The 3 Chocolateers

By Marv Goldberg

© 2014 by Marv Goldberg

Like the Harlem Highlanders, the Chocolateers (usually billed as the "Three Chocolateers") were primarily a visual act. Their routines would not have translated all that well to recordings, and in consequence they did almost none. However, in the past couple of weeks, I had occasion to listen to "Bartender Blues" a few times, and decided I wanted to know more about the group. It turns out that there's a wealth of information, but little real knowledge. The group was around from at least 1934 and was still trying to perform in the early 1960s. There don't seem to have been that many members of the group, but they came, and went, and returned in a bewildering fashion. (I'm sure there were some whose names I haven't encountered.) If their bookings are any indication (and they are), the group was immensely popular.

If the 3 Chocolateers are remembered at all, it's for their rendition of "Peckin'". This was originally an instrumental, written by bandleader Ben Pollack and his trumpeter at the time, Harry James. The "Chocs" worked up a routine for it that became so successful that they were hired to reprise it in the movie "New Faces Of 1937".

Before we begin, let's get some of the other Chocolateers out of the way. None of these has anything to do with the "Peckin'" group (and the list isn't exhaustive).

The story of the Chocolateers can be traced back to the Gibson family. Bethel Gibson, Sr. ran "Gibson's Minstrels" and "Gibson's Chocolate Revue", which played the Elmont Theater in Pittsburgh in November 1925. Two of the standout members of the act were Albert (12) and Corrine Gibson ("a pair of juvenile wonders"; they had earlier appeared as "Baby Corrine Gibson and Baby Albert"). By September 1926, Bethel Gibson's "Chocolate Box Revue Company" was appearing at Memorial Hall in Columbus, Ohio. The big star was Albert, reviewed by the Afro-American (June 23, 1928) like this: "Al is something of an artist despite his tender age [he'd have just turned 15]. The youngster swings into taps, eccentric [out of the ordinary dancing] and Russian with a freedom and naturalness that forces the customers to cheer him lustily...." Another sibling was Dixie Gibson, called the "screaming child personality" or "the personality child". In 1935 (aged around 4), she'd be part of Herman Whaley's Harlemaniacs, and in the mid-40s, a comedian (or "comedienne", as they were called then).

The story of the Chocolateers can be traced back to the Gibson family. Bethel Gibson, Sr. ran "Gibson's Minstrels" and "Gibson's Chocolate Revue", which played the Elmont Theater in Pittsburgh in November 1925. Two of the standout members of the act were Albert (12) and Corrine Gibson ("a pair of juvenile wonders"; they had earlier appeared as "Baby Corrine Gibson and Baby Albert"). By September 1926, Bethel Gibson's "Chocolate Box Revue Company" was appearing at Memorial Hall in Columbus, Ohio. The big star was Albert, reviewed by the Afro-American (June 23, 1928) like this: "Al is something of an artist despite his tender age [he'd have just turned 15]. The youngster swings into taps, eccentric [out of the ordinary dancing] and Russian with a freedom and naturalness that forces the customers to cheer him lustily...." Another sibling was Dixie Gibson, called the "screaming child personality" or "the personality child". In 1935 (aged around 4), she'd be part of Herman Whaley's Harlemaniacs, and in the mid-40s, a comedian (or "comedienne", as they were called then).

The "Bethel Gibson family" became part of the touring Olsen & Johnson company in 1932. In January 1933, Bethel was part of the cast of "Change Your Luck" at the Burbank Theater (he's referred to as "the famous head of the famous 'Gibson family of five' last year with Olsen and Johnson on nation-wide R.K.O. circuit").

Playing on the success of the 1932 movie "The Big Broadcast", Hollywood decided to do a follow-up, called "The Little Broadcast", using child entertainers. Two of those being considered for the film were Dixie and Bethel (Jr.) Gibson. "The Little Broadcast" became the working title for an "Our Gang" comedy that was released in 1934 as "Mike Fright", but Dixie and Bethel weren't included in the cast.

The Three Chocolateers first appear in print in the August 1, 1933 San Francisco Examiner, in its review of the show at the Capitol Theater. It said: "the three 'Chocolateers' demonstrate that they are no ordinary trio of tap dancers." They were part of the "Change Your Luck" company, which was presenting a revue called "Shuffle Along". It then spent a week at the Music Box in Tacoma, a week at the Vancouver Theater (Vancouver, British Columbia), and a day (September 27) at the Nanaimo (British Columbia)'s Capitol Theater.

The Three Chocolateers first appear in print in the August 1, 1933 San Francisco Examiner, in its review of the show at the Capitol Theater. It said: "the three 'Chocolateers' demonstrate that they are no ordinary trio of tap dancers." They were part of the "Change Your Luck" company, which was presenting a revue called "Shuffle Along". It then spent a week at the Music Box in Tacoma, a week at the Vancouver Theater (Vancouver, British Columbia), and a day (September 27) at the Nanaimo (British Columbia)'s Capitol Theater.

A December 16, 1933 ad for "Change Your Luck", at the World Theater (Kearney, Nebraska) said it featured the 3 Chocolateers.

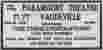

They next appear in the November 10, 1933 Helena Montana Herald-Record's review of that show, which had been at the Shrine Auditorium the day before. All it said of them was "The Three Chocolateers presented some novel and fast-stepping dances." Their first mention in an ad, was one appearing in the February 22, 1934 Seattle Northwest Enterprise. They ("Fast Dixie Steppers") were at that city's Paramount Theater. When they appeared at Spokane's Orpheum Theater (in a show that ran until March 11), the March 7 Spokane Press called them "dusky dancers from the south" (although they seem to have formed in California). The Chocs were, from the beginning, dancers. The Semi-Weekly Spokane Review of March 9 characterized them as follows:

The Three Chocolateers, ebon-hued tap dancers, work with the smoothness and precision of a machine with roller bearings and almost as ceaselessly. They switch from ensembles to solo work with no time out to catch the breath and leave the audience almost as breathless as they are. They are fast, furious and fancy. [A great review considering they were up against Bonzo, a "dog imitator". (No, I don't understand that either.)]

From there, they became part of a revue called "Harlem Rhapsody", which played in San Francisco in May 1934.

They must have impressed someone, because, in 1934, they made appearances in the Far East on a six-month contract. The Kansas City Call of August 24 had this: "Esvan Mosby, former Kansas Citian, sailed on the steamship Maru for Shanghai, China, with his act, the Three Chocolate Tears". (They were close.)

Esvan Mosby "brother of famous band leader" Curtis Mosby wrote back from Shanghai (he'd promised to keep people apprised of the group's adventures) and his letter was printed in the Chicago Defender (and probably other papers) on September 1, 1934. (The Chocolateers appeared with Buck Clayton's Orchestra at the Canidrome Ballroom in Shanghai.) Esvan never mentions the names of the other two (and, in fact, rarely refers to any others at all; almost all of the letter deals with "I"). Here's the relevant portion of what he wrote:

I am having the time of my life, the Japanese people are very nice. I don't know I am colored. I went to a dance on first class, danced with anyone - and did a number then a couple of nights later I put a show on and made a big hit. [sic for that whole sentence] There are some Hawaiians of the ship that play - had a nice show. I have the nicest little Japanese girl I have ever met. She is swell. I will send you a picture of her from Shanghai. Will give you as much dope as I can on everything over there.... We had a little trouble in San Francisco, after we left the ship, two blocks away we ran into some strikers, they asked us what ship were we from. We had our passes but I had to do them a dance to convince them that we wasn't [sic] scabs.

So who were the 3 Chocolateers at the beginning? Read on.

Fortunately, there's a record of them returning home from Kobe, Japan, sailing on December 25, 1934 and landing in Seattle on January 11, 1935. The manifest names them as Esvan Mosby (born April 21, 1910, in Kansas City, Missouri), our now-familiar "juvenile wonder", Albert Gibson (born June 12, 1913, in Atlanta, Georgia), and Guss [sic] Moore (born September 12, 1906, in Austin, Texas). All live in Los Angeles. Their passports were issued in July, which is probably when they first went. All three listed their occupation as "dancer". Since the ship first docked in Vancouver, British Columbia, they were required to list where they were going in the U.S. Moore gave his address; Mosby said he was going to his brother, George, in Los Angeles; and Gibson said he was going to his cousin, George Mosby, in Los Angeles. If true, this would make Esvan Mosby and Albert Gibson cousins, something that was never mentioned in any blurb about the group.

Right from the beginning there are problems with their names. Mosby is on the manifest as "Scott Esvan Mosby", but his name was actually Esvan Scott Mosby. Gibson, too, was confused about his own name. It almost always appears as "Gibson", but he, himself, spelled it "Gipson" on at least one autograph. Moore's name was actually Leo Augustus Moore, but he called himself "Guss" or "Gus". I did find mention of a Guss Moore who was in a revue called "Lucky Day" that opened in Los Angeles in December 1931, with music by Leon and Otis Rene; presumably this is him. Also, Guss Moore, a dancer, registered to vote in California in 1938. However, soon after the tour, Moore left the group, to be replaced by Paul Black.

