannie" was a lame follow-up to "Annie Had A Baby", and actually would have made more sense (assuming any sense has to be made out of all this) if it had come before that song. It tells of Annie's aunt, who always seems to be around ("she's in my way ... how can I play"). Well, where did she

come from? He seems to have had no trouble "playing" before!

Also the week of October 30, "She's The One" was a breakout in New Orleans. Federal decided to play it smart and re-release "She's The One" (in December) when they found that DJs wanted to play it, but hesitated because it was the flip of "Annie Had A Baby". Just so they would take it seriously, Federal put the old Royals' tune, "Moonrise", as the new flip (they "updated" it slightly by overdubbing a guitar on top of the original).

On November 4, Louis Jordan held a benefit Show Of Stars at the Trianon Ballroom in Chicago. One of the featured acts was the Midnighters.

The week of November 13, 1954, "Annie's Aunt Fannie" was a pick of the week in Detroit, Buffalo, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Nashville, and Cincinnati (another pick that week was "Earth Angel" by the Penguins). In spite of this, it wasn't as big a hit as the previous two "Annies", only making the national R&B charts for a single week (at #10).

Never letting any grass grow under their pressing plants, Federal released "Stingy Little Thing" and "Tell Them" in November. They were reviewed the week of December 11, along with the Charms' "Mambo, Sh-Mambo", the Harptones' "Since I Fell For You", the Feathers' "Johnny Darling", the Bees'

"Get Away Baby", and the Mello Drops "When I Grow Too Old To Dream".

At the end of October, while the Midnighters were on the Todd Rhodes tour, Charles Sutton noticed something wrong with his voice: he couldn't hit certain notes and his throat began to hurt. He went to a doctor and was told that he had a tumor on his left vocal cord. He left the group in order to have it removed (fortunately it turned out to be benign). Henry Booth, who hadn't come on the tour in the first place, was persuaded to take Charles' place. Charles was forbidden to talk (let alone sing) for three months; he communicated by writing.

At the end of October, while the Midnighters were on the Todd Rhodes tour, Charles Sutton noticed something wrong with his voice: he couldn't hit certain notes and his throat began to hurt. He went to a doctor and was told that he had a tumor on his left vocal cord. He left the group in order to have it removed (fortunately it turned out to be benign). Henry Booth, who hadn't come on the tour in the first place, was persuaded to take Charles' place. Charles was forbidden to talk (let alone sing) for three months; he communicated by writing.

When Charles was finally better, he was, of course, eager to rejoin the group. But it didn't happen that way. They had a new manager, who told him that the group didn't want him back (the official line was that they'd worked out a lot of new dance routines which would take him too long to learn). He was given a few thousand dollars to quietly fade away.

When Charles was finally better, he was, of course, eager to rejoin the group. But it didn't happen that way. They had a new manager, who told him that the group didn't want him back (the official line was that they'd worked out a lot of new dance routines which would take him too long to learn). He was given a few thousand dollars to quietly fade away.

Of course, the Midnighters didn't quietly fade away. Although the hits stopped coming for a few years, they hung in there. Then, there was that little matter of "The Twist", released on King in December 1958 (this was the point when they were switched to the parent King label). As I wrote in my Spaniels article:

Of course, the Midnighters didn't quietly fade away. Although the hits stopped coming for a few years, they hung in there. Then, there was that little matter of "The Twist", released on King in December 1958 (this was the point when they were switched to the parent King label). As I wrote in my Spaniels article:

[... The Spaniels] were approached by a couple of members of the Sensational Nightingales gospel group. They'd written a song called "The Twist," but because of its suggestive lyrics, the Nightingales certainly couldn't record it. They'd already offered it to Little Joe Cook and the Thrillers, but had been turned down. The Spaniels took the song to Vee-Jay to see if there was any interest. Vee-Jay actually had the Spaniels record it, but decided that it wasn't their style, so it was never released. [It was probably more in the realm of a demo, since Vee-Jay never recorded it in their master book.]

However, the Nightingales kept trying to have their song recorded. Finally, in Miami, they found the perfect vehicle: the Midnighters. According to guitarist Cal Green, Hank Ballard liked it and the group made a demo which they sent off to, coincidentally, Vee-Jay (along with a tune called "I'll Pray For You"). Hank was sure that their King/Federal contract was about to expire and decided to give the Chicago company a try. Vee-Jay probably would have released it, but Syd Nathan informed the Brackens [owners of Vee-Jay] that he had picked up the Midnighters' option and they were still recording for him. Therefore, the original (and very different) recording of "The Twist" was kept hidden away until it appeared on a 1993 Vee-Jay CD.

After "The Twist", there was a string of hits for the Midnighters: "The Coffee Grind," "Finger Poppin' Time," "Let's Go, Let's Go, Let's Go," "The Hoochi Coochi Coo," "Let's Go Again," "The Continental Walk," "The Switch-A-Roo," "The Float," "Keep On Dancing," and "Do You Know How To Twist." With many personnel changes, Hank kept them going into the mid-1970s.