On October 11, 1935, they opened at the Beacon Theater in Vancouver, British Columbia as part of a Vaudeville show. Their act was called "Hotcha From Harlem".

On December 20, 1935, they took out an ad in the California Eagle (a Los Angeles paper) to wish people season's greetings. They gave their names: Esvan Mosby, Albert Gibson, and Paul Black. At the time, they were at the Apex Nite Club (Los Angeles) and also, it said, working in Showboat. While this is a nice publicity touch, it wouldn't have been meaningful unless the 3 Chocolateers were somewhat known locally.

On December 20, 1935, they took out an ad in the California Eagle (a Los Angeles paper) to wish people season's greetings. They gave their names: Esvan Mosby, Albert Gibson, and Paul Black. At the time, they were at the Apex Nite Club (Los Angeles) and also, it said, working in Showboat. While this is a nice publicity touch, it wouldn't have been meaningful unless the 3 Chocolateers were somewhat known locally.

In February 1936, Paul Black was present when Esvan Mosby married Henrietta Cox. Albert Gibson wasn't mentioned, but it would have been strange if he weren't there too.

In March, 1936, they appeared at the Club Alabam, in Los Angeles, along with Lorenzo Flennoy's orchestra. The club was owned by Esvan's brother, Curtis Mosby (a former drummer and bandleader). July found them at the Apex Nite Club (also owned by Curtis), and, on August 21, they were part of "A Night Of Joy" at the Masonic Temple.

In March, 1936, they appeared at the Club Alabam, in Los Angeles, along with Lorenzo Flennoy's orchestra. The club was owned by Esvan's brother, Curtis Mosby (a former drummer and bandleader). July found them at the Apex Nite Club (also owned by Curtis), and, on August 21, they were part of "A Night Of Joy" at the Masonic Temple.

And then there was "Peckin'". The origins of the song are lost in time, since there are many competing versions of how it began. It was written by bandleader Ben Pollack and his new trumpet player, Harry James, sometime in 1936. One story has it that the 3 Chocolateers were appearing, along with Pollack's orchestra, at Frank Sebastian's Cotton Club, in Culver City, California, where they did a dance to the tune, imitating chickens. There were many dances that had "animal" names: the fox trot, the turkey trot, the camel walk (even Chubby Checker's "The Fly"). Pollack's unit recorded the tune (as an instrumental) on December 18, 1936, although it wasn't released until around May of the following year. (The basic tune to "Peckin'", however, seems to have been the Charles "Cootie" Williams' trumpet solo portion of Duke Ellington's 1931 "Rockin' In Rhythm".)

And then there was "Peckin'". The origins of the song are lost in time, since there are many competing versions of how it began. It was written by bandleader Ben Pollack and his new trumpet player, Harry James, sometime in 1936. One story has it that the 3 Chocolateers were appearing, along with Pollack's orchestra, at Frank Sebastian's Cotton Club, in Culver City, California, where they did a dance to the tune, imitating chickens. There were many dances that had "animal" names: the fox trot, the turkey trot, the camel walk (even Chubby Checker's "The Fly"). Pollack's unit recorded the tune (as an instrumental) on December 18, 1936, although it wasn't released until around May of the following year. (The basic tune to "Peckin'", however, seems to have been the Charles "Cootie" Williams' trumpet solo portion of Duke Ellington's 1931 "Rockin' In Rhythm".)

The 3 Chocolateers were selected to do some dancing in the 20th Century Fox movie "Can This Be Dixie", starring a 10-year-old Jane Withers and released in November 1936. They're dancing in the (incredibly insensitive) "Pick Pick Pickaninny" number, where they do a "Peckin'" routine. They also dance in the "Uncle Tom's Cabin Is A Cabaret Now" night club scene (sung by the 5 Jones Boys). The only reason I know about this is that it's mentioned in a 1942 article about them; they received no credit in the film.

The 3 Chocolateers were selected to do some dancing in the 20th Century Fox movie "Can This Be Dixie", starring a 10-year-old Jane Withers and released in November 1936. They're dancing in the (incredibly insensitive) "Pick Pick Pickaninny" number, where they do a "Peckin'" routine. They also dance in the "Uncle Tom's Cabin Is A Cabaret Now" night club scene (sung by the 5 Jones Boys). The only reason I know about this is that it's mentioned in a 1942 article about them; they received no credit in the film.

In February, 1937, they were at the Culver City Cotton Club (or were still there from the prior year). The dance, simple and dumb as it was, took off quickly. On March 3, Cab Calloway recorded the song (in, what is to me, an unusually uninspired performance for him).

Another February event was Albert getting arrested for marijuana possession, a felony in California. He had just left the Cotton Club and was pulled over for driving recklessly and failing to heed a stop sign. When he was searched, the police found a number of marijuana cigarettes on him. Papers are good at reporting things like this; they're really bad at following up on them. Since Albert received no jail time, I assume that the charges were dismissed.

By March, famed (even back then) comic Pigmeat Markham was doing the "Peckin'" dance at New York's Cotton Club. It was opined that it would drive out "Truckin'". In a May 15 article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the tune was credited to trumpeter "Harry Jones" (and, they gave directions for the dance that even a chicken couldn't follow).

I'm not sure if it was because of the dance (probably not), but they became part of the general black chorus in the Marx Brothers "A Day At The Races" (MGM), in a scene that also has Ivie Anderson and the Dandridge Sisters. The chorus sings and dances to "All God's Chillun"/"Who Dat Man", but I can't pick out the Three Chocolateers, who are just "Black Performers" (uncredited); they have no solo number. The film was released June 11, 1937, at the same time that they were appearing at the Club Alabam, once again with Lorenzo Flennoy's orchestra. After that, they appeared, along with Duke Ellington and Ivie Anderson, at the Stanley Theater in Pittsburgh.

Benny Goodman got around to recording "Peckin'" (as an instrumental) on July 6, 1937. This tells you something: it was big if Goodman recorded it. It was also recorded on May 20 by the Johnny Hodges Orchestra (some of Ellington's musicians) with Cootie Williams not only reprising his 1931 trumpet performance, but also doing the vocal. There were other versions, notably Jimmy Dorsey's (with a vocal by Bing Crosby!), released in June.

Benny Goodman got around to recording "Peckin'" (as an instrumental) on July 6, 1937. This tells you something: it was big if Goodman recorded it. It was also recorded on May 20 by the Johnny Hodges Orchestra (some of Ellington's musicians) with Cootie Williams not only reprising his 1931 trumpet performance, but also doing the vocal. There were other versions, notably Jimmy Dorsey's (with a vocal by Bing Crosby!), released in June.

But now, success. Sometime in early 1937, they were invited to be part of the movie "New Faces Of 1937" (RKO), with Joe Penner, Harriet Hilliard, and Milton Berle. This was the vehicle (released on July 1) that introduced "Peckin'" to the general public (and kept the Chocs working for many a year). They start in a barnyard, imitating the chickens (and singing to a bewildered-looking trained Minorca rooster), move into a kitchen, and become waiters in a black nightclub. A maid introduces the move (it really can't be called a dance) to Harriet Hilliard (of future "Ozzie And Harriet" fame) as the "bride", who then has a "Peckin' Wedding". The 3 Chocolateers were named in the press: Paul Black, Albert Gibson, and Esvan Mosby. The August 19, 1937 Auburn (California) Journal had a big article on what it took to film the sequence.

But now, success. Sometime in early 1937, they were invited to be part of the movie "New Faces Of 1937" (RKO), with Joe Penner, Harriet Hilliard, and Milton Berle. This was the vehicle (released on July 1) that introduced "Peckin'" to the general public (and kept the Chocs working for many a year). They start in a barnyard, imitating the chickens (and singing to a bewildered-looking trained Minorca rooster), move into a kitchen, and become waiters in a black nightclub. A maid introduces the move (it really can't be called a dance) to Harriet Hilliard (of future "Ozzie And Harriet" fame) as the "bride", who then has a "Peckin' Wedding". The 3 Chocolateers were named in the press: Paul Black, Albert Gibson, and Esvan Mosby. The August 19, 1937 Auburn (California) Journal had a big article on what it took to film the sequence.

A revolving stage, taking the audience through a series of scenes describing the origin of a dance, its development and final popular acclaim, is employed for the grand finale of "New Faces of 1937", which plays at the State Theatre Sunday, [and] Monday, August 22 and 23.

Not uncommon to the stage, revolving sets are seldom used in motion pictures because of the wider scope of the camera.

However, "New Faces of 1937" being a "show within a show", and a greater part of its action taking place on a theatre stage, RKO Radio gives cinema audiences the same effect theoretically enjoyed by a theatre audience.

In filming what promises to be the newest dance sensation, "Peckin'", dance director Sammy Lee began his action in a barnyard setting. Cooing doves perch on their cote, two pigs root at a trough, ducks waddle in a pond and chickens peck about the yard. A four-year-old trained Minorca rooster stands patiently in center stage and remains immobile while The Three Chocolateers - Paul Black, Albert Gibson and Esvan Mosby - do their original eccentric dance, "Peckin'."

As the dance progresses, the stage revolves and the three colored boys pass through a door to enter an elaborate kitchen. As they don waiters' jackets, their "Peckin'" motion is picked up by the cooks. Picking up their chicken filled trays, they move into a night club setting as the stage again revolves. In one corner is a colored band playing the tune "Peckin'." Seated about black cellophane covered tables are Negro folk. Flanked by ramps leading to the dance floor is a huge Genii.

Not since RKO Radio designers confronted the task of creating "King Kong" did they have a similar problem in construction. The principal decorative feature of the cafe, the Genii, weighs three tons, and stands 25 feet high and 18 feet wide. Three horns, six feet long, give his head a devil-like appearance. His eyes, two arc lights, work as spotlights for the entertainers. Five men were employed inside the Genii's head to operate the eye lights and steam pipes, which emit smoke from the monster's nose.

As the Chocolateers enter, every guest picks up the head pecking movement. Their dance is augmented by a colored chorus of thirty girls, dressed in black sequin tights with yellow plumage cocked from their backs and headdress. [An interesting guess because the film was in black and white.]

As the dancers finish, the stage again revolves to reveal a lavish boudoir where Harriet Hilliard prepares for her wedding. A "peckin'" maid enters, and as she helps her mistress dress, Miss Hilliard adopts the movement.

Passing along to a hallway as the stage again revolves, Miss Hilliard meets her bridesmaids, each carrying an ostrich feather bouquet. They assimilate the peckin' movement as the entire group slowly marches to the living room where the wedding is held.

The revolving stage discloses the last setting, a satin draped room with an ostrich feather altar and plumes decorating the backgrounds. RKO Radio used more than 1000 yards of satin and georgette to decorate this setting. From a Northern California ostrich farm, more than 1500 ostrich plumes were purchased for the decorations and feathered bouquets.

As the bridal procession enters, every one picks up the peckin' movement, even the minister, Arthur "Skeets" Herfort, who conducts the ceremony.

Miss Hilliard and William Brady, romantic leading man of the picture, are wedded to the strains of "Peckin'", the dance describing music, introduced in the RKO musical comedy revue picture.

Not everyone loved the number. Gould Cassal, the film reviewer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle said (July 2, 1937): "In this [the "Peckin'" number] the whole cast shake themselves into a finale. By that time, this reporter had prayed in vain for an epidemic of rigor mortis."

In early August 1937, they were with Duke Ellington at Chicago's Palace Theater. On August 27, they made their first appearance at New York's Apollo Theater, sharing the bill with Blanche Calloway. Possibly this is what led to a years-long association with her brother, bandleader Cab Calloway.

In early August 1937, they were with Duke Ellington at Chicago's Palace Theater. On August 27, they made their first appearance at New York's Apollo Theater, sharing the bill with Blanche Calloway. Possibly this is what led to a years-long association with her brother, bandleader Cab Calloway.

On September 24, 1937, they became part of the Cab Calloway "Cotton Club Parade" fall revue at New York's Cotton Club. By this time, the Cotton Club, probably the finest of the whites-only nightclubs in Harlem, had moved downtown to Broadway and 48th Street. This followed the 1935 riots that, it was felt, left Harlem unsafe for white audiences. The shows put on at the Cotton Club were not the same as, for example, those put on at the Apollo Theater. In most venues, an act was there for a week or two, not interacting at all with the other acts. On the other hand, Cotton Club shows, which lasted for months, were lavish affairs with musical scores, costumes, and scenery created expressly for them. (For example, Julian Harrison, who was once the scenic designer for Cecil B. DeMille, redecorated the club for Calloway's revue.)

On September 24, 1937, they became part of the Cab Calloway "Cotton Club Parade" fall revue at New York's Cotton Club. By this time, the Cotton Club, probably the finest of the whites-only nightclubs in Harlem, had moved downtown to Broadway and 48th Street. This followed the 1935 riots that, it was felt, left Harlem unsafe for white audiences. The shows put on at the Cotton Club were not the same as, for example, those put on at the Apollo Theater. In most venues, an act was there for a week or two, not interacting at all with the other acts. On the other hand, Cotton Club shows, which lasted for months, were lavish affairs with musical scores, costumes, and scenery created expressly for them. (For example, Julian Harrison, who was once the scenic designer for Cecil B. DeMille, redecorated the club for Calloway's revue.)

The Chocs joined a cast of over 150 that included the Nicholas Brothers. (They were brought in to temporarily replace Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who had a sudden Hollywood commitment for a Shirley Temple film. The show's opening was delayed a week, so that young Harold Nicholas, only 16 at the time, could learn all of Bojangles' routines. On November 30, when Robinson was finally free to join the show, the Nicholas Brothers left. Robinson subsequently said: "It's just a switch from the little Heidi to the big Hi-De-Ho.") Other cast members were Avis Andrews; Mae Johnson; Tip, Tap & Toe; Will Vodery's Jubileers; the Six Cotton Club Boys; James Skelton; the Lindy Hoppers; Dynamite Hooker; the Tramp Band (something like a black Spike Jones aggregation); and 50 showgirls. Both Calloway's orchestra and Arthur Davy's band played for dancing between shows. In its first week, the revue shattered all previous records for the club (15,000 patrons had plunked down their money). There were three shows a night, the last starting at 2:30 AM. New songs for the revue included "Tall, Tan And Terrific" (the way the chorus girls were billed), "Harlem Bolero" (danced and sung by the entire cast), "I'm Always In The Mood For You", and (when Bojangles finally joined) "the "Bill Robinson Walk". One stand-out number was Calloway's "Hi-De-Ho Romeo", sung with Mae Johnson as Juliet. The Calloway revue lasted until early February 1938, when Calloway took it on the road.

The Chocs joined a cast of over 150 that included the Nicholas Brothers. (They were brought in to temporarily replace Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, who had a sudden Hollywood commitment for a Shirley Temple film. The show's opening was delayed a week, so that young Harold Nicholas, only 16 at the time, could learn all of Bojangles' routines. On November 30, when Robinson was finally free to join the show, the Nicholas Brothers left. Robinson subsequently said: "It's just a switch from the little Heidi to the big Hi-De-Ho.") Other cast members were Avis Andrews; Mae Johnson; Tip, Tap & Toe; Will Vodery's Jubileers; the Six Cotton Club Boys; James Skelton; the Lindy Hoppers; Dynamite Hooker; the Tramp Band (something like a black Spike Jones aggregation); and 50 showgirls. Both Calloway's orchestra and Arthur Davy's band played for dancing between shows. In its first week, the revue shattered all previous records for the club (15,000 patrons had plunked down their money). There were three shows a night, the last starting at 2:30 AM. New songs for the revue included "Tall, Tan And Terrific" (the way the chorus girls were billed), "Harlem Bolero" (danced and sung by the entire cast), "I'm Always In The Mood For You", and (when Bojangles finally joined) "the "Bill Robinson Walk". One stand-out number was Calloway's "Hi-De-Ho Romeo", sung with Mae Johnson as Juliet. The Calloway revue lasted until early February 1938, when Calloway took it on the road.

In November 1937, the Chocs played a three-week engagement at New York's Paramount Theater, along with the Tommy Dorsey orchestra. Archer Winston's November 4, review column in the New York Post liked the stage show better than Marlene Dietrich in "Angel". He said: "The Three Chocolateers, originators of that remarkably silly dance, "Peckin'", do it so fantastically that they justify their own invention." Since they were concurrently appearing at the Cotton Club, this must have been exhausting. The Paramount was at 43rd and Broadway, so it's probable that the Chocs just ran the five blocks between performances. (Cab Calloway had it a little easier. He did his 11:00 PM nightly radio show direct from the Cotton Club.)

A February 19, 1938 review (in the Pittsburgh Courier) said: "Naw, you have never seen supreme "Peckin'" unless you have seen the Chocolateers do it. In their "Peckin'" number those guys keep the house in an uproar with laughter and applause from the beginning to the end. They knocked me out cold, I tell ya." However, another reviewer complained that the show was too heavy on dancing.

But nothing lasts forever. The new dance is the "Skrontch", a song written by Duke Ellington and recorded by Cab Calloway on January 23, 1938. His version was somewhat boring, unlike the cover by Fats Waller. (That's the second time I've minimized a Calloway performance. I feel bad about this, because he's one of my favorite entertainers.) Of course, the Chocs created a dance routine for it, which they performed during their ensuing Cotton Club engagement.

On March 10, 1938, the spring 1938 Cotton Club Parade revue opened. This one featured Duke Ellington, with a score he'd written himself. Songs included "'Tis Autumn", "Don't Take Your Love From Me", "If You Were In My Place", and "I Let A Song Go Out Of My Heart" (all with lyrics by Henry Nemo). This show would be a full two hours long. There were a few holdovers from the prior cast: the 3 Chocolateers, Mae Johnson (who continued "Hi-De-Ho Romeo" as a solo), and Will Vodery's Jubileers. Also on the bill were the Peters Sisters (each touted at over 300 pounds), Peg Leg Bates, Aida Ward, the 4 Step Brothers, Rufus & Richard (ages 7 and 5), and Anise & Aland. One big production number was Ellington's "Skrontch". It was reviewed by Hy Gardner as follows: "As modeled by the Chocolateers, three hilarious, unkempt, lowdown and regaling ragimuffins [sic] who steal the show, this new dance is so breathtaking it leaves you 'Skrunch-Drunk' [cute]." Gardner went on to say that, good as this show was, the prior Calloway revue was better. The show ran until May 31.