Meanwhile, not being content to just sit around, Charles got together with tenor Stanley Mitchell to form the Tornados. The other members were William Weatherspoon (tenor) and Ben Knight (bass; he'd been with the Imperials

on Great Lakes). Alonzo Tucker became their manager (he had broken off with the Midnighters at the same time that Charles had gotten ill). Sometime in 1956, Tucker got them a recording session for Chicago's Chess Records. A single record was released, in December 1956: "Four O'Clock In The Morning", backed with "Would

You - Could You". Although it was played on Michigan stations, it promptly went nowhere.

Note that at some point in 1956, Charles, along with Roquel "Billy" Davis

(of the 5 Jets) and Harry Pratt wrote "See Saw" for the Moonglows.

In all of 1957 the Tornados weren't called back to do another session. Finally, in 1958, feeling that Alonzo wasn't taking care of their business, they went to see Phil Chess themselves. It seemed like the right thing to have done: it got them another session. Sometime in 1958, they recorded some more sides, but after getting their hopes up, Chess never released any of them!

In 1959, they did some recording for Robert West, who owned a host of small Detroit labels (like Lu-Pine and Flick, on which he recorded the Falcons). This one was called Bumble Bee, and it had Charles' old Royals/Midnighters buddy, Sonny Woods as a&r man. They cut a couple of sides for West. One was "Love In Your Life", a ballad with

a beat. It owes something to Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters, and a bit to the Impressions. It was penned by Charles, and Robert Spencer, a baritone who was a utility fill-in for the Tornados whenever someone couldn't appear. The flip was "Geni [sic] In The Jug" (written by Charles and William Weatherspoon), in which the guy who rubs the lamp asks for a van so that he can bring Rock 'n' Roll all over. It names various artists, and says "and don't forget, we'll be there too".

In 1959, they did some recording for Robert West, who owned a host of small Detroit labels (like Lu-Pine and Flick, on which he recorded the Falcons). This one was called Bumble Bee, and it had Charles' old Royals/Midnighters buddy, Sonny Woods as a&r man. They cut a couple of sides for West. One was "Love In Your Life", a ballad with

a beat. It owes something to Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters, and a bit to the Impressions. It was penned by Charles, and Robert Spencer, a baritone who was a utility fill-in for the Tornados whenever someone couldn't appear. The flip was "Geni [sic] In The Jug" (written by Charles and William Weatherspoon), in which the guy who rubs the lamp asks for a van so that he can bring Rock 'n' Roll all over. It names various artists, and says "and don't forget, we'll be there too".

When that record failed to take off, Charles left and gave up singing, going back to working for Chrysler, from which he is now retired.

And that's the story of Charles Sutton and the Royals. I've gone a bit further than I'd originally intended, but it now covers the first three years of the group's Federal history. It's really a shame that the ballads the Royals first started with couldn't have done better commercially, but they more than made up for that once they met "Annie". Hank Ballard died on March 2, 2003 at the age of 75. In 2005, only Charles Sutton and Lawson Smith are still with us.

And that's the story of Charles Sutton and the Royals. I've gone a bit further than I'd originally intended, but it now covers the first three years of the group's Federal history. It's really a shame that the ballads the Royals first started with couldn't have done better commercially, but they more than made up for that once they met "Annie". Hank Ballard died on March 2, 2003 at the age of 75. In 2005, only Charles Sutton and Lawson Smith are still with us.

The ads appeared in various volumes of First Pressings, and are used by permission of Galen Gart. Special thanks to George

Moonoogian.

FEDERAL (the Royals)

12064 Every Beat Of My Heart (CS)/All Night Long (ALL/SW/WH) - 3/52

12077 Starting From Tonight (CS)/I Know I Love You So (CS/HBO) - 5/52

12088 Moonrise (CS)/Fifth Street Blues (HBO) - 7/52

12098 A Love In My Heart (CS/HBO)/I'll Never Let Her Go (HB) - 9/52

12113 Are You Forgetting (HB)/What Did I Do (CS) - 11/52

12121 The Shrine Of St. Cecilia (CS)/I Feel So Blue (HB) - 3/53

12133 Get It (HB/SW)/No It Ain't (HB) - 6/53

12150 Hello Miss Fine (HB)/I Feel That-A-Way (HB) - 9/53

12160 That's It (CS)/Someone Like You (HB) - 12/53

12169 Work With Me Annie (HB)/Until I Die (HB) - 2/54

FEDERAL (the Midnighters)

12169 Work With Me Annie (HB)/Until I Die (HB) - 4/54

12177 Give It Up (HB)/That Woman (HB) - 4/54

12185 Sexy Ways (HB)/Don't Say Your Last Goodbye (HB) - 5/54

12195 Annie Had A Baby (HB)/She's The One (HB) - 8/54

12200 Annie's Aunt Fannie (HB)/Crazy Loving (HB) - 10/54

12202 Stingy Little Thing (HB)/Tell Them (HB) - 11/54

12205 She's The One (HB)/Moonrise (CS) - 12/54

DELUXE (a King subsidiary; credited to Henry Booth & the Midnighters)

6190 Every Beat Of My Heart (CS)/Starting From Tonight (CS) - 4/61

LEADS:

CS = Charles Sutton; HB = Hank Ballard; SW = Sonny Woods; WH = Wynonie Harris; HBO = Henry Booth