On March 10, 1938, the spring 1938 Cotton Club Parade revue opened. This one featured Duke Ellington, with a score he'd written himself. Songs included "'Tis Autumn", "Don't Take Your Love From Me", "If You Were In My Place", and "I Let A Song Go Out Of My Heart" (all with lyrics by Henry Nemo). This show would be a full two hours long. There were a few holdovers from the prior cast: the 3 Chocolateers, Mae Johnson (who continued "Hi-De-Ho Romeo" as a solo), and Will Vodery's Jubileers. Also on the bill were the Peters Sisters (each touted at over 300 pounds), Peg Leg Bates, Aida Ward, the 4 Step Brothers, Rufus & Richard (ages 7 and 5), and Anise & Aland. One big production number was Ellington's "Skrontch". It was reviewed by Hy Gardner as follows: "As modeled by the Chocolateers, three hilarious, unkempt, lowdown and regaling ragimuffins [sic] who steal the show, this new dance is so breathtaking it leaves you 'Skrunch-Drunk' [cute]." Gardner went on to say that, good as this show was, the prior Calloway revue was better. The show ran until May 31.

On March 12, the Porter Roberts column in the Pittsburgh Courier printed a letter from a Flink Moore saying that he was the originator of "Peckin'". He credits the music to Ben Pollack, but claims that the words and dance were his and that he taught them to the Chocolateers. While I doubt that anyone believed Flink (a dancer and comedian, once part of "Flink And Dink", an act that morphed into "Dink, Blink, and Dink"), is it possible that this is the long-lost Guss Moore, original member of the 3 Chocolateers? The answer is "no", since "Flink" wasn't a nickname; his actual name was Flink Carl Moore.

On March 12, the Porter Roberts column in the Pittsburgh Courier printed a letter from a Flink Moore saying that he was the originator of "Peckin'". He credits the music to Ben Pollack, but claims that the words and dance were his and that he taught them to the Chocolateers. While I doubt that anyone believed Flink (a dancer and comedian, once part of "Flink And Dink", an act that morphed into "Dink, Blink, and Dink"), is it possible that this is the long-lost Guss Moore, original member of the 3 Chocolateers? The answer is "no", since "Flink" wasn't a nickname; his actual name was Flink Carl Moore.

Another routine that they used at the Cotton Club was the "Penguin Swing", a song that would eventually be recorded by Cab Calloway in October 1938. One reviewer opined that it would be "Penguin Swing" and not "Skrontch" that would be the next big hit. Actually, "Penguin Swing" was pretty much an instrumental version of Cab's earlier "Peck-A-Doodle-Do".

In June, they appeared at the Surfside, in Long Beach, NY. They shared the bill with the Don Redman orchestra and Aida Ward. After that, it was back to Manhattan's Cotton Club. On August 5, 1938 they had another appearance at the Apollo, along with Slim & Slam and the Savoy Sultans. From there, it was off to the Regal, in Chicago, and then the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.

In June, they appeared at the Surfside, in Long Beach, NY. They shared the bill with the Don Redman orchestra and Aida Ward. After that, it was back to Manhattan's Cotton Club. On August 5, 1938 they had another appearance at the Apollo, along with Slim & Slam and the Savoy Sultans. From there, it was off to the Regal, in Chicago, and then the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.

On November 18, they appeared (probably for a week), with Lucky Millinder's band, at the Brooklyn Strand. They (the "Cotton Club "Peckin'" Champs") were matched against Joe & Jane McKenna ("Famous dancing sensations"). I suppose that was some sort of dance "contest".

On November 18, they appeared (probably for a week), with Lucky Millinder's band, at the Brooklyn Strand. They (the "Cotton Club "Peckin'" Champs") were matched against Joe & Jane McKenna ("Famous dancing sensations"). I suppose that was some sort of dance "contest".

January 1939 found them at Washington, D.C.'s Howard Theater, along with Don Redman's orchestra (and dance numbers by the Twelve Peckin' Peaches). In February, they appeared, along with Peg Leg Bates, at Broadway's Roxy Theater. In late April, it was Baltimore's Royal Theater.

There's no further mention of them until they were back in New York for Clarence Robinson's revue at the Apollo on August 18, 1939. They shared the stage with the Ernie Fields Orchestra, and Princess Orelia & Her African Troupe. It was then announced that they'd be going back to California to appear at the State Fair. On their return to New York, they stopped off in Chicago (but the blurb didn't say where they appeared).

September 28 found them at the Flatbush Vaudeville Theater, along with Cab Calloway's orchestra (with Chu Berry and Cozy Cole), Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and the Cab Jivers. In November, they appeared (with Calloway) at the Circle Theater in Indianapolis. The Indianapolis Star of November 4 said: "The Three Chocolateers offer eccentric tap routines in the best Harlem manner...." They were also with him in January 1940, when he played the Orpheum Theater in Memphis.

September 28 found them at the Flatbush Vaudeville Theater, along with Cab Calloway's orchestra (with Chu Berry and Cozy Cole), Sister Rosetta Tharpe, and the Cab Jivers. In November, they appeared (with Calloway) at the Circle Theater in Indianapolis. The Indianapolis Star of November 4 said: "The Three Chocolateers offer eccentric tap routines in the best Harlem manner...." They were also with him in January 1940, when he played the Orpheum Theater in Memphis.

The next mention of the Chocs is in June 1940, when they were still touring with Cab Calloway's Cotton Club Revue, which included the Six Cotton Club Boys, the Cab Jivers, and Avis Andrews. One stop was the Paramount Theater on Broadway; others were the Fox in Detroit and the Palace in Akron.

The next mention of the Chocs is in June 1940, when they were still touring with Cab Calloway's Cotton Club Revue, which included the Six Cotton Club Boys, the Cab Jivers, and Avis Andrews. One stop was the Paramount Theater on Broadway; others were the Fox in Detroit and the Palace in Akron.

In late August, they were part of a show at Jones Beach, New York. It "depicts a Plantation Night with all the charm of the old south", said the August 24 Brooklyn Citizen.

The September 14, 1940 Chicago Defender talks about the new song "The Hicky Ricky". It was written by Albert Gibson, Esvan Mosby, and arranger/former bandleader Chappie Willet. Paul Black got some credit for the lyrics on the 1940 copyright, but not in subsequent filings. (In an autographed photo, Esvan spelled it "Hickey Rickey".) In early September, when they were with Cab Calloway at the Circle Theater in Indianapolis, the Indianapolis News of September 7 said: "... a trio of dancers who, while they are on the stage, apparently forget there is such a word as repose, These three men dance, skip, slide, jump and perform all sorts of feats at an inhumanly rapid pace. They also introduce a new dance titled Ricky-Hicky [sic]." From there, the show went to the Rialto in Louisville.

The September 14, 1940 Chicago Defender talks about the new song "The Hicky Ricky". It was written by Albert Gibson, Esvan Mosby, and arranger/former bandleader Chappie Willet. Paul Black got some credit for the lyrics on the 1940 copyright, but not in subsequent filings. (In an autographed photo, Esvan spelled it "Hickey Rickey".) In early September, when they were with Cab Calloway at the Circle Theater in Indianapolis, the Indianapolis News of September 7 said: "... a trio of dancers who, while they are on the stage, apparently forget there is such a word as repose, These three men dance, skip, slide, jump and perform all sorts of feats at an inhumanly rapid pace. They also introduce a new dance titled Ricky-Hicky [sic]." From there, the show went to the Rialto in Louisville.

Albert Gibson's World War 2 Draft Registration (on October 16, 1940) says he's "unemployed now - expects engagement with Cab Calloway".

On November 20, they had an odd gig: the fourth annual Thanksgiving Ball of the Congregation Ahavath Israel (at the Municipal Auditorium, Kingston, New York). Can't say I ever heard of anyone on the bill, other than Morey Amsterdam, who acted as Master Of Ceremonies.

Friday, February 14, 1941 saw the Chocs beginning a week at the Apollo Theater, along with Les Hite's Orchestra. Of course, they did their "Hicky Ricky" routine. From there, they went to the Sea Girt Inn, in Sea Girt, New Jersey.

Friday, February 14, 1941 saw the Chocs beginning a week at the Apollo Theater, along with Les Hite's Orchestra. Of course, they did their "Hicky Ricky" routine. From there, they went to the Sea Girt Inn, in Sea Girt, New Jersey.

In early 1941, Paul Black left to join up with Slim & Eddie (Melvin Marvin and Eddie West) for a new act (unimaginatively called "Paul, Slim & Eddie"). By November, Paul and his new group were appearing with Cab Calloway at the Apollo.) Paul's replacement in the Chocs was Bethel "Duke" Gibson, Jr., Albert's younger brother (born in 1921).

In early 1941, Paul Black left to join up with Slim & Eddie (Melvin Marvin and Eddie West) for a new act (unimaginatively called "Paul, Slim & Eddie"). By November, Paul and his new group were appearing with Cab Calloway at the Apollo.) Paul's replacement in the Chocs was Bethel "Duke" Gibson, Jr., Albert's younger brother (born in 1921).

A big headline in the April 5, 1941 Chicago Defender announced "Chocolateers' Tune Used In Navy Film". It went on to describe how the "Hicky Ricky" (or "Hickory Rickory" as the article had it) was going to be sung by the Andrews Sisters in the Abbot and Costello film "We're In The Navy Now" (subsequently retitled "In The Navy"). The Chocs were to be paid $5000 for the use of the song and its accompanying dance. The only problem? The routine, if actually filmed at all, was cut from the final movie. I hope they complained when they were in Los Angeles in November to appear at the Paramount Theater. (Although, now that I think about it, I'd be happy to accept $5000 from anyone who doesn't want to use one of my articles.)

In mid-June, they were at the Rhum Boogie Club in Los Angeles. The members were named as Esvan Mosby, Albert Gibson, and Bethel Gibson. Bethel (Junior) is always referred to, except in this one blurb, as "Duke"

In August, they were back in California, playing three weeks at the Golden Gate (San Francisco) and setting a record there for box office receipts. The August 30 Phoenix Index called them "famed exponents of tapprecision". After that, they were off to Los Angeles, then to Dallas, for the Texas State Fair.

October 1941 found them at the Club Del Rio in San Pedro, California. They were billed as being "direct from Duke Ellington's 'Jump For Joy'" revue. In November, they appeared at Fort Haan, in Riverside, California. Esvan Mosby (named as both member and manager) was recovering from an accident that had occurred during their act in a nightclub. Also in November, they were at the Trianon, in South Gate (a Los Angeles suburb), with Bob Crosby's orchestra. They were still there in January 1942.

October 1941 found them at the Club Del Rio in San Pedro, California. They were billed as being "direct from Duke Ellington's 'Jump For Joy'" revue. In November, they appeared at Fort Haan, in Riverside, California. Esvan Mosby (named as both member and manager) was recovering from an accident that had occurred during their act in a nightclub. Also in November, they were at the Trianon, in South Gate (a Los Angeles suburb), with Bob Crosby's orchestra. They were still there in January 1942.

Then it was on to the Club Alabam (Los Angeles) in February. It was reported that Esvan had been sick and the two Gibson Brothers had to work alone. In March, the Chocs, Hattie McDaniel, and Mantan Moreland appeared in San Bernadino, California, to do a show for servicemen.

The 3 Chocolateers did one more film, "Moonlight Masquerade" (Republic Pictures), with Dennis O'Keefe and Jane Frazee. Esvan Mosby, Albert Gibson, and Duke Gibson appear as railroad porters and perform a dance number as a "specialty" act; however, most of it was cut from the final print. While one of them (I think it's Albert) gets some screen time, the group is only on the screen for less than five seconds (Esvan and Duke magically appearing out of thin air). One source ("Annual Review Of Jazz Studies 14") claimed that they sang "Hicky Ricky" in the film. If so, it was cut with most of their dance routine. The film was released on June 10, 1942. Strangely, since they were barely in the final film, their name was associated with it in ads and write-ups through the end of the year.

The 3 Chocolateers did one more film, "Moonlight Masquerade" (Republic Pictures), with Dennis O'Keefe and Jane Frazee. Esvan Mosby, Albert Gibson, and Duke Gibson appear as railroad porters and perform a dance number as a "specialty" act; however, most of it was cut from the final print. While one of them (I think it's Albert) gets some screen time, the group is only on the screen for less than five seconds (Esvan and Duke magically appearing out of thin air). One source ("Annual Review Of Jazz Studies 14") claimed that they sang "Hicky Ricky" in the film. If so, it was cut with most of their dance routine. The film was released on June 10, 1942. Strangely, since they were barely in the final film, their name was associated with it in ads and write-ups through the end of the year.

The lyrics to "Hicky Ricky" mention Peckin', the Susie-Q, the Conga, and the Skrontch. The song was supposed to be recorded by Harry James, the Andrews Sisters, and Duke Ellington, but probably wasn't. [Note that there exists a version of the song credited to "Stanford Mosby" (although whoever is announcing him clearly says "Esvan Mosby" at the end of the rendition). It's an unimpressive, crudely-done a cappella version from the late 40s or early 50s (datable because Esvan is referred to as "Central Avenue's Mayor", something he'd start being called around 1948).]

The guys then made a couple of Soundies (actually, they were filmed by RCM and distributed by Soundies). The pre-recordings of "Peckin'" and "Harlem Rhumba" were done on September 26; The music track to "Tweed Me" had been recorded by the John Kirby Sextet on July 30 in Chicago. Filming to these soundtracks was done on October 7. While Lenny Bluett played piano on the recordings, when it came time to film, RCM used Eugene "Pineapple" Jackson. Thanks to Mark Cantor (Celluloid Improvisations Music Film Archive) for this information. Since Duke Gibson went into the Army on September 25, I'm not sure how he convinced them to let him film these.

The guys then made a couple of Soundies (actually, they were filmed by RCM and distributed by Soundies). The pre-recordings of "Peckin'" and "Harlem Rhumba" were done on September 26; The music track to "Tweed Me" had been recorded by the John Kirby Sextet on July 30 in Chicago. Filming to these soundtracks was done on October 7. While Lenny Bluett played piano on the recordings, when it came time to film, RCM used Eugene "Pineapple" Jackson. Thanks to Mark Cantor (Celluloid Improvisations Music Film Archive) for this information. Since Duke Gibson went into the Army on September 25, I'm not sure how he convinced them to let him film these.

The first of these, released November 9, was the evergreen "Peckin'". This, without Hollywood interference, is probably close to what their stage act looked like (it's just them, accompanied by only a pianist). I don't know if it originated with them (probably not), but they're doing the "duck walk" copied by Chuck Berry in the 50s. "Harlem Rhumba" was released on December 21 and "Tweed Me" on December 31.

But things were about to change. As I said, Duke Gibson went into the Army and Esvan Mosby left for unknown reasons (by late 1942 he was doing war work at North American Aircraft). Albert Gibson must have felt lonely at this point. However, Paul Black returned, bringing Eddie West (his partner from "Paul, Slim & Eddie"). It wasn't immediate, however. Duke went into the Army in late September 1942 and "Paul, Dinky, and Eddy" were still performing, in Detroit, in late March 1943. I don't know what was going on in between.

The May 1, 1943 New York Age reported that Una Mae Carlisle and the Three Chocolateers were appearing at the Plantation Club on New York's 52nd Street. No names were given. In July, they were at the Mandarin Supper Club in Vancouver, British Columbia.

And then, in a September 22, 1943 blurb, Albert Gibson was characterized as "ex of the Chocolateers" (turns out he'd been drafted). I don't know who the new third member was; possibly Esvan was persuaded to return. In late June-early July 1943 they turned up at the Mandarin Supper Club in Vancouver, British Columbia.

And then, in a September 22, 1943 blurb, Albert Gibson was characterized as "ex of the Chocolateers" (turns out he'd been drafted). I don't know who the new third member was; possibly Esvan was persuaded to return. In late June-early July 1943 they turned up at the Mandarin Supper Club in Vancouver, British Columbia.

By October 1943, they were part of Cab Calloway's "Jumpin' Jive Jubilee" revue. When it played the Stanley Theater (Pittsburgh) the reviewer wasn't kind, saying "the show staggers all over the place" and the 3 Chocolateers "have only their energy to recommend them." However, another reviewer, in November, said "Of the troupe of artists that the jive linguist [Calloway, who was known for his jive talk] carries with him, the Three Chocolateers are head and shoulders above the rest of the vaudevillers. Featuring a fast dancing routine, the boys slip into a pantomime based around the microphone and wind it up with a free-for-all slapstick at the expense of the number three man in the act dressed as a passe Harlem belle."

By October 1943, they were part of Cab Calloway's "Jumpin' Jive Jubilee" revue. When it played the Stanley Theater (Pittsburgh) the reviewer wasn't kind, saying "the show staggers all over the place" and the 3 Chocolateers "have only their energy to recommend them." However, another reviewer, in November, said "Of the troupe of artists that the jive linguist [Calloway, who was known for his jive talk] carries with him, the Three Chocolateers are head and shoulders above the rest of the vaudevillers. Featuring a fast dancing routine, the boys slip into a pantomime based around the microphone and wind it up with a free-for-all slapstick at the expense of the number three man in the act dressed as a passe Harlem belle."

On January 21, 1944, they were at the Apollo Theater again, this time with the Don Redman Orchestra, Dolores Brown, the Cabin Kids (a female trio), and femme singer Edna "Yack" Taylor. They had just finished an engagement at the Gayety Theater in Montreal.

On January 21, 1944, they were at the Apollo Theater again, this time with the Don Redman Orchestra, Dolores Brown, the Cabin Kids (a female trio), and femme singer Edna "Yack" Taylor. They had just finished an engagement at the Gayety Theater in Montreal.

After that, it was back to touring with Cab Calloway. In February, there was the Orpheum, in Los Angeles, then the Golden Gate, in San Francisco. In April (St. Louis), they were called "side-splitting". On May 5, the whole revue roared into the Apollo Theater. From there, it was on to the RKO-Boston Theater and back to New York to appear at the Strand on Broadway for a week (the show ended up being held over for three additional weeks).

After that, it was back to touring with Cab Calloway. In February, there was the Orpheum, in Los Angeles, then the Golden Gate, in San Francisco. In April (St. Louis), they were called "side-splitting". On May 5, the whole revue roared into the Apollo Theater. From there, it was on to the RKO-Boston Theater and back to New York to appear at the Strand on Broadway for a week (the show ended up being held over for three additional weeks).

On September 5, the Calloway tour over, they were at the Civic Theater in Portland, Maine. Then, on the 14, it was Loew's State Theater in New York. The reviewer loved them, saying that that the "outfit keeps up the killing pace until walkoff." (But for real entertainment, they shared the stage with Sharkey The Seal.) In his September 18 column, Ed Sullivan recommends seeing the 3 Chocolateers, without bothering to mention where they were appearing.

On September 5, the Calloway tour over, they were at the Civic Theater in Portland, Maine. Then, on the 14, it was Loew's State Theater in New York. The reviewer loved them, saying that that the "outfit keeps up the killing pace until walkoff." (But for real entertainment, they shared the stage with Sharkey The Seal.) In his September 18 column, Ed Sullivan recommends seeing the 3 Chocolateers, without bothering to mention where they were appearing.

They were back at the Apollo the week of September 29, along with Andy Kirk. It said they'd been reorganized (and that they were from Cleveland!). If there were any new members, they weren't named anywhere.

On May 21, 1945, they were part of a new show at the Belasco Theater (Manhattan) called "Blue Holiday". It starred Ethel Waters, Josh White, Willie Bryant, the Katherine Dunham Dancers, the Hall Johnson Choir, and Timmie Rogers. Some of the songs had been written by Morey Amsterdam, others by E.Y. Harburg. Reviewers didn't like either Timmie Rogers or the Chocs, saying that neither fit in. It closed five days later. In June, the Chocs returned to the Gayety Theater in Montreal. In August, they played the Club Harlem in Atlantic City.

They were at the Apollo again the week of November 30, 1945. This time, they shared the stage with Private Cecil Gant and the orchestra of Johnny "Scat" Davis.

February 1946 found them at the Shangri-La, in Philadelphia. From there, it was off to the State Theater in Hartford, Connecticut with the Mills Brothers; they got plenty of applause. In late March, they opened at the Cafe Baron in Harlem, with Ivie Anderson, as part of a Larry Steele revue. I would imagine that, by this time, Albert Gibson had re-joined the group.

In May, it was announced that Louis Armstrong was signing up acts for his new "Musical Revusical". The comedy-dancing duo of Slim & Sweets had already been signed, as well as the 3 Chocolateers. It opened at the Adams Theater, in Newark, but it couldn't have run very long, since he was at the Apollo Theater the week of June 7. On June 13, they were at Atlantic City's Club Harlem, along with Moms Mabley and Ada Brown, for the club's season opening. Called the "1946 Sepia Review", it ran the entire summer, until October 5.

In May, it was announced that Louis Armstrong was signing up acts for his new "Musical Revusical". The comedy-dancing duo of Slim & Sweets had already been signed, as well as the 3 Chocolateers. It opened at the Adams Theater, in Newark, but it couldn't have run very long, since he was at the Apollo Theater the week of June 7. On June 13, they were at Atlantic City's Club Harlem, along with Moms Mabley and Ada Brown, for the club's season opening. Called the "1946 Sepia Review", it ran the entire summer, until October 5.

Remember that Duke Gibson had enlisted in 1942? He was discharged on February 6, 1946. On July 19, 1946 he appeared at the Apollo with his new partner, Kenneth Mitchell (as "Mitchell & Gibson").

Remember that Duke Gibson had enlisted in 1942? He was discharged on February 6, 1946. On July 19, 1946 he appeared at the Apollo with his new partner, Kenneth Mitchell (as "Mitchell & Gibson").

On November 1, 1946 the Chocs opened at the Strand (on Broadway) with Lionel Hampton (who had Wini Brown and Madeline Greene). The reviewer basically liked their act, but not their "zoot-suited Harlem hipster routine".

January 31, 1947 found them doing a week at Detroit's Paradise Theater.

I don't know exactly when Esvan left the group (if he had ever come back at all after leaving in the summer of 1942), but by November 1946, he was Maitre d' at the New Club Alabam. An October 1947 article said that he'd been manager of L.A.'s Last Word Club (at least since January of that year) and was now becoming the manager of the Down Beat Club (at 4201 South Central Avenue). By 1948, he was referred to as "Mayor Of Central Avenue".

I don't know exactly when Esvan left the group (if he had ever come back at all after leaving in the summer of 1942), but by November 1946, he was Maitre d' at the New Club Alabam. An October 1947 article said that he'd been manager of L.A.'s Last Word Club (at least since January of that year) and was now becoming the manager of the Down Beat Club (at 4201 South Central Avenue). By 1948, he was referred to as "Mayor Of Central Avenue".

On September 12, 1947, the Chocs spent two weeks at the Latin Quarter in Cincinnati. Also on the bill was June Richmond. They were described as "long on slapstick and rapid-fire dancing" in the September 14 Cincinnati Enquirer.

The only other 1947 bookings I can find for the guys are in December. They started the month at the Riverside Theater (Milwaukee) with Lionel Hampton, Wini Brown, and Red & Curley. The Chocs were described as a "three ring dancing circus". The end of the month found them at the Loew's State (New York). They started on December 24, and a reviewer said "The Three Chocolateers with slapstick and terps [dancing], put in a fast few minutes and bring yocks aplenty.""

On January 20, 1948, they played the Tri-Boro Theater (Astoria, Queens); the 22nd saw them at the Bedford (Brooklyn). On February 12, it was the Ebony Club (Broadway), along with 225 pound June Richmond and Billy Daniels. February 20 found them at the Coliseum in Evansville, Indiana, along with Red Saunders and Stuff Smith.

On May 11, 1948, they were part of a big benefit, held at the Warner Theater in Atlantic City, for "crippled kiddies". The star was Al Jolson; the Red Caps were also there. On June 17, they were back at Atlantic City's Club Harlem (with Butterbeans & Susie) for the opening of the club's season. Once again, they were there for the whole summer.

On May 11, 1948, they were part of a big benefit, held at the Warner Theater in Atlantic City, for "crippled kiddies". The star was Al Jolson; the Red Caps were also there. On June 17, they were back at Atlantic City's Club Harlem (with Butterbeans & Susie) for the opening of the club's season. Once again, they were there for the whole summer.

An article in the September 18, 1948 Pittsburgh Courier talked about the death of Bethel "Gip" Gibson (of the comedy dance team Mitchell & Gibson) in Harmon (upstate New York). Remember, this is Duke Gibson, last seen with the Chocs in 1942. He was en route to Chicago for an engagement, when he got into a fight with a conductor and was put off the train. He was later found dead in the Hudson River. The article said that one of the brothers (unnamed, but it was Albert) was currently with the Chocolateers at the Club Harlem. The coroner's eventual verdict was foul play, but I don't know any further details. However, that blurb was the only time that his two names were juxtaposed: he was referred to as "Duke Bethel Gibson". (Father Bethel Gibson, Sr., head of the "famous Gibson family", had died in 1945.) This how it was reported in the September 25 Afro-American:

An article in the September 18, 1948 Pittsburgh Courier talked about the death of Bethel "Gip" Gibson (of the comedy dance team Mitchell & Gibson) in Harmon (upstate New York). Remember, this is Duke Gibson, last seen with the Chocs in 1942. He was en route to Chicago for an engagement, when he got into a fight with a conductor and was put off the train. He was later found dead in the Hudson River. The article said that one of the brothers (unnamed, but it was Albert) was currently with the Chocolateers at the Club Harlem. The coroner's eventual verdict was foul play, but I don't know any further details. However, that blurb was the only time that his two names were juxtaposed: he was referred to as "Duke Bethel Gibson". (Father Bethel Gibson, Sr., head of the "famous Gibson family", had died in 1945.) This how it was reported in the September 25 Afro-American:

Funeral services for Bethel Gibson, 25-year-old dancer, were held here Friday, a week after his body was found floating in the Croton River in up- State New York at Harmon.

Rites were held at the Ethel Milner funeral parlor, 130th St. and Lenox Ave. Survivors are brother, Albert, member of the Chocolateers, and a sister, Dixie, who was last heard from in Calif.

Mystery shrouds the circumstances leading up from the time Gibson was ejected from a Chicago-bound train by the conductor, until his body, clothed only in socks and shorts, was washed up from the river.

It is said by the Nat Nazarro office that Gibson and his partner, Kenneth Mitchell, boarded the train Tuesday night for Chicago, to open an engagement at the Beige Room of the Pershing Hotel.

Gibson, it has been reported, missed his wallet, containing his ticket and became enraged and abusive which led to his leaving the train.

The Nazarro office reports that Gibson called the office secretary, Miss Mary Quinton, about 2:00 a.m Wednesday at her home, telling her of the incident, and that he did not have enough money to proceed to Chicago.

Advised to return to New York City and get additional funds, nothing more was heard from him.

Meanwhile, Mitchell called from Chicago asking Gibson's whereabouts as he did not show up for the engagement. Then Harmon police were asked to investigate at the point where Gibson left the train.

The dancer's coat, sports jacket and shoes were found several hundred yards from where his body was found floating.

October 1948 saw them at the Broadway Theater (Kingston, New York). They were advertised as "of the Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington stage shows". Then, it was back to the Apollo, the week of November 5, along with Joe Liggins & Honeydrippers and the Luis Russell orchestra. They closed out the year at the Club DeLisa in Chicago.

They were back at the Apollo Theater the week beginning April 1, 1949. Other acts were Amos Milburn and Chubby Jackson.

And then, the really Big Time: The Palladium in London. I can find the record of them (Paul Black, Albert Gibson, and Eddie West) sailing to England, arriving on April 20, 1949. The May 14 review said that they called themselves "Harlem's Ambassadors Of Fun" and that the act went over well. (There was someone named Danny Kaye along, but he doesn't seem to have been a member of the Chocolateers.) Actually, since the King and Queen came to see Kaye, they would have seen the Chocs too. Not a bad audience. On June 7, they were at the Nottingham Empire, sharing the stage with Dorothy Cooke's Pony Revue. After that, it was the Hippodrome in Birmingham.

And then, the really Big Time: The Palladium in London. I can find the record of them (Paul Black, Albert Gibson, and Eddie West) sailing to England, arriving on April 20, 1949. The May 14 review said that they called themselves "Harlem's Ambassadors Of Fun" and that the act went over well. (There was someone named Danny Kaye along, but he doesn't seem to have been a member of the Chocolateers.) Actually, since the King and Queen came to see Kaye, they would have seen the Chocs too. Not a bad audience. On June 7, they were at the Nottingham Empire, sharing the stage with Dorothy Cooke's Pony Revue. After that, it was the Hippodrome in Birmingham.

Sailing from England on June 22, they were back in time for a July 25 Vaudeville show at Loew's National, in Brooklyn. From there, they went to the Oriental Theater, in Chicago, opening on August 4, with Kitty Kalen and George Jessel. The reviewer said: "garbed in wild-colored suits" and "maximum showmanship and enthusiasm", although he might have been talking about Jessel. September 8 found them at the Palace Theater in New York, where they were the closing act (that is, the headliners; they beat out Ray Eberle for that honor). The reviewer called them "fast, funny and furious". After this, it was the Oriental Theater in Chicago and the National Theater in Louisville, Kentucky.

Sailing from England on June 22, they were back in time for a July 25 Vaudeville show at Loew's National, in Brooklyn. From there, they went to the Oriental Theater, in Chicago, opening on August 4, with Kitty Kalen and George Jessel. The reviewer said: "garbed in wild-colored suits" and "maximum showmanship and enthusiasm", although he might have been talking about Jessel. September 8 found them at the Palace Theater in New York, where they were the closing act (that is, the headliners; they beat out Ray Eberle for that honor). The reviewer called them "fast, funny and furious". After this, it was the Oriental Theater in Chicago and the National Theater in Louisville, Kentucky.

They were at the Apollo again the week of September 16, 1949. This time, they shared the stage with Roy Milton, Camille Howard, and the Trumpeteers.

Another big time appearance. On September 27, they were guests on the third episode of "Sugar Hill Times" (with Thelma Carpenter and the Charioteers). This was the first regularly-scheduled prime time network television series with an all-black cast (although the 3 Flames and the Southernaires Quartet also had shows around then). The hosts of this hour-long CBS show were Willie Bryant, Harry Belafonte, and Timmie Rogers. Unfortunately, the first three episodes, including theirs, aired on Tuesday evenings from 8-9 PM, directly opposite Milton Berle, the one show almost everyone in the country was watching. Although it was cut back to a half hour and moved to Thursday night, the damage was done. The show only ran for five episodes.

In late October, they played the Earle Theater, in Philadelphia, with the Ravens, Dinah Washington, and Dizzy Gillespie's band.

A sad day for the dancing community: Bill "Bojangles" Robinson died on November 25, 1949. Seven days later, a group of 21 (mostly) tap dancers formed a society called the Copasetics in his memory. Two of the original members were Chocolateers: Paul Black and Eddie West; Albert Gibson subsequently became a member. Other originals you might know were Honi Coles, Cholly Atkins, and Peg Leg Bates. For years, they put on shows and promoted tap dancing. Ernest Brown, the last surviving original member, died in 2009.

A sad day for the dancing community: Bill "Bojangles" Robinson died on November 25, 1949. Seven days later, a group of 21 (mostly) tap dancers formed a society called the Copasetics in his memory. Two of the original members were Chocolateers: Paul Black and Eddie West; Albert Gibson subsequently became a member. Other originals you might know were Honi Coles, Cholly Atkins, and Peg Leg Bates. For years, they put on shows and promoted tap dancing. Ernest Brown, the last surviving original member, died in 2009.

On February 3, 1950, the Chocs began a week at the Regal Theater in Chicago, along with the Ravens, Dinah Washington, and the Joe Thomas Orchestra; they'd all just finished up at the Paradise in Detroit. Then, it was back to the Apollo on February 24. along with the Ink Spots and Bull Moose Jackson. In late March, they played the Strand, on Broadway, sharing the boards with Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and the Will Mastin Trio.

On February 3, 1950, the Chocs began a week at the Regal Theater in Chicago, along with the Ravens, Dinah Washington, and the Joe Thomas Orchestra; they'd all just finished up at the Paradise in Detroit. Then, it was back to the Apollo on February 24. along with the Ink Spots and Bull Moose Jackson. In late March, they played the Strand, on Broadway, sharing the boards with Billie Holiday, Count Basie, and the Will Mastin Trio.

On June 15, they opened at Club Harlem in Atlantic City as part of Larry Steele's "Smart Affairs of 1950" revue. It also starred Billy Daniels, George Kirby, and Lester Goodman's Octopus Dancers (don't ask). The Chocs did what one reviewer referred to as "comedy mugging and eccentric dance routines". This was a summer-long engagement.

On June 15, they opened at Club Harlem in Atlantic City as part of Larry Steele's "Smart Affairs of 1950" revue. It also starred Billy Daniels, George Kirby, and Lester Goodman's Octopus Dancers (don't ask). The Chocs did what one reviewer referred to as "comedy mugging and eccentric dance routines". This was a summer-long engagement.

In late September, they were at Bop City on Broadway, in a revue called "Jazz Train". It also featured Fletcher Henderson's band, Dotty Saulter, Rose Hardaway, and Red Allen. Between shows (there were three hour-long shows a night), Earl Bostic's band played bop and jazz. While the show did well, Bop City didn't, closing in October. However, it was quickly purchased, renamed the Paradise Club, and the revue continued, adding Harry Belafonte to the cast.

It was back to the Apollo on December 7, along with Ruth Brown, Willis Jackson, and Nipsey Russell. Apollo owner Frank Schiffman's comment: "Did cafe scene. Repeat, but very funny." From December 23-31, they were booked into St. Louis' Club Riviera, along with Anna Winburn's Sweethearts and Son & Sonny.

On February 8, 1951, they opened at the Palace Theater. The review said that they'd replaced their "cafe-drunk-waiter routine" (which they'd later record as "Bartender Blues").

In May, they were part of the "1951 Swing Parade" tour with Helen Humes, Jimmy Witherspoon, and the Hal Singer Orchestra. It started in Cincinnati on May 4.

Back to the Apollo on November 16, this time with the Ravens and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson. This time, Frank Schiffman said: "Repeated cafe scene. This has been overdone and must not repeat. Although still very active, very good, and very funny." Make up your mind, Frank.

When the Chocs appeared with Tony Martin at the Fox in Chicago, Ziggy Johnson (in the Chicago Defender of February 23, 1952) called them "a combination of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Red Skelton, Patterson and Jackson, [and] Milton Berle."

On April 12, 1952, the 3 Chocolateers became part of the "Biggest Show Of 1952" with Patti Page, Frankie Laine, Illinois Jacquet, and the Billy May orchestra. One reviewer described them as "three acrobatic clowns". It began in Washington, D.C. on April 12, moving on to Richmond, C.Y.C. (Scranton, Pennsylvania) on the 17th, the Hershey Sports Arena (Hershey, Pennsylvania) on the 18th, the War Memorial Theater (Syracuse, New York) on the 23rd, the Syria Mosque (Pittsburgh) on April 25 and The Auditorium (Milwaukee) on May 8. It concluded at the Stadium (Chicago) on May 10.

On April 12, 1952, the 3 Chocolateers became part of the "Biggest Show Of 1952" with Patti Page, Frankie Laine, Illinois Jacquet, and the Billy May orchestra. One reviewer described them as "three acrobatic clowns". It began in Washington, D.C. on April 12, moving on to Richmond, C.Y.C. (Scranton, Pennsylvania) on the 17th, the Hershey Sports Arena (Hershey, Pennsylvania) on the 18th, the War Memorial Theater (Syracuse, New York) on the 23rd, the Syria Mosque (Pittsburgh) on April 25 and The Auditorium (Milwaukee) on May 8. It concluded at the Stadium (Chicago) on May 10.

An ad that appeared in the May 3 1952 Billboard was for "Good Story Blues" and "Lady Ginger Snap", on Hi-Lo, by Chocolate Williams & His Chocolateers. This is not the Chocs; Williams was a bassist with Herbert Nichols' orchestra.

The guys were supposed to be part of the cast of the "Shuffle Along" revival that opened on Broadway on May 8. It's a good thing that they weren't; it closed on May 10.

After this, they played the Palace Theater again. The reviewer was unimpressed: "... Three Chocolateers who, as far as this reporter is concerned, can toss overboard three-quarters of their screaming, knockabout comedy and stick to eccentric stepping." In August they were at LaRue's Supper Club in Indianapolis.

After this, they played the Palace Theater again. The reviewer was unimpressed: "... Three Chocolateers who, as far as this reporter is concerned, can toss overboard three-quarters of their screaming, knockabout comedy and stick to eccentric stepping." In August they were at LaRue's Supper Club in Indianapolis.

June 26, 1952 found them back at the Club Harlem in Atlantic City, part of Larry Steele's "Smart Affairs Of '53" revue. Others in the cast were Peg Leg Bates, the 4 Tunes, and Olivette Miller (swing harpist). The show ran through September 7.

The Chocs were back at the Apollo on September 19, 1952, along with the 5 Keys, Jimmy Forrest, the Fontaine Brothers, and Olivette Miller "jazz harpist" (a real harp, not a harmonica). [This time Apollo's Frank Schiffman said: "Did cafe scene. Getting worn too thin."] Olivette was the daughter of Flournoy Miller (who, way back when, had written the musical "Runnin' Wild", which had introduced the Charlston). This is not just one of the random facts I load down these articles with; a gossip column said that she was going to divorce her husband and take up with Al Gibson of the Chocolateers. The gossip was true for a change: by 1954, they were married.

The Chocs were back at the Apollo on September 19, 1952, along with the 5 Keys, Jimmy Forrest, the Fontaine Brothers, and Olivette Miller "jazz harpist" (a real harp, not a harmonica). [This time Apollo's Frank Schiffman said: "Did cafe scene. Getting worn too thin."] Olivette was the daughter of Flournoy Miller (who, way back when, had written the musical "Runnin' Wild", which had introduced the Charlston). This is not just one of the random facts I load down these articles with; a gossip column said that she was going to divorce her husband and take up with Al Gibson of the Chocolateers. The gossip was true for a change: by 1954, they were married.

From October 10-13, they were back with Larry Steele's "Smart Affairs Of '53" at the Capitol Theater in Detroit.

In late January 1953, they spent a week at the Seville Theater in Montreal, sharing the stage with Louis Armstrong and Velma Middleton. In March, the Chocs were part of Larry Steele's latest "Smart Affairs" revue, playing at Miami's Riviera Club. The cast of 40 included Olivette Miller.

In early May 1953 (exact date unknown), the 3 Chocolateers did something that, as far as I know, they'd never done before and would never do again: they made some non-video recordings. They were appearing at the Club DeLisa in Chicago and consented to record four sides for Al Benson's Parrot label with the Red Saunders band: "Bartender Blues", "Peckin'", "Waitin' For Jane", and "Little Willie". "Bartender Blues" is the "cafe-drunk-waiter" routine previously mentioned. For me, it works (although it was probably much funnier as a visual routine), but I can't imagine them recording much of their act.

In early May 1953 (exact date unknown), the 3 Chocolateers did something that, as far as I know, they'd never done before and would never do again: they made some non-video recordings. They were appearing at the Club DeLisa in Chicago and consented to record four sides for Al Benson's Parrot label with the Red Saunders band: "Bartender Blues", "Peckin'", "Waitin' For Jane", and "Little Willie". "Bartender Blues" is the "cafe-drunk-waiter" routine previously mentioned. For me, it works (although it was probably much funnier as a visual routine), but I can't imagine them recording much of their act.

It's something of a mystery who "Little Willie" was, since he's prominently mentioned in "Bartender Blues" and, presumably, the eponymous "Little Willie" of the unreleased track. I can't find any records of someone nicknamed "Little Willie" ever being with them. A small blurb in the New York Age (May 23, 1953) mentioned that "Bill Hurd, formerly of the famed Chocolateers, rocked Dorsey's Mother's Day crowd." (The only entertainer named Bill Hurd I can find is a singer who was popular in Troy, New York from 1946 to 1951; a 1951 ad says "formerly of Cab Calloway's Orchestra".) But if this is "Little Willie", he would have had to have left the group immediately after the recording session, since Mother's Day was on May 17 in 1953. Therefore, I'm betting that Hurd was not "Little Willie". A better guess (and that's all it is) is that "Little Willie" was just the name of a character in their act (possibly played by Eddie West, since he was short). There's no evidence that the recordings were by anyone other than Paul Black, Albert Gibson, and Eddie West.

It's something of a mystery who "Little Willie" was, since he's prominently mentioned in "Bartender Blues" and, presumably, the eponymous "Little Willie" of the unreleased track. I can't find any records of someone nicknamed "Little Willie" ever being with them. A small blurb in the New York Age (May 23, 1953) mentioned that "Bill Hurd, formerly of the famed Chocolateers, rocked Dorsey's Mother's Day crowd." (The only entertainer named Bill Hurd I can find is a singer who was popular in Troy, New York from 1946 to 1951; a 1951 ad says "formerly of Cab Calloway's Orchestra".) But if this is "Little Willie", he would have had to have left the group immediately after the recording session, since Mother's Day was on May 17 in 1953. Therefore, I'm betting that Hurd was not "Little Willie". A better guess (and that's all it is) is that "Little Willie" was just the name of a character in their act (possibly played by Eddie West, since he was short). There's no evidence that the recordings were by anyone other than Paul Black, Albert Gibson, and Eddie West.

"Peckin'" and "Bartender Blues" (by the "Chocolateers") were released, on Parrot, in July 1953, although they were never reviewed. The Parrot ad referred to the song as "Bartenders' Ball".

"Peckin'" and "Bartender Blues" (by the "Chocolateers") were released, on Parrot, in July 1953, although they were never reviewed. The Parrot ad referred to the song as "Bartenders' Ball".

In August, they played LaRue's Supper Club in Indianapolis. They were back in Chicago in September as part of the "Slap-Happy Daze" show at the Club DeLisa. On October 13, they were part of the Artists Society Of America "Cavalcade Of Celebrities" at Chicago's Blue Note. Others appearing were Dizzy Gillespie, Eartha Kitt, Robert Clary, and that up-and-coming group, the Flamingos.

In August, they played LaRue's Supper Club in Indianapolis. They were back in Chicago in September as part of the "Slap-Happy Daze" show at the Club DeLisa. On October 13, they were part of the Artists Society Of America "Cavalcade Of Celebrities" at Chicago's Blue Note. Others appearing were Dizzy Gillespie, Eartha Kitt, Robert Clary, and that up-and-coming group, the Flamingos.

Then it was off to New York for an October 16 appearance at the Apollo, along with Wynonie Harris, Varetta Dillard, the Frank "Fat Man" Humphries orchestra, and Bunny Briggs. They didn't make a hit with Schiffman: "Did rather short comedy dance act with a minimum of talk. Quite disappointing. Act has long been overpaid by us." What a cheapskate! Since the first time Schiffman started keeping notes on them (April 22, 1948), he'd paid them $750 for the week.

Then it was off to New York for an October 16 appearance at the Apollo, along with Wynonie Harris, Varetta Dillard, the Frank "Fat Man" Humphries orchestra, and Bunny Briggs. They didn't make a hit with Schiffman: "Did rather short comedy dance act with a minimum of talk. Quite disappointing. Act has long been overpaid by us." What a cheapskate! Since the first time Schiffman started keeping notes on them (April 22, 1948), he'd paid them $750 for the week.

The November 26, 1953 Jet reported that the 3 Chocolateers had broken up when Olivette Miller pulled Albert Gibson out of the act (to form, reasonably enough, "Miller & Gibson"). However, in the December 10 Jet, Gibson said that the real reason for him leaving was that they weren't getting the money that the act deserved. Far from having broken up, Paul Black and Eddie West replaced Gibson with James "Chuckles" Walker, who had been part of Chuck & Chuckles and Myers & Walker ("Two Dark Spots Of Joy - song, dance and xylophone